(Welcome new readers! If you have joined us here at The Priory for this next read, The Pilgrim’s Progress, you are in the right place! The reading schedule is below. (If you are here for occasional reflections on publishing and more personal musings, you are still in the right place!) I hope you enjoy the series enough to consider becoming a paid subscriber as a way of supporting this work—and so as to join in on the comments, which is where the real action happens!) Now on to the show …

For centuries, The Pilgrim’s Progress was second only to the Bible in availability and popularity. Since it was first published in 1678, it has never gone out of print. The world is filled with endless variations and adaptations of the work, including children’s versions, abridged editions, annotated editions, modernized versions, movie adaptations, stage plays, and animated films. One notable adaptation was one written and produced by Louisa MacDonald (wife of George) that centered on the second part of The Pilgrim’s Progress which concerns the journey of Christian’s wife, Christiana. (That one is for you,

!)In 2013, the British newspaper The Guardian chose this work to lead its series on the 100 Best Novels. Technically, The Pilgrim’s Progress is not a novel, but its role in giving rise to the novel is so significant that we’ll let it go. Just a few of the great novels that engage with it directly are Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte, Little Women by Louisa May Alcott, The Celestial Rail-Road by Nathaniel Hawthorne, Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray, The Pilgrim’s Regress by C. S. Lewis, and Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut. Composer Ralph Vaughn Williams composed a four-act opera based on the work in 1952.

If one knows anything about The Pilgrim’s Progress, likely that is its most characteristic and memorable literary quality: it is an allegory. An allegory is a story in which all or most of the characters and events are symbols. Each symbol (or similitude, as he calls it in the full title of the work included below) has two levels of meaning—the literal, surface level and the deeper level that conveys the real spiritual or philosophical meaning of the story. Allegory really only works when the symbols and the story they tell work on both levels, the literal and the symbolic. The central allegory of “life as journey” was, of course, already common. (In fact, as we saw earlier in our studies, it’s the basis of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.) Bunyan takes an already-familiar symbol and fills it out into a feast.

Creating an effective allegory is not as easy as Bunyan makes it look. That’s something to keep in mind as we read: Bunyan makes the symbolic meaning so clear that it almost seems like child’s play. Yet, the theological, spiritual, and psychological insights he brings to bear on the story require an uncommon level of genius.

In a lecture C. S. Lewis delivered over BBC radio, Lewis offers good guidance into how to read allegory. We ought not, Lewis warns, read allegory,

… as if it were a cryptogram to be translated; as if, having grasped what an image (as we say) ‘means,’ we threw the image away and thought of the ingredient in real life which it represents. But that method leads you continually out of the book back into the conception you started from and would have had without reading it. The right process is the exact reverse. We ought not to be thinking “This green valley, where the shepherd boy is singing, represents humility”; we ought to be discovering, as we read, that humility is like that green valley. That way, moving always into the book, not out of it, from the concept to the image, enriches the concept. And that is what allegory is for.

We’ve looked at allegory elsewhere in our survey of British literature at The Priory, but The Pilgrim’s Progress is, hands down, the most famous and exemplary allegory in all of literature. (Well, maybe after Plato’s Allegory of the Cave.)

