“A man is a bubble.”

These are the opening words of The Rules and Exercises of Holy Dying, published in 1651, by Jeremy Taylor (1613-1667), a contemporary of John Bunyan. Like Bunyan, Taylor was a clergyman. He was, however, in a religious and political tradition opposing Bunyan. While Bunyan was a nonconformist Puritan, Taylor served in the Church of England. Like Bunyan, Taylor spent time in prison owing to his clerical calling. Because he served as chaplain to King Charles I, Taylor became a political enemy under Cromwell and was imprisoned several times along with other Royalists during the English Civil War. It’s not likely that Bunyan and Taylor knew one another or each other’s works, but they swam in the same cultural waters, despite their doctrinal, educational, and social differences. Sharing in some of the same social imaginaries, they would have shared common metaphors, such as the metaphor that man (or in Bunyan’s case, “Madam”) is a bubble.

Why do I begin this last installment in our long, slow read of The Pilgrim’s Progress Part 2 with Jeremy Taylor? Because I want to return to what makes The Pilgrim’s Progress what it is—a work of a metaphorical imagination.

Such an imagination is displayed by both the Anglican Jeremy Taylor and the Puritan John Bunyan—both men of their times. And their times were rich in the understanding of language, metaphor, and their power, as were many who came before them and after—although, perhaps not for long after, as I believe that one of the ailments of our time is a too-literal imagination, one flattened and hollowed out by an impoverished sense of words. A metaphorical imagination as I am defining it here is one that understands and revels in the layered resonances of language and words, their accumulated histories, connotations, implications, nuances, connections, allusions, and relations. In short, the poetry of language and the way it translates into a poetic view of life.

I was inspired to bring Taylor, specifically, into this conversation because of Bunyan’s character Madam Bubble, whom we encounter in the reading for today. Of the many minor characters we meet in this pilgrimage, she is among the most colorful. She is a witch, of the kind we encountered in The Wife of Bath’s Tale: both young and old. I am reminded, too, of the witch in The Wizard of Oz who offers pilgrims sleep in her field of poppies on their journey to the Emerald City. Here, in The Pilgrim’s Progress, Madam Bubble offers sleep (among other things) in the Enchanted Ground. She is a symbol of the life of vanity:

This is she that maintains in their splendour all those that are the enemies of pilgrims. Yea, this is she that has bought off many a man from a pilgrim's life. She is a great gossiper; she is always, both she and her daughters, at one pilgrim's heels or other--now commending, and then preferring the excellences of this life. She is a bold and impudent slut; she will talk with any man. She always laughs poor pilgrims to scorn; but highly commends the rich. If there be one cunning to get money in a place, she will speak well of him from house to house. She loves banqueting and feasting mainly well; she is always at one full table or another. She has given it out in some places that she is a goddess; and therefore some do worship her. She has her times and open places of cheating; and she will say and avow it, that none can show a good comparable to hers. She promises to dwell with children's children, if they will but love and make much of her. She will cast out of her purse gold like dust, in some places and to some persons. She loves to be sought after; spoken well of; and to lie in the bosoms of men. She is never weary of commending her commodities; and she loves them most that think best of her. She will promise to some, crowns and kingdoms, if they will but take her advice; yet many has she brought to the halter, and ten thousand times more to hell.

Madam Bubble embodies all that is vanity of vanities.1

The metaphor of life as a bubble was common during Bunyan’s lifetime, as the line I quoted above from Taylor indicates. In fact, Taylor states specifically that he is quoting Lucian, a second-century Greek satirist. The same saying is also found among the adages of Erasmus.2 Like Madam Bubble, this metaphor got around! In fact, the phrase “man is a bubble” was so common that it became a Latin proverb: homo bulla est (or merely homo bulla).

