[American Fishes: a popular treatise upon the game and food fishes of North America with especial reference to habits and methods of capture. by G. Brown Goode; public domain]

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”1

Since “The Bait” is a parody of Christopher Marlowe’s poem “Come Live with Me and Be my Love” (1599), we’ll begin with that poem:

Come live with me and be my love,

And we will all the pleasures prove,

That Valleys, groves, hills, and fields,

Woods, or steepy mountain yields.

And we will sit upon the Rocks,

Seeing the Shepherds feed their flocks,

By shallow Rivers to whose falls

Melodious birds sing Madrigals.

And I will make thee beds of Roses

And a thousand fragrant posies,

A cap of flowers, and a kirtle

Embroidered all with leaves of Myrtle;

A gown made of the finest wool

Which from our pretty Lambs we pull;

Fair lined slippers for the cold,

With buckles of the purest gold;

A belt of straw and Ivy buds,

With Coral clasps and Amber studs:

And if these pleasures may thee move,

Come live with me, and be my love.

The Shepherds’ Swains shall dance and sing

For thy delight each May-morning:

If these delights thy mind may move,

Then live with me, and be my love.

Recall that Marlowe was a contemporary of Shakespeare (and that we spent some weeks here at The Priory on his magnificent play Dr. Faustus). Marlowe’s poem is the quintessential Renaissance poem in many ways, drawing heavily upon the pastoral tradition. This tradition idealizes the imagined idyllic life of the shepherd/poet/lover, who lounges about in tranquil fields (“pastor” is derived from “pasture”), watching over the sheep, playing music (or composing poetry), and wooing women. There’s not much more than this going on in Marlowe’s poem—he simply captures beautifully, fetchingly, and memorably a tradition that has been influential in art and literature for all time. More could be said about this poem were we not gathered here today to discuss Donne’s version.

Here is Donne, writing about a century later, in answer to Marlowe:

Come live with me, and be my love,

And we will some new pleasures prove

Of golden sands, and crystal brooks,

With silken lines, and silver hooks.

There will the river whispering run

Warm'd by thy eyes, more than the sun;

And there the 'enamour'd fish will stay,

Begging themselves they may betray.

When thou wilt swim in that live bath,

Each fish, which every channel hath,

Will amorously to thee swim,

Gladder to catch thee, than thou him.

If thou, to be so seen, be'st loth,

By sun or moon, thou dark'nest both,

And if myself have leave to see,

I need not their light having thee.

Let others freeze with angling reeds,

And cut their legs with shells and weeds,

Or treacherously poor fish beset,

With strangling snare, or windowy net.

Let coarse bold hands from slimy nest

The bedded fish in banks out-wrest;

Or curious traitors, sleeve-silk flies,

Bewitch poor fishes' wand'ring eyes.

For thee, thou need'st no such deceit,

For thou thyself art thine own bait:

That fish, that is not catch'd thereby,

Alas, is wiser far than I.

In and of itself, “The Bait” has more riches than can be mined in just one post, and added to these riches is the separate topic of the poem’s relationship to Marlowe’s poem. Thus, we will merely be able to skim the surface of the deep and lovely waters of these things.

First, let’s briefly examine how Donne is responding to Marlowe’s famous poem. Both poems share the same meter—iambic tetrameter (short stress followed by long in four feet, for a total of eight beats per line)—and use the same rhyme scheme. Donne’s poem is longer by a stanza, bringing the number to seven—an odd number but one with divine significance.

Both poems feature a lover wooing a beloved, but the first obvious difference is that Donne’s poem promises “some new pleasures” rather than “all the pleasures” that the traditional pastoral world can yield. “Some” vs. “all” strikes a more modest note, yet “new” offers something more daring. Marlowe’s speaker confidently offers the woman all clichéd pleasures of the pastoral scene: hills, groves, mountains, valleys, birds, birdsongs, shepherds, flocks, floral crowns. (It sounds too good to be true, doesn’t it? And it is.)

By echoing Marlowe from the start, then shifting to imagery that is as far from the pasture as the right is from the left—from fields to rivers, brooks, fish, and swimming—Donne’s poem startles and surprises the knowing reader. Moreover, rather than bare, brute nature, the speaker in Donne’s poem bathes the opening images in things of constructed human value: gold, crystal, silk, and silver.

