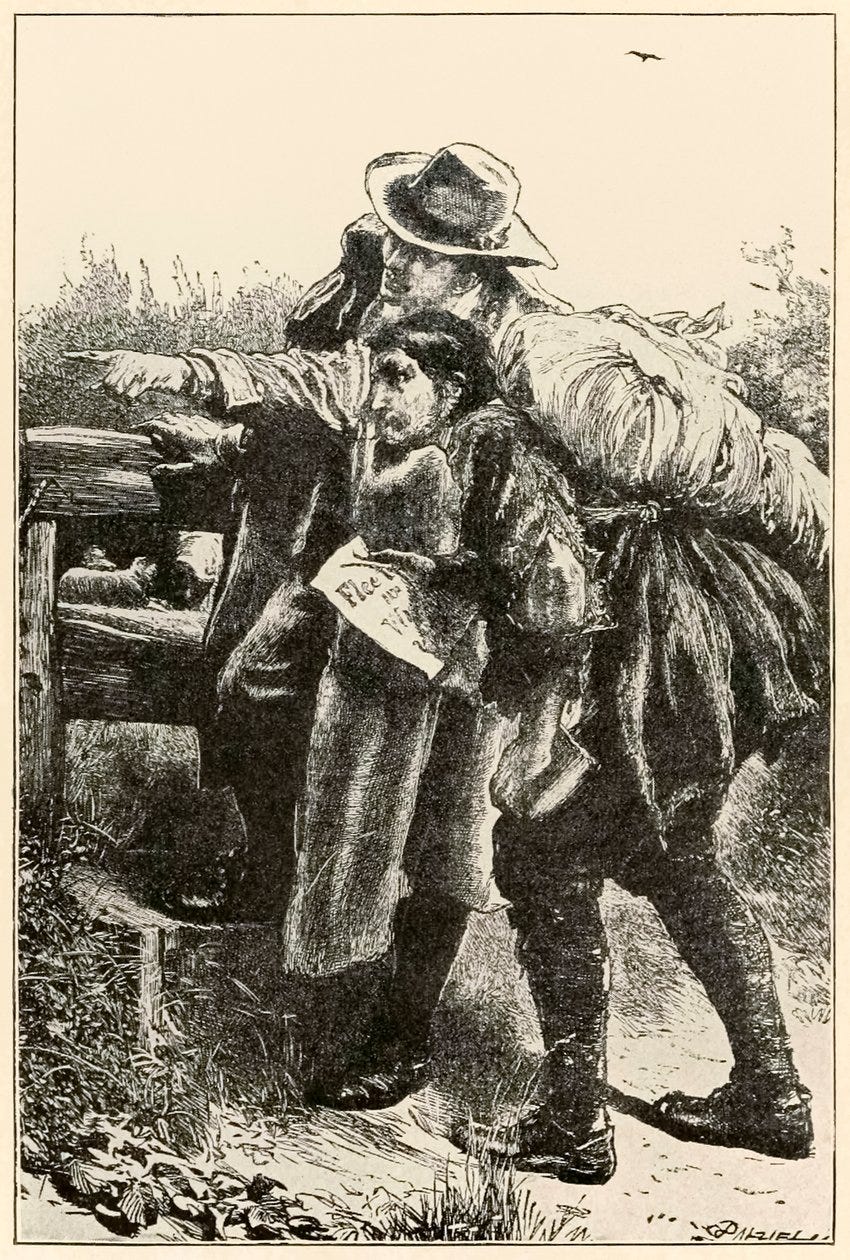

As I walked through the wilderness of this world, I lighted on a certain place where was a Den, and I laid me down in that place to sleep: and, as I slept, I dreamed a dream.1 I dreamed, and behold, I saw a man clothed with rags, standing in a certain place, with his face from his own house, a book in his hand, and a great burden upon his back. I looked, and saw him open the book, and read therein; and, as he read, he wept, and trembled; and, not being able longer to contain, he brake out with a lamentable cry, saying, "What shall I do?"