Jeremy Taylor expands on the metaphor after his opening line in The Rules and Exercises of Holy Dying:

… all the world is a storm, and men rise up in their several generations, like bubbles descending … from God and the dew of heaven, from a tear and drop of rain, from nature and Providence; and some of these instantly sink into the deluge of their first parent, and are hidden in a sheet of water, having had no other business in the world, but to be born, that they might be able to die: others float up and down two or three turns, and suddenly disappear, and give their place to others: and they that live longest upon the face of the waters are in perpetual motion, restless and uneasy; and, being crushed with a great drop of a cloud, sink into flatness and a froth; the change not being great, it being hardly possible it should be more a nothing than it was before. So is every man: he is born in vanity and sin; he comes into the world like morning mushrooms, soon thrusting up their heads into the air, and conversing with their kindred of the same production, and as soon they turn into dust and forgetfulness …

This metaphor of human life as a mere bubble—fragile, transitory, and almost nothing—is so evocative and full of truth.

If you’ve been reading along here at The Priory for any length of time, you know that death has been a recurring theme, both in the literary texts we’ve read and in my own life. From Everyman to Dr. Faustus to Christian and Christiana, to my own mother (who lived a good, long time) to my friend Jennifer Lyell (who died far too soon), we have been reminded over and over how short our lives are in the end.

This is why Jeremy Taylor wrote The Rules and Exercises of Holy Dying and did so several years after writing its companion piece, The Rules and Exercises of Holy Living. Because the truth is we only know how to live well in light of understanding how to die well. And this, ultimately, is what Bunyan is trying to teach us in The Pilgrim’s Progress.

Our physical lives may be short, but their influence can be long. Mr. Valiant perseveres in his journey because he had heard about Christian’s journey from the City of Destruction to the Celestial City and Valiant was inspired to follow in Christian’s footsteps. The meaning of Christian’s life far outlives his actual life. Christian lives a life that ends but lives on in the story his life tells.

So indeed all of our lives are literal—and metaphorical.

What metaphors will our lives tell after we are gone?

Will they be metaphors for Mr. Brisk, Heedless, or Too-Bold? For Grim the Giant, the Giant Despair or Mr. Selfwill? Or will our lives be metaphors for Old Honest, Charity, Prudence, Mercie, Mr. Valiant, Mr. Steadfast, Christiana, and Christian?

A human being is a bubble.

Jesus is the living water. Bubbles rise up and burst in an instant. But rivers of living water flow eternally from those who believe in him.

***

What’s next:

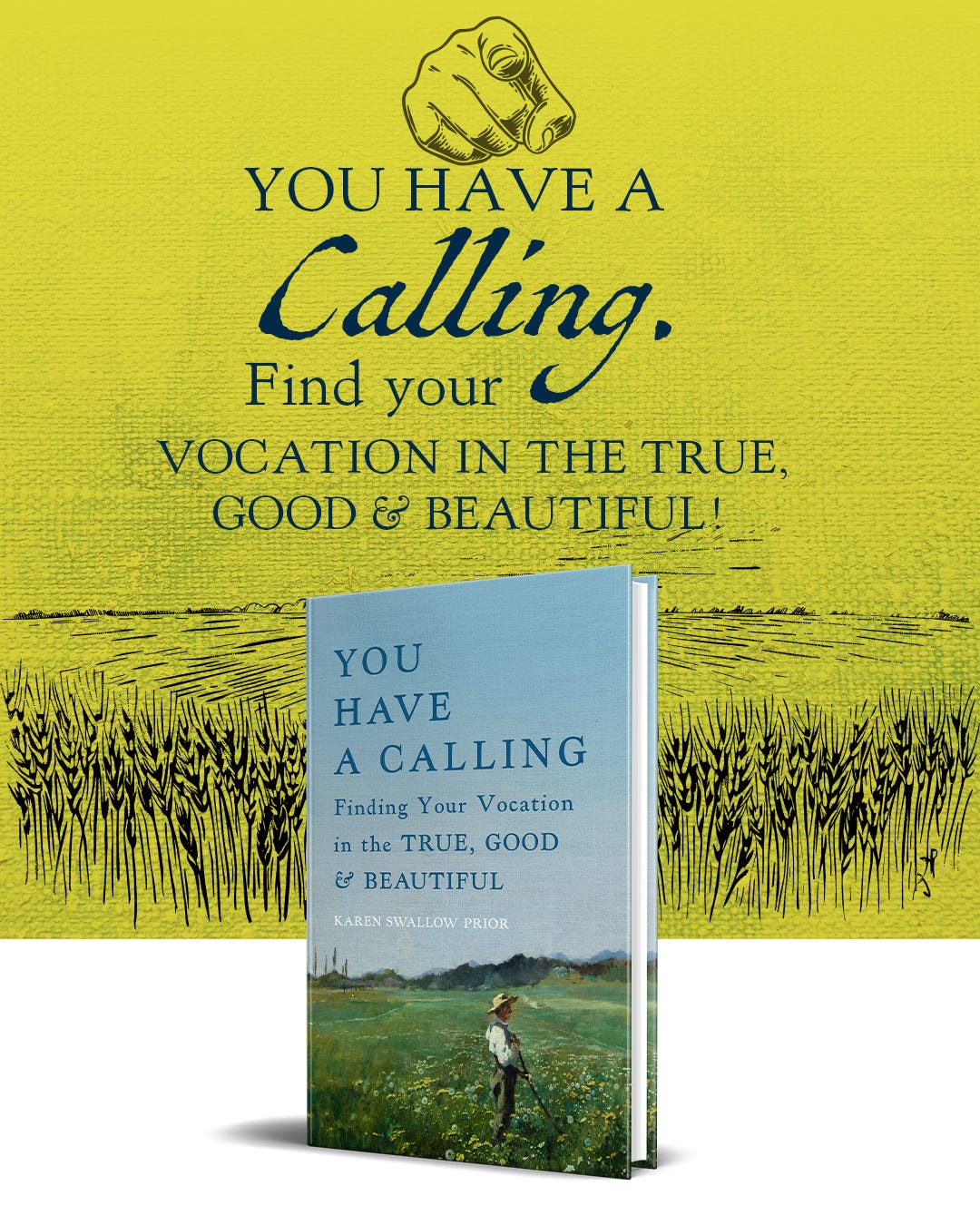

What’s really up next is the release of my new book, You Have a Calling (in case you haven’t heard!). See below for how to pre-order and attend my Zoom meeting with all who do so!

We will take a break from “class” for a bit while I run some interviews with folks on their own callings. This is going to be good! These conversations will be rich and enlightening—and I hope will encourage you in thinking about your own callings in life.

Come late August or September we will pick up our reading with the English Neoclassical poet Alexander Pope! We will start with An Essay on Man and see what your pleasure is from there, readers. I’m curious if you are familiar with Pope already, and if so if you enjoy him or not. If you don’t know him, I can’t wait to see what you think! Oscar Wilde was not a fan. He famously quipped, “There are two ways of disliking poetry; one way is to dislike it, the other is to read Pope.”

***

One additional request before sharing the details about my book: I hope you can see how much work I put into these posts and how many years of study I’m drawing on even to write these short essays. It is a labor of love, and it means so much to have every reader and subscriber I have here. So, thank you. Thank you for not letting me labor in vain. If you have not become a paid subscriber and are able to do so, I would be so grateful. Other ways to support my work are to simply share these posts with others (that’s free!) and to read, buy, or review my books, too. (Amazon reviews really, really help!). Thank you for considering any and all of these ways to keep me going as my calling shifts.

More about my new book:

PRE-ORDER You Have a Calling between now and Aug. 4 and gain immediate electronic access to the book through NetGalley by clicking the image above or here . (You will still receive the beautiful hardbound copy at release time. And may I repeat? It is beautiful!)