So the first thing Donne is doing in “The Bait” is disrupting the poetic tradition and upending expectations.

The second thing he does to depart from Marlowe is to speak more of his subject than himself. Marlowe’s poem is mostly about all the things the speaker will offer the one he woos. The speaker in Donne’s poem, on the other hand, is so enraptured by the woman that he waxes mainly about her. Her eyes warm the river. She draws all the fish to her. Her light is so bright that it outshines both the sun and the moon. While other fishers need nets, snares, and flies to catch their fish, she “needs no such deceit.” She is her own bait, and she has caught him—which reverses the dynamic in Marlowe’s poem where the speaker tries to catch the woman.

There is an eroticism, too, that underlies much of the poem. The fish are “enamored” and “amorous.” The image of a beautiful woman swimming is, of course, inherently sensual. Numerous words throughout accumulate toward erotic suggestiveness: “eyes,” “hands,” “catch,” “bedded,” “silken,” and “wandering eyes.” Marlowe’s poem sings. Donne’s sizzles.

On the most “literal” reading of the poem, the beloved is “the bait” that catches fish and the lover by her beauty, light, and truthfulness. But again, Donne is not Marlowe. Donne is a metaphysical poet, and his conceit here is more than meets the eye.

The “bait” is the “thou” (the woman) being addressed throughout the poem. If Donne is using bait as a conceit—an extended metaphor that compares an earthly, material object to some spiritual or transcendent truth—then what might the poem be comparing to bait?

One reading some critics offer is that “The Bait” is really about Christ, that Christ is the bait. Christ is like a lovely woman who draws fish to her with beauty and without guile.

Christ is the One who—being God, too—is his own bait. Christ is the bait for all “fishers of men.” Christ is the one who draws the enamored fish with his body. Christ is the beauty who shimmers like sliver, crystal, and gold, who uses no snares, nets, or tricks to catch us. And to be so caught—we must, as the speaker suggests—be more willing to be taken than are the “wiser” fish who get away. To be caught by Christ we must become like children2—or like innocent, curious fish.

[Update: Readers, I cannot do numbers. At. All. Donne and Marlowe were contemporaries. Donne’s poem was published just decades after Marlowe’s. I don’t know why I always jump a century ahead. Sigh. I even double-checked the dates and somehow still messed it up! My apologies!}

Next week will, sadly, be our last week with Donne (for now—I may circle back next “school” year!). Next week’s poem: “Show Me Dear Christ, Thy Spouse So Bright and Clear”

Then I will reflect on the one-year (one-year!!!) anniversary of The Priory. Then we’ll continue my intermittent series on Platform, Publishing, and Perspective with some author interviews. I can’t wait to share those with you!