Is it any wonder that this opening—and the entire work—is so famous, so beloved, so memorable?

Let me talk about a few things that make it so.

First, The Pilgrim’s Progress has its place in the long and storied tradition of the dream vision. The dream vision is a literary genre in which some divine or spiritual knowledge is revealed in a dream and then retold. Dante’s Divine Comedy is a dream vision. Others in this tradition include The Dream of the Rood as well as “The Nun’s Priest’s Tale” from The Canterbury Tales. William Langland’s Piers Plowman is another medieval dream vision, and C. S. Lewis’s The Great Divorce and The Pilgrim’s Regress are modern examples. (Many works have allegorical elements without being full-blown allegories. Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels is one example. I think we might cover that here! It’s just around the corner from the late seventeenth century where we are now!)

It can be easy to lose track in a dream vision of the actual narrator of the story once immersed in that story. One of the things I love about how Bunyan tells his dream vision is that he intersperses frequent reminders of the presence of this dreamer who is telling us this dream. I’d invite you to think about the effect that has on the story Bunyan tells and why he does it.

The next thing about this opening that is reflected by the entire work is the style. The Pilgrim’s Progress is written in what is called the plain style. (Bet you can guess what that is!) The plain style, which prioritizes simplicity and clarity, was beloved by Puritans for both aesthetic and theological reasons. (It wasn’t used only by Puritans, however. It is also the favored style of classical orators such as Cicero and Seneca.) The Pilgrim’s Progress features ordinary words and uncomplicated sentences, but that doesn’t mean it is without art. It skillfully reflects the rhythm of natural speech but intentionally employs alliteration, repetition, parallelism, and the occasional dose of sardonic humor. Bunyan’s language is earthy and at times even gruesome. In so many ways, the language of Bunyan is the opposite of his contemporary John Milton.

And despite being an allegory, which emphasizes the symbolic and transcendent, The Pilgrim’s Progress is notable for its realism. It is characterized throughout by the particularity of its detail, its psychological depths, and for the sheer realness of its characters. This story is peopled not by ideal, ethereal, or romantic figures, but very realistic everyday folks as one would meet in our streets, workplaces, and neighborhoods today (and, I daresay, our churches!).

Most if not all of this is reflected in the opening passage but grows even more into this as we read along. So let’s do that now.

Christian is a kind of Everyman. In the century or two in between Everyman and The Pilgrim’s Progress emerged the “secular age” described by Charles Taylor (in his book of that title). What he means by that (and fleshes out in about 900 pages!) is the difference between a time when religious belief was assumed and a time when it was something one had to choose or decide upon (this is a greatly watered down version!). Thus, the anonymous author of Everyman could assume that “every man” knew he would someday meet his Maker and need to make an account. His story is not of the decision but of the accounting. Bunyan, in contrast, expresses in Christian the weight of modernity, that is the weight of choosing (or not choosing) to heed Evangelist, put his fingers in his ears to drown out the sounds of the world, go through the Wicket Gate, and persevere all the way to the Celestial City. The existential weight is all through The Pilgrim’s Progress. Everywhere. All the way.

Thus The Pilgrim’s Progress reflects a pivotal moment in history: the shift into modernity and all the agency that entails.

But Bunyan wasn’t likely thinking about that. What he is thinking about is his own theological convictions. And agree with them or disagree, there is no doubt that Bunyan brings incisive theological, spiritual, and psychological (before that was a thing) insights into the story.

Take Mr. Worldly-Wiseman. If we were today, in the year of our Lord 2025, to think of someone we might describe as “worldly wise,” I doubt we’d think of the worldview Bunyan offers in this character. Mr. Worldly-Wiseman isn’t someone who turns to new philosophies or material possessions in pursuit of the good life. No, he turns to morality. We think of “worldliness” today as being characterized by immorality. But Bunyan—with more astute precision than most of us have—understands that even our own morality, our own civility or adherence to the law is ultimately a worldly system, one based on a human kingdom rather than the kingdom of God. The symbols in this section are so varied and rich! And Bunyan makes sure that we understand their spiritual meaning through his glosses (those notes he provides in the margins) that point us to the biblical texts from which they are drawn.

