The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus: Week 1

"This the man that in his study sits"

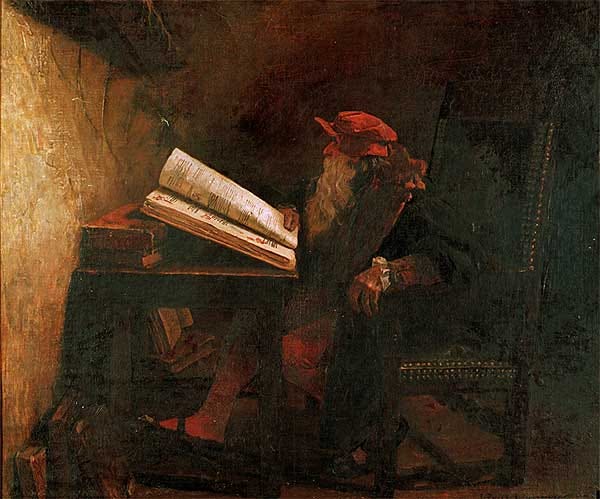

[Dr. Fausto by Jean-Paul Laurens: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jean_Paul_Laurens_-_Dr._Fausto.jpg]

(Welcome, new subscribers! I’m so glad you’re here! At The Priory, I mainly try to focus my (and our) attention on the good, true and beautiful. Presently, I am doing so through a survey of British literature of sorts—peppered now and then with posts offering thoughts on life, writing, culture, and the things that get me fired up. You can read about how I got here here. My posts are free for all to read, but comments are usually open only to paid subscribers. That’s mainly a way to protect myself from trolls, but also a way to build a little community of support in a time when many of us need that. I hope you will consider becoming a paid subscriber if you can. There is a group discount available for two or more subscribers. But I’m also happy to give you a paid subscription if you can’t pay right now. Just email me at karenswallowprior (at) gmail and let me know.)

***

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.” – Simone Weil1

Christopher Marlowe was born in 1564, as was his fellow playwright William Shakespeare. While the two were contemporaries within the London theater scene, there isn’t evidence of a personal friendship between them, although Shakespeare (and other playwrights) were clearly influenced by Marlowe’s work, as Marlowe got the earlier start in writing for the stage.2 But Marlowe’s life was short. He was killed under mysterious circumstances (theories and accounts abound) in 1593 while awaiting an appearance before the Privy Council following his arrest on charges related to libel and heresy. His life was short, but quite dramatic. Marlowe was accused of being many things, most of which cannot be known for certain, including spy, atheist, and homosexual. Suffice it to say that the politics of the day were complicated, deadly, even. As a result, Marlowe’s body of work, though impressive and significant, was foreshortened by his death at such a young age.

The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus is often considered the first English tragedy. Written in 1592 or 1593, it was published, posthumously, in 1604. Confusingly, there are two versions, the A Text and the later B Text which is longer, containing additions and alterations made by Marlowe’s contemporaries and which may reflect some of his own revisions. The Dover edition I am using is the A Text.

Even if you’ve never read this play before, you are likely already familiar with the idea of “selling your soul to the devil,” a theme found across ages and art forms. You may even know the term “Faustian bargain,” which alludes to this legend to refer to the trap of making a deal in which one thinks one is gaining something great … but actually losing much, much more.

The central theme of the play is not Marlowe’s original creation, but one rooted in myth, legend, and various tellings. The play is likely based on an English translation of a German account of a certain Johann Faust (c. 1480–1540), an actual person who dabbled in astrology, magic, and alchemy, and who became the stuff of legends.3 Some accounts of this Faust treat the events and person as factual, based on alleged eyewitness accounts of his demise. Marlowe, however, is clearly treating the story imaginatively, taking a fascinating, pre-existing story and molding it into a magnificent work of art that engages with some of the most monumental questions emerging at this particular historical moment as well as those of the universal human condition that transcend time.

In reflecting his own age—the Renaissance—Marlowe paints a picture of a man with one foot in the age that is passing and one in the revolutionary new one to come. Medieval meets modern in this play.

From the temptation plot to the presence of the Good Angel and the Evil Angel, from the pageant of the Seven Deadly Sins to the entance of the Pope himself, the play is laden with the presence of the medieval church and many of the tropes found within medieval morality plays.

At the same time, the play is wonderfully reflective of the Renaissance’s rebirth of classical art and ideals. These include the genre of tragedy itself, as Dr. Faustus echoes the narrative arc of classical tragedy, along with the portrayal of characters ripped from the pages of classical literature and myth. The Chorus, which opens and closes the play, is another particular feature taken from classical drama. One role the Chorus serves in both contexts is to aid us in interpretation by telling us what is happening and what it means. Further, as in classical tragedy, Faustus is a hero who is obviously flawed but also admirable, a complexity we will examine more closely in a later post. Even the way Faustus seems overcome by fate (albeit in the Christian form of Lucifer) echoes the classical sense of the tragic which portrays a tragic fall as one that results from the combined forces of fate and the hero’s flaw.