***

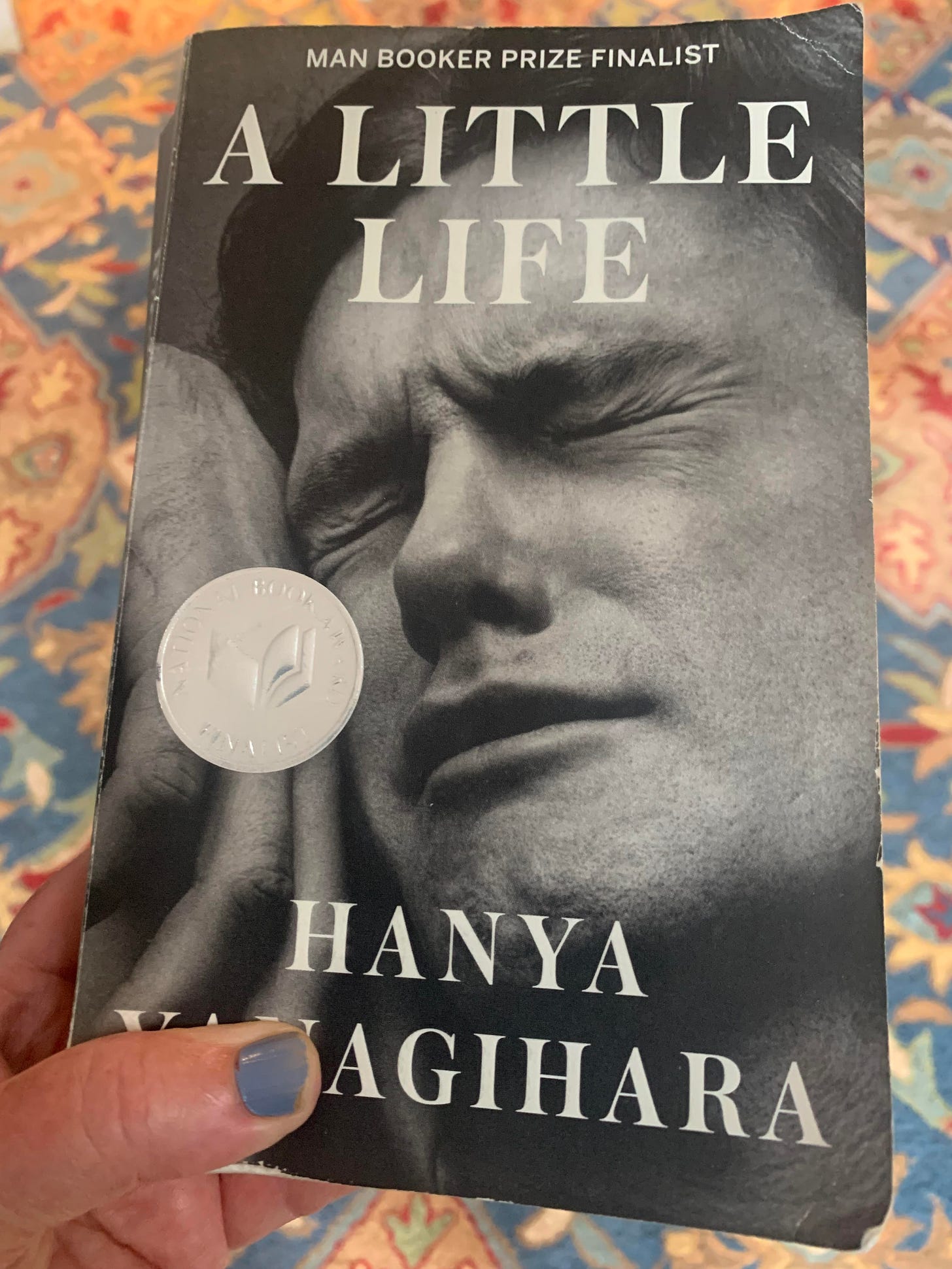

BOOK NOTE:

I am almost done reading one of the best novels I’ve read in years: A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara. (My apologies for inadvertently covering up her name in the photo.) I am not making a general recommendation of this book as it is not for the faint of heart. Its story contains physical and sexual abuse along with intense human pain and suffering. As anyone who knows me knows, however, I prefer dark, gritty books. This is definitely that. However, it is an astonishingly-told story, beautiful and penetrating in characterization, conception, and writing. It’s been a long time since I’ve been compelled to read all day and into the night to keep turning the pages. But, again, this is likely not a book for everyone. It is stunning.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

Marlowe's poem is solidly in the pastoral tradition. Donne's clever satire is both sharp - love the stanza about letting others cut themselves on oyster shells - and seductive.

Karen and Jack, I was raised on classical music and so knew little to nothing about the Police, until the classical music station we listened to started talking about an album released by Police lead singer Sting. Called Songs from the Labyrinth, it was songs by Renaissance lutenist and composer John Dowland, who was contemporary with Shakespeare. Sting's roughened rockstar voice (the rock style can really damage a voice if it isn't trained well) goes a bit oddly with the refined Renaissance phraseology but I think the classical world was just delighted to be noticed: https://youtu.be/RYb-7JOQRQQ?feature=shared

The Marlowe poem became instantly famous. Sir Walter Raleigh and Izaak Walton also wrote poems inspired by it. And if anyone thinks it sounds mildly Shakespeare, the poem was set to music in the 1995 film of Richard III. A person can probably find a clip of that segment online.

I tend to read "The Bait" less about Christ. I question myself on how far to separate Donne's erotic poems from his religious poems--sometimes they are identical--but "The Bait" seems more one than the other.

I agree about the Police, but now my quibble with them: "Don't Stand So Close to Me" is Exhibit A on how not to do an allusion. The lyric about "the famous book by Nabokov" is very annoying.