We are wise to read with the advice offered by C.S. Lewis in last week’s post: explore the literal level of the symbol in order to better understand the spiritual one. When Christian sees the hill, he is physically afraid, afraid it will fall on his head. Contemplate that fear. If you have a fear of heights, you understand. I remember when I first moved to Virginia from a flat place, when I would drive into the Blue Ridge Mountains (which are more like hills, to be honest), I feared them at first! This is an example of the sublime: the large, magnificent sensory experiences that remind us of death. By thinking about the physical, material element of the allegory, we can deepen our understanding of the spiritual truth—in this case, the law is like a mountain that we ought to fear falling on us. And the world is filled with many Worldly-Wisemen who seem to want the same thing we want, who seem to be pointing us in the right direction, simply according to a better way. But it is a way that leads only to pain and perhaps death.

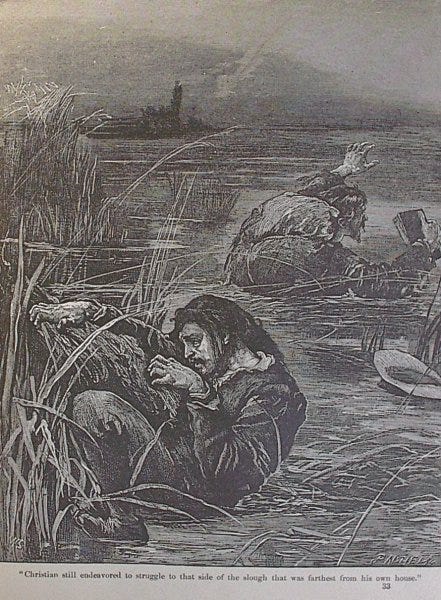

One line I love for its power and poetry comes from the passage on the Slow of Despond (or slough, depending on your edition2), describing the terrible state the travelers find themselves in. It is literally earthy in its language, powerful in its imagery, evocative in its symbolism, and poetic in its alliteration and consonance:

Here, therefore, they wallowed for a time, being grievously bedaubed with the dirt; and Christian, because of the burden that was on his back, began to sink in the mire.

I suppose it is challenging for most of us moderns to imagine a slow, bog, or miry pit in the terms that Christian does: of falling into it and being stuck in it. But most of us have at least seen some films or even episodes of Gilligan’s Island that can at least give us the idea of what such a quagmire might be like on the physical level. Most of us moderns have certainly experienced an emotional or spiritual state of despondency, so we have a sense of what that is like. And you have the blessing of John Bunyan to see that state for what it truly is like—quicksand. If you ever feel like you are in that kind of pit and you can’t get yourself out, Bunyan understands. And so does the Bible.

Speaking of the Bible, there is one more thing I must get to. (Already I am berating myself for trying to cover too much each week with this work!) This is the centrality of this entire story of reading, interpreting, and reading and interpreting more. The Bible is, of course, the text being read and interpreted and proclaimed—most notably by Evangelist and Interpreter. But this heavy emphasis on the written text is a hallmark of the seventeenth century (and beyond). This period marks the onset of print culture, a culture in which these activities were central, beginning with the Bible but eventually coming to include pamphlets (like Milton’s) and newspapers and eventually novels and so on. Even Christian’s continuing attempt to tell, remember, and retell his experiences as he progresses reflects an emphasis on interpretation and the importance of words (as well as the Word). Moreover, the writing and the reading of an allegory likewise emphasizes interpretation.

Correct interpretation is essential to understanding the gospel. Thus Interpreter tells Christian what the state of his house means:

Then [Interpreter] took [Christian] by the hand, and led him into a very large parlour that was full of dust, because never swept; the which after he had reviewed a little while, the Interpreter called for a man to sweep. Now, when he began to sweep, the dust began so abundantly to fly about, that Christian had almost therewith been choked. Then said the Interpreter to a damsel that stood by, Bring hither the water, and sprinkle the room; the which, when she had done, it was swept and cleansed with pleasure.

