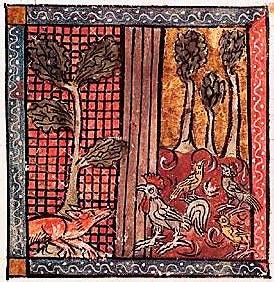

[A medieval illumination of Renart et Noiret from Dictionnaire Larousse]

[First, some breaking news I hope you don’t mind my sharing with you. Yesterday, Christianity Today announced the winners of their 2024 book awards, and The Evangelical Imagination, by yours truly, was named a finalist! Such would always be an honor, but there were so many excellent titles among the contenders that it was an even greater honor. I even endorsed some of these winners and other contenders! I hope you will check out the list here. And, of course, if you’ve not read The Evangelical Imagination, I hope you will consider doing so. It’s a tangible and helpful way to support my work. And if you have read it, please read an honest review anywhere that might serve other readers. Thank you!]

“Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.” – Simone Weil

Now, with The Nun’s Priest’s Tale, I get to go all English professor on you, dear readers. I am, believe it or not, a pedant at heart. (This is not a compliment, haha! Look it up here.) I love literary terms, definitions, and genres. (Remember, one of my specializations in my PhD work was eighteenth century British literature—can’t wait until we get there! And the Augustans loved their genres, their rigid categories, and definitional boxes. They were, after all, the quintessential Moderns.) So with this tale, I will focus a good deal more on the forms it employs and a bit less on the content of the story itself (which is easy enough to follow … and utterly delightful).

But let’s discuss the story a little bit. We see in it a number of recurring themes from The Canterbury Tales. Nobility (or gentilesse) is mentioned in passing. We see the way in which various authorities (authors) are invoked in a pastiche of surface-level knowledge as the world of oral tradition merges into a print culture, and ideas are handed down by tradition but not rigorously read. (Kind of like today’s digital age!) We see the tension between the Romantic worldview and deeply embedded misogyny and patriarchy. The counsel of the “woman” in the story (the hen, Pertelote) turns out to be bad advice (naturally), for indeed Chauntecleer’s dream foretells what is to come. Yet, ironically, Chauntecleer ignores his own (lengthy) words, and his sheer pride in his own voice nearly does him in in the end. Chaucer is always an equal-opportunity critic of male and female alike.

Now back to that pedantry. The Nun’s Priest’s Tale is a gallery of literary forms.

First, it is a fable. A fable is a brief tale told to point to a moral. Fables were tremendously popular in the Middle Ages, in part because of French influence (in particular a set around Reynard the Fox, who is echoed in this tale). Some fables, like this one, do more than point to the moral; they spell it out for you. And in this fable, we get not just one, but two morals! We find them in lines 611-15. The first is spoken by the rooster Chauntecleer (whose name means “clear song”), who has learned the hard way: May God not prosper the one who closes his eyes when he should see. The second moral follows immediately, spoken by Russel, the fox: May God give bad luck to the one so lacking in self-control that he chatters when he should hold his peace. The tale, needless to say, beautifully bears these lessons out.

Not only is this tale a fable more generally, but it also falls into the more specific subcategory of the beast-fable. A beast-fable is, just as it sounds, a fable that features beasts as characters, talking animals. This tale, we are told in lines 60-61, takes place back in the times when “beasts and birds could speak and sing.” (C. S. Lewis, as a scholar of medieval literature, came by his love of talking animals honestly.) Of course, the most famous within this genre of literature are Aesop’s fables, a collection of tales said to have originated with a Greek slave named Aesop (620–564 BCE) whose stories were handed down through oral tradition for centuries, picking up ever-new additions and variations along the way.

The Nun’s Priest’s Tale is also satire: a work that holds up human vice or folly for the purpose of correction. The list of human efforts and proclivities satirized is rather long for such a short tale. Among the objects of satire are Romantic literature, courtly love and courtly traditions (Chauntecleer is quite the courtly lover!), rhetorical excesses, medieval scholasticism, human pretension generally, and, more particularly, the human tendency to clothe our triumphs and misfortunes in high poetry, philosophy, and drama (“Not that there’s anything wrong with that!” as Seinfeld’s Jerry and George would say).