Pre-order between now and August 4 and you can register for a free Zoom call with me discussing the book to be held on August 4 at 8 p.m. ET.

Consider You Have a Calling for your small group or classroom!

Discounts are available for bulk orders of 10 or more copies. See details here. Or contact Adam Lorenz of Brazos directly if you need special arrangements for your school or organization. He will set you up: alorenz@bakerpublishinggroup.com

A free, downloadable discussion guide will be available when the book is officially released Aug. 5

You Have a Calling is a perfect book for high school seniors, college students, early-career folks, and mid- or late-career veterans — all stages of life — because we all have various callings at various stages of life. You, yes, you, have a calling!

(It’s also perfect for reading, contemplating, and marking up on your own, too—just a note for all my introverts out there.)

I am really excited about this book. I wrote it during a time of professional, personal, and spiritual transition. I hope and pray it serves you in reading it as much as it did me in writing it.

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.” – Simone Weil3

I will note that Madam Bubble is also describe as “swarthy,” a continuation of the negative portrayal of dark-skinned people during this time (and our own). Grateful for the longer post written on this topic by

earlier in this series, here.The Adages of Erasmus (selected by William Barker, (University of Toronto Press, 2001), pp. 171-172.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

As a musician, with extensive experience in church music, I hear all the music in this last section.

First, there is Valiant's hymn, 'Who would true valour see', since modernized to 'He who would valiant be', a favourite of the English public school. My favourite recording of it, by Maddy Prior (former lead singer in the English folk rock group Steeleye Span) and the Carnival Band, has the original words, performed in the old 18-19th church quire style. The quire, immortalized in Thomas Hardy's 'Under the Greenwood Tree' and depicted in Elizabeth Goudge's 'The Little White Horse', was essentially a village band that would accompany the congregational singing from the back gallery (the balcony along the back of the church). This is a sample of what it sounded like: https://youtu.be/KY3MnQRVmOc?feature=shared

Then there is the beautiful passage when they reach Beulah:

"where the sun shineth night and day. Here because they were weary, they betook themselves awhile to rest... But a little while soon refreshed them here; for the bells did so ring, and the trumpets continually sounded so melodiously, that they could not sleep, and yet they recieved as much refreshing as if they had slept their sleep ever so soundly."

When I was in Athens, the bells of the neighbouring churches early every morning never ceased to make me smile, however little I had slept (and I was having trouble sleeping). The Orthodox bell-ringing is in a very different style than the bell-ringing my father and others used to do on Sunday mornings, but there is a joyful familiarity to both.

I mentioned in my essay last week that Bunyan, early on in his spiritual journey, had given up bell-ringing, a thing he loved to do, out of fear of being worldly. So this passage is highly significant to his own maturity and is also somewhat defiant of his own Puritanical bent, as the Puritan Protectorate under Cromwell, which Bunyan lived under, banned all bell-ringing, except for religious services.

I also mentioned last week that Christiana reminded me of my maternal grandmother. The end of Christiana's journey, where her companions gather to see her off, does too. My grandmother died of cancer while local hospitals were under lockdown due to the SARS outbreak in 2002-3. After being screened for symptoms and contacts, and required to wear masks while not in the private room, we were allowed in to see her and say goodbye. They also allowed me to bring my violin. The last hymn I played for her was the Crimond/Irvine setting of Psalm 23, 'The Lord's my Shepherd, I'll not want'. I played it again at her funeral.

First of all, thank you for leading us through PP 1&2. I have learned so much, and never have I appreciated Christiana’s story more.

Secondly, thanks for connecting Taylor and Bunyan. I have long loved Taylor’s Rules of Dying - so deep. If anyone reads it, I highly encourage the unabridged version. Taylor and Bunyan swam in the same waters, but on opposite sides of the pool - so they both used the bubble metaphor. I confess to not understanding it before, so thanks for those insights!