CHR. Then said Christian, What means this?

INTER. The Interpreter answered, This parlour is the heart of a man that was never sanctified by the sweet grace of the gospel; the dust is his original sin and inward corruptions, that have defiled the whole man. He that began to sweep at first, is the Law; but she that brought water, and did sprinkle it, is the Gospel. Now, whereas thou sawest, that so soon as the first began to sweep, the dust did so fly about that the room by him could not be cleansed, but that thou wast almost choked therewith; this is to shew thee, that the law, instead of cleansing the heart (by its working) from sin, doth revive, put strength into, and increase it in the soul, even as it doth discover and forbid it, for it doth not give power to subdue.

Again, as thou sawest the damsel sprinkle the room with water, upon which it was cleansed with pleasure; this is to show thee, that when the gospel comes in the sweet and precious influences thereof to the heart, then, I say, even as thou sawest the damsel lay the dust by sprinkling the floor with water, so is sin vanquished and subdued, and the soul made clean through the faith of it, and consequently fit for the King of glory to inhabit.

Allegory is simple only for those who don’t think about the symbols.

Every man and woman is a house. Every house has a parlor, the room where everyone sits comfortably in the easy chairs and sofas before the warmth of the fire. And every parlor has dust that must be washed away.3

Reading schedule for The Pilgrim’s Progress—note I’m describing the sections since there are no chapters:

April 29: Intro to the work and discussion of “The Author’s Apology for his Book”

May 6: Beginning to introduction of Simple, Sloth, and Presumption

May 13: Introduction of Simple, Sloth, and Presumption to introduction of Talkative

May 20: Introduction of Talkative to the By-Path Meadow

May 27: By-Path Meadow to introduction of the Atheist

June 3: From the Atheist to the end

You can read the work online here. Someone has already asked if we will read Christiana’s journey (part 2). I hadn’t planned to but I’m totally game! Let me know as we go along if you’d like that (or if you’ve had enough of the seventeenth century, haha!). We’ll take it as it goes.

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.” – Simone Weil4

I can’t let this passage go without mentioning my favorite song from my favorite musical (both stage and film versions). Here is Anne Hathaway in Les Miserables with “I Dreamed a Dream.”

https://apilgriminnarnia.com/2022/03/03/the-sloo-of-despond/

Here’s a very short video describing another allegory using a house. It’s wonderful. Thank you,

, for directing me to this!Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

The first time I read PP (a few decades ago now) I was terrified by the portrayal of the man in the iron cage in the Interpreter's house, in particular the statement "God hath denied me repentance". I think the edition I was reading referenced Heb. 12:17 for that point, which sounded (in the AV) like Esau was not permitted to repent because of his sin. It was many years before I came to see that verse in a different - and I hope more accurate - light: that Esau could find no repentance, no change of mind, in his father, Isaac. (Actually, the ASV adds 'in his father' to that clause which I think is warranted). That this wasn't about his final state, that he had committed a sin from which there was no way back (I wrote a piece on my 'stack a few years ago that suggests seeing Esau in a different light, through the lens of the parable of the Prodigal son - https://thewaitingcountry.substack.com/p/written-off?utm_source=publication-search).

Actually, that section in PP makes a lot of the warnings in Hebrews where I think I would also disagree with Bunyan's (and others') interpretation. Hebrews has several warning passages, all drawn from OT examples, which seem to me to be written for the church community in its present communal life, not warnings regarding the eternal fate of individuals within the community. When in theological college training for ministry I was really helped by a paper on Hebrews 6 in a theological journal that suggested the background for that passage was Isaiah 5 and emphasised the communal and temporal aspect - I then traced that through the letter and found the idea essentially holds for all the warnings. Well, to my mind at least!

(Karen, my apologies for the length of this comment!)

I had never thought before that there was ‘a plain style ‘ but I’d course there is. Would Willa Cather have been influenced by the plain style of the puritan writings of the seventeenth century?