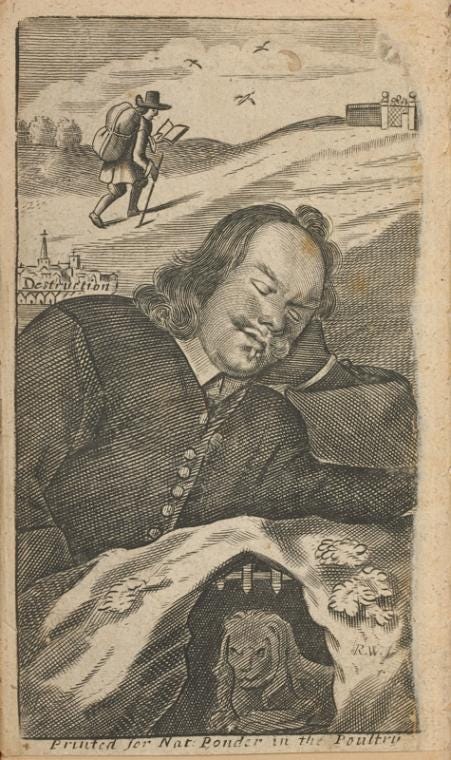

The Pilgrim’s Progress is meant to be the allegory of every Christian’s life. And it certainly reflects the life of its author. John Bunyan, who lived from 1628 to 1688, served in the parliamentary army during the English Civil War, on the side of the Puritans who were fighting against the Royalists serving on the side of the crown. While the journey to his conversion to genuine Christian faith was long and bumpy, by 1655 he had undergone a genuine conversion to Christianity and was preaching to dissenting congregations. Those dissenting from the Church of England (called Dissenters) found themselves in varying states of legality during these years, and Bunyan ended up imprisoned twice when his preaching put him on the other side of the law. He suffered one of the longest jail terms ever served by a Dissenter in England.[1] In prison—where he had with him a copy of the Bible and Foxe’s Book of Martyrs—Bunyan wrote his spiritual autobiography, Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners (published in 1666), and began the work that would become The Pilgrim’s Progress (published in 1678). Both works display a mind steeped in the Bible and enlivened by a rich imagination.

Bunyan’s use of allegory derives from both a negative and a positive view of how language functions. The negative is rooted in the Puritans’ suspicion of fiction and fables since these stories are not “true.” This is the reason for Bunyan’s need to defend even writing such a “fabulous” work in the first place, as we will see in looking at the poem that serves as the preface to The Pilgrim’s Progress.

But allegory is also rooted in a positive view of the Puritans. As I explain in my chapter on The Pilgrim’s Progress and the virtue of diligence in On Reading Well: Finding the Good Life in Great Books:

For the Puritans, the world constituted a “book of nature,” one filled with emblems pointing to spiritual truth that might be discovered through interpretation based on the logic that underlies an understanding of how similitudes (such as symbols and analogies) work. Despite being iconoclasts who eschewed graven images, the Puritans inherited from the medieval worldview “mental habits of conceiving abstractions pictorially.” Interpretations arising from observations of the “book of nature” were seen not as creating fictions but rather simply uncovering meanings already inhering in the world by God’s design. Such a “metaphorical mode of thinking” was prone to producing and appreciating allegory.[2] Allegory depends upon a thick understanding of the physical world and the language that bridges that world with the spiritual one. Whereas the modern fiction writer creates out of her imagination, the pre-modern allegorist simply translated from the book of nature.

Modern ways of thinking sometimes cultivate a flatter approach to language and stories—as well as to the world and truth—than our ancestors had. This modern preference for the literal over the symbolic, metaphorical, and poetic lends itself to a fundamentalism that the Puritans would never have recognized. For the Puritans the world, and language itself, was charged with meaning both originating in and pointing toward God. For example, it is impossible to understand the meaning of marriage apart from an understanding of how marriage is an emblem for the relationship of Christ and the church. To separate the poetic nature of marriage (as allegorical and anagogical) is to change its meaning altogether. When the ties between layers of meaning inherent in language are broken, then our own ability to know and grow in truth is hindered.

Even the word progress in the title The Pilgrim’s Progress is suggestive of how allegory functions. Allegory operates on a built-in expectation of readers to “progress” from the literal, material level of the story to the symbolic, spiritual truth beyond. It has an explicit assumption of interpretation that is implicit in all literary writing, indeed in all writing and all use of language. In other words, allegory requires and assumes the exercise of diligence by readers.

I’ve gone on so long already and promised we would cover “The Author’s Apology for His Book.” (I guess I must apologize as well!) Let me go on a bit more by pointing out a few fetching lines from the Apology. (My edition does not include line numbers, so I will not here either.)

I love the way Bunyan describes his writing process:

When at the first I took my pen in hand

Thus for to write, I did not understand

That I at all should make a little book

In such a mode; nay, I had undertook

To make another; which, when almost done,

Before I was aware, I this begun.

And in this way, he continues, he “fell suddenly into an Allegory.” Ah, yes, so much of writing is indeed a “falling into.”