Despite all of these classical and medieval traces, Marlowe paints in Faustus a picture of a modern man, a man so modern, I think it’s safe to say, most of us could see ourselves in him without squinting too much. More about that later, too.

One more thing I want to say before diving in is that the structure of the play is important and ingenious.

Here is what happens: the play consists of fourteen scenes. In the first half of the play, the scenes alternate back and forth between very serious and foreboding scenes and scenes depicting silly shenanigans by low, comic characters. There is more going here in these scenes than mere comic relief, however. As you read, pay attention to two things. First, notice how these alternating comic scenes parody the scene that came before. Second, as the play continues, notice how that order gets mixed up as slowly the comic and the serious overlap and then blur as the tragic figure gets more ridiculous and the consequences of his folly aren’t just being mirrored by others but manifest in his own life.

Now, let’s dive in by looking at the prologue, spoken by the Chorus.

First, we are told what the play will not be about. And what it will not be about are the high and mighty warriors and kings of old:

CHORUS. Not marching now in fields of Thrasymene,

Where Mars did mate the Carthaginians;

Nor sporting in the dalliance of love,

In courts of kings where state is overturn’d;

Nor in the pomp of proud audacious deeds,

Intends our Muse to vaunt her heavenly verse:

Notice the Muse, a classical reference. These things mentioned above are not what will inspire the Muse of this work, but rather,

Only this, gentlemen,—we must perform

The form of Faustus’ fortunes, good or bad:

In other words, this play will be about Faustus, gentlemen (and ladies), who is a particular man in a particular place and particular time. (The focus on particularities is very much a modern development.) We next get a little bit of his history, and here is where things take another modern turn, because unlike the heroes of classical tragedy, Faustus is not noble or high born, but low born (base). Under the care of a relative, however, it is possible for him to go to school (at Wittenberg, which is very significant) where he is wildly successful:

To patient judgments we appeal our plaud,

And speak for Faustus in his infancy.

Now is he born, his parents base of stock,

In Germany, within a town call’d Rhodes:

Of riper years, to Wittenberg he went,

Whereas his kinsmen chiefly brought him up.

So soon he profits in divinity,

The fruitful plot of scholarism grac’d,

That shortly he was grac’d with doctor’s name,

Excelling all whose sweet delight disputes

In heavenly matters of theology;

But, the plot thickens. He excels only:

Till swoln with cunning, of a self-conceit,

His waxen wings did mount above his reach,

And, melting, heavens conspir’d his overthrow;

Notice the classical reference to Icarus, flying too close to the sun:

For, falling to a devilish exercise,

And glutted now with learning’s golden gifts,

He surfeits upon cursed necromancy;

Nothing so sweet as magic is to him,

Which he prefers before his chiefest bliss:

And this the man that in his study sits.

Our “chiefest bliss” refers to love of God. Faustus, the Chorus tells us, chooses the dark arts over God.

Now the scene is set. We are introduced to the man and to the play that is about to begin. Here he sits in his study. Next week we will explore what he is doing there.

***

Here’s my upcoming speaking schedule in case you are near where I will be in coming days:

Chattanooga, TN: Wed. April 3, Southern Adventist University, 7 p.m.

Houston, TX: Thurs. April 11, Memorial Drive Presbyterian Church, 7 p.m.

Grand Rapids, MI: Fri-Sat. April 12-13, Calvin University, Festival of Faith and Writing (Full schedule here: https://ccfw.calvin.edu/festival-2024/plan-your-visit/festival-schedule/)

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

The film Shakespeare in Love (which takes a lot of poetic license throughout) features Marlowe in a couple of cameo scenes, as I remember. Here’s one:

Karen, I started reading this play over the weekend. I read the first three lines and thought, "I'm out!" Haha ;-). I ended up reading it and understanding the gist of the Chorus. Your explanation of Marlowe's history and breakdown of the chorus illuminated the passage for me. Thanks for taking the time to do that. I settled into the language and meter, plodded through some of the play, and have enjoyed it so far. It's been a while since I exercised that muscle in my brain. It's been 19 years since I was in Romeo and Juliet; I haven't picked up a play like that since. Btw, I played Juliet's mom (hahahahaha).

There is a 19th century opera, Faust, by the French composer Charles Gounod, with a libretto based on the German poet Goethe's play of the same name. Growing up both listening to and learning to play classical music, I early learned the basic story of Dr. Faustus. The local classical radio station frequently played this famous Waltz from the opera: https://youtu.be/kTvJbRa9alY?feature=shared

I also became familiar with the expression 'selling one's soul's for the same reason. The accusation of selling one's soul to the devil in exchange for benefits is one that has been repeatedly leveled at highly skilled musicians, from the 19th century virtuoso violinist Niccolo Paganini - it is now known that Paganini had the congenital condition of Marfan syndrome which gave him an unusually long fingers, resulting in technical displays impossible for the average violinist, myself included, to reach - to the 1930's blues musician Robert Leroy Johnson - a fictional version of Johnson appears in the Coen brothers' film 'O Brother Where Art Thou'. I have always suspected jealous rivals started the rumours to make themselves feel better as music can be a cut-throat industry (one reason I chose not to become a professional).