Now, it might not be immediately obvious that these things—treated with such depth, breadth, and seriousness in the tale—are being gently satirized. But we know this is the case if we understand another literary genre the tale falls into: the mock-heroic. The mock-heroic (and its close cousin the mock-epic) parodies Romantic, heroic events by treating trivial events in grand style. The barnyard discourse between Chauntecleer and his main squeeze Pertelote is given in a very grand style. They discourse over the meaning and significance of dreams, Roman philosophers, biblical prophecies, the tension between human free will and God’s foreknowledge (and mangle some Latin and discuss the causes and cures of lower digestive tract issues along the way). But what makes this a mock-heroic is the fact—so easy to forget once we are immersed in the story—is that these events concern chickens in a poor widow’s austere barnyard.

This framing of the story—the opening description of how bare, plain, and impoverished the widow’s home is—sets up the further contrast with the vain pretensions of the fowl in the yard. Chauntecleer’s coat might be glossy and red, his hue burnished like gold, his nails whiter than lilies, and his comb redder than fine coral—but he is a lowly creature inhabiting a lowly world. How easily he loses sight of his place in the larger universe of creation.

The chickens are us, dear reader.

We, the human beings, are the ones who get so caught up in our high faluitn’ book learnin’ and philosophizin’ and readin’ and writin’ and ‘rithmetic, our dreams and aspirations, our glossy feathers (and our harem of fine hens, one of whom our dear Chauntecleer “feathered” twenty times before 9 a.m. [lines 357-58]) and fine singing voices that we too easily talk too much and see too little.

Of course, being made in the image of our divine creator, our human efforts and accomplishments do matter. At their best, they reflect the nature and character of God. But apart from that they are—as the writer of Ecclesiastes shows and as Chauntecleer learns—mere vanity.

May we heed the lessons learned by Chauntecleer and Russel and speak less and see more.

*****

Next up:

(Note the additional tale from The Canterbury Tales at a reader’s request. It’s the longest of the tales, so give yourself time.):

The Second Shepherd’s Play ←— I’ve linked an online pdf. But I also recommend this cheap Dover edition if you, like me, prefer a book.) It’s a Christmas story! Make merry!

Christmas break! Enjoy family and friends!

And then we may as well just go ahead and celebrate the New Year with a play about death: Everyman (It’s in the Dover edition linked above and also here.)

Then we shall turn to the Bard himself … Shakespeare. Jack Heller, one of the members of this little community, will write a guest post on Romeo and Juliet. And we will cover some of the sonnets. Is it spring yet?

So! That's where Walter Wangerin got the characters in his Dun Cow trilogy!! Pertelote, Chauntecleer, Russel the Fox - they're all from Chaucer and from this tale in particular. I never knew (or if I knew I'd completely forgotten). As fantasy novels I'm not sure you'll know them, Karen (that's not a criticism, just recalling you said somewhere that it's not a favourite genre of yours), but they're hugely enjoyable and telling in so many ways. Now I need to think about how much of this tale Wangerin actually appropriated, if not just the characters and their names. I guess that's the kind of thing all authors do - taking and refining, taking and reframing.

Oh, also want to say: I hope you do well in the CT awards, the book deserves to do so. I'd put it in my top 10 of books read this year for sure. Bravo!

Ahhh! Thank you for this lovely breakdown of the tale I cut my Senior-English-Teacher teeth on! This is too well-phrased! I can't even....

"The chickens are us, dear reader.

We, the human beings, are the ones who get so caught up in our high faluitn’ book learnin’ and philosophizin’ and readin’ and writin’ and ‘rithmetic, our dreams and aspirations, our glossy feathers (and our harem of fine hens, one of whom our dear Chauntecleer “feathered” twenty times before 9 a.m. [lines 357-58]) and fine singing voices that we too easily talk too much and see too little."

On my current hiatus from teaching high school English, as a new mom, I now see how little I was seeing as I tried to guide students through literature!