[Image credit: https://streetsdept.com/2016/02/11/inside-an-abandoned-northeast-philadelphia-warehouse/]

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.” – Simone Weil1

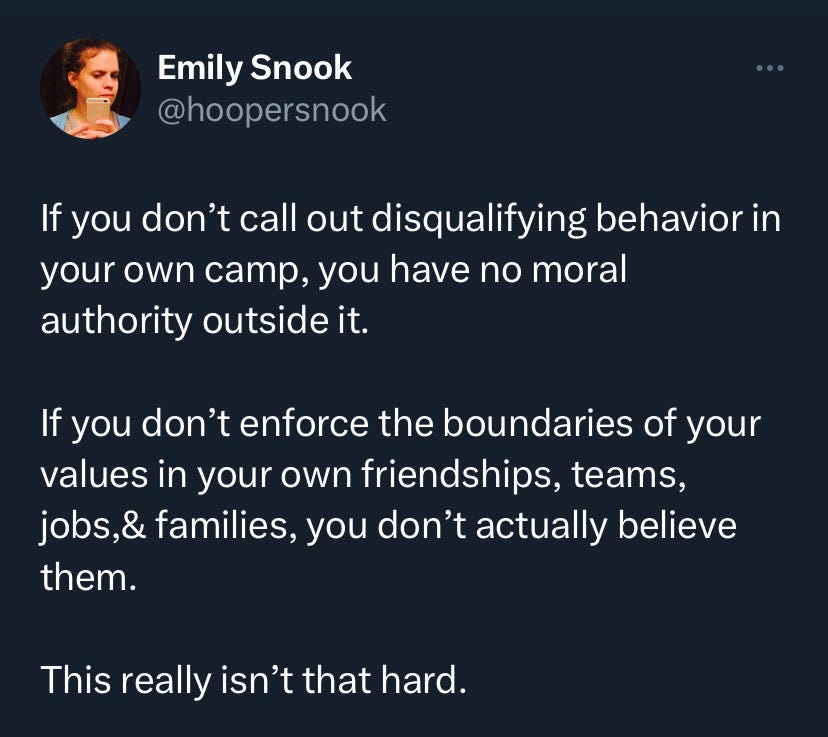

A few weeks ago, a friend of mine on X posted this:

When this truth bomb landed, a lightbulb went on.

There was something about that part about having moral authority outside the camp that illuminated something for me.

So many people call out from within their own camps the disagreeable behavior of those outside their camps. These folks call out loudly, publicly, indignantly, righteously, piously, clangingly (if I may coin a word). It’s almost as though they aren’t even trying to convince, convict, or persuade the people in the other camp.

And that was the lightbulb moment.

It’s not about actually convincing or persuading those outside the camp. It’s about building and maintaining moral (or even immoral) authority within their own camps.

Now, as soon as I write this out, I realize it is such a painfully obvious truth, one countless others have realized before me, that I’m almost embarrassed to state it here as though I have only just discovered it.

But I don’t think I have just discovered it as much as the truth of it has finally sunk in.

Denouncing those outside the camp confers moral authority within the camp. And it’s within the camp where all the personal, political, and economic benefits are to be gained. For many, moral authority outside the camp isn’t even the point. But claiming you want a certain change in society or the culture in the world outside the camp sure can confer a lot of power and privilege inside the camp.

Now, there’s nothing inherently wrong with “preaching to choir.” (The choir needs a good word, too.) But start paying attention to who is only preaching to the choir, only speaking from podiums faced by like-minded people, only writing for already-convinced readers, and so on. These efforts don’t gain any authority (moral or otherwise) outside the camp.

Then watch what happens to people who do seek conversation outside the camp.

Really.

Watch.

There’s a passage in Eugene Peterson’s Eat This Book that stopped me cold when I read it not long ago. It’s an illustration, Peterson notes, that he bases on a famous one given by Karl Barth. As I began to read this little parable by Peterson, I thought I was just getting a nice little updated version of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. Then I got to the last two sentences (which I’ve emphasized in the quote below), and that same lightbulb (more like a spotlight) came on again:

Imagine a group of men and women in a huge warehouse. They were born in this warehouse, grew up in it, and have everything there for their needs and comfort. There are no exits to the building but there are windows. But the windows are thick with dust, are never cleaned, and so no one bothers to look out. Why would they? The warehouse is everything they know, has everything they need. But then one day one of the children drags a stepstool under one of the windows, scrapes off the grime, and looks out. He sees people walking on the streets; he calls to his friends to come and look. They crowd around the window ---they never knew a world existed outside their warehouse. And then they notice a person out in the street looking up and pointing; soon several people are gathered, looking up and talking excitedly. The children look up but there is nothing to see but the roof of their warehouse. They finally get tired of watching these people out on the street acting crazily, pointing up at nothing and getting excited about it. What’s the point of stopping for no reason at all, pointing at nothing at all, and talking up a storm about the nothing?