Like any good writer, Bunyan even circulates the manuscript among his friends to get feedback. Some loved it, and some told him to trash it! “Since you are thus divided,” Bunyan responds, “print it I will!” (LOL!)

But the bulk of this apology is exactly that: an apology—or defense—of his writing a fictional work (in his word, “feigned”) by using “metaphors.” In defending metaphors, he uses more metaphors. He likens such “similitudes” to “dark clouds” that “bring waters” that yield crops. He compares writing in metaphors to the work of the fowler catching game “by divers means.” It is like a pearl hidden in an oyster shell. He points out that the Bible uses “types, shadows, and metaphors,” too. Ultimately, he argues, that this method is no “abuse” of language, but rather an “advance of Truth.”

It seems a novelty, and yet contains

Nothing but sound and honest gospel strains.

Schedule for The Pilgrim’s Progress (Lord willing!)—note I’m describing the sections since there are no chapters:

April 29: Intro to the work and discussion of “The Author’s Apology for his Book”

May 6: Beginning to introduction of Simple, Sloth, and Presumption

May 15: Introduction of Simple, Sloth, and Presumption to introduction of Talkative

May 22: Introduction of Talkative to the By-Path Meadow

May 29: By-Path Meadow to introduction of the Atheist

June 6: From the Atheist to the end

You can read the work online here. Someone has already asked if we will read Christiana’s journey (part 2). I hadn’t planned to but I’m totally game! Let me know as we go along if you’d like that (or if you’ve had enough of the seventeenth century, haha!). We’ll take it as it goes.

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.” – Simone Weil

[1] W. R. Owens, Introduction to The Pilgrim’s Progress, xvii.

[2] J. Paul Hunter, “Metaphor, Type, Emblem, and the Pilgrim ‘Allegory’,” in The Pilgrim’s Progress, ed. Cynthia Wall, W. W. Norton, 2009, 408-409.

There is something deeply consoling in your reflection — a reminder that the old pilgrim paths are not abandoned, only overgrown by modern forgetfulness. At Desert and Fire, I often return to this same truth: that the world, rightly seen, is not mute but filled with living signs, charged with the radiance of a God who stooped low enough to write His Word not only on parchment but into flesh, landscape, and sorrow.

Incarnational mysticism insists that allegory is not a flight from reality, but a deeper plunge into it. Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress is not a "fiction" in the modern sense — it is an uncovering of what already burns beneath the skin of the world. The green valleys, the dark sloughs, the glittering cities — all are not mere metaphors of the soul’s journey, but incarnations of it, visible to the eyes that have been washed by suffering into clarity.

Modern literalism, as you so well point out, flattens this vision; it forgets that to walk through the world is already to move through a woven tapestry of spirit and matter. To lose this is not merely to lose poetry — it is to lose the very texture of God’s self-disclosure.

Thank you for reminding us that to read Bunyan rightly is not to decode, but to consent — to allow his images to reawaken the forgotten hunger within us for the long road home, a road where the dust on our feet is itself sacramental, and every burden borne for the King becomes, secretly, a hidden crown.

The line in Bunyan's Apology:

"nor did I intend But to divert myself in doing this From worser thoughts which make me do amiss" would seem like a reference to the unwanted thoughts that he said would come suddenly into his mind in his autobiography, Grace Abounding. As you know, it is mine and others' theory that Bunyan suffered from religious scrupulousity, a common symptom of what is now known as OCD.

I would love to go on to part two, which has its own cast of interesting characters. In my youth, I always preferred part two to part one, as it seemed more hope filled. Bunyan is gentler on the women and children in the second part than he is on poor Christian in the first.

Vaughan Williams' Fifth Symphony was also originally based on Pilgrim's Progress. Vaughan Williams took the manuscript references Pilgrim's Progress out before the symphony's publication, as he was trying to move away from program music [program music, based on a narrative or topic, is often considered less 'serious' than absolute music, which has no topic or narrative, and Vaughan Williams wanted to be taken seriously]. The 5th symphony is my favourite by Vaughan Williams and I hear Bunyan's story in it, especially in the beautiful 3rd movement, the Romanza: https://youtu.be/oX4pTSRcgSc?feature=shared