But what those people in the street were looking at was an airplane (or geese in flight, or a gigantic pile of cumulus clouds). The people in the street look up and see the heavens and everything in the heavens. The warehouse people have no heavens above them, just a roof.

What would happen, though if one day one of those kids cut a door out of the warehouse, coaxed his friends out, and discovered the immense sky above them and the grand horizons beyond them? That is what happens, writes Barth, when we open the Bible ---we enter the totally unfamiliar world of God, a world of creation and salvation stretching endlessly above and beyond us. Life in the warehouse never prepared us for anything like this.

Typically, adults in the warehouse scoff at the tales the children bring back. After all, they are completely in control of the warehouse world in ways they could never be outside. And they want to keep it that way.2

Let me repeat: “They are completely in control of the warehouse world in ways they could never be outside. And they want to keep it that way.”

Bingo.

To my shame, I have been bamboozled over and over by the warehouse keepers.3

I am trusting by nature, to be sure. But I also have been formed in ways that make me inclined to trust more easily those who are in power, those who claim authority, those who promise that they are using their power and authority for the work of the Lord.

Some of these warehouse keepers know exactly what they are doing. But I am more and more convinced that some of them lie to themselves first. They don’t care because they think that the things that are actually wrong are simply normal. So they maintain the warehouse—and the illusion that it is the real world.4

I have known warehouse managers who are ruthless and depraved (some proudly so). I have known ones who are kind. I have known those who are bullies. I have known ones who bully with kindness.

I know a bully who, if subjected to a lie detector test about his own bullying, would pass with flying colors. He’s as sweet as corn syrup, as folksy as grandma’s homemade cotton quilt, and as beloved as can be. I’m certain he has no idea that he’s a bully. Sometimes the first ones these guys gaslight are themselves.

The classroom bully knows he’s a bully because he’s a rebel against the system. But this other sort of bully has been formed and elevated within a closed system that knows little else. These bullies are like those blind fish who live in habitats so deep and dark that they lack functional eyes.

“Though seeing, they do not see; though hearing, they do not hear or understand” (Matthew 13:13 NIV).

Here at The Priory, I have committed myself to being intentional about paying more attention to the good, true, and beautiful—in other words, to seeing and hearing the beauty of the Lord (which, as I noted in my first post, does not mean ignoring ugly truths such as those I’m addressing here because justice demands that we attend to injustice).

In that spirit, the spirit of remembering that “attention is the beginning of devotion” (Mary Oliver5), I want to point you to a stunning and utterly convicting article by David Brooks in the current issue of Comment,6 “The Feminine Way to Wisdom.”

Brooks discusses several women who, in the context of the horrors they experienced at the hands of the Nazis—the ultimate warehouse keepers—transformed their lives simply by transforming the ways in which they paid attention.

One of these women is Simone Weil, the subject of my first two newsletters. Another is Etty Hillesum, who, although ultimately murdered at Auschwitz, “resolutely refused to hate the Nazis—refused to let Nazi barbarism evoke the same kind of barbarism in her own heart.” Edith Stein, also known as St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, a Jewish philosopher who converted to Catholicism before also being murdered at Auschwitz, came to understand that “the light by which we see the world is not something we produce; the light enters us through the glow of God’s love, and then we radiate that light onto the world.”

[In my TBR pile!]

I am turning to this article and its description of the lives of these remarkable women not only because these women are worthy of attention (they are so good, so true, so beautiful), but also because they are anti-bullies.

Perhaps the simplest way to define a bully is to say that he or she is attentive to self foremost and therefore is both blinded and blinding.

Bullies bamboozle.

These three women—anti-bullies—in contrast, Brooks writes,

… changed the way they saw the people around them, and were transformed. Or perhaps to put it more accurately, the Holy Spirit entered into each of their lives, and they saw the people around them by the light of that illumination.

Looking at the lives of these women, Brooks observes (with echoes of Simone Weil and Mary Oliver), “you begin to appreciate that attention is a moral act, maybe the primary moral act.”

May we, dear readers, see ourselves and others by such illumination.7

May we see the big, beautiful world outside the warehouse. And may we point the warehouse keepers—along with all others, whether inside or outside the camp—to the glorious sky above.

And if they cannot, or will not, see—we, by the grace of God, still can.

***

BACK TO CLASS NEXT WEEK: As I’ve said, there is no syllabus for this little course of mine. (But, there also are no tests or papers! Hooray!) Next week, we will start The Canterbury Tales! Again, I’m not sure how many posts I will make, but we will start with The General Prologue and see how it goes. Here is an online version that includes the text in both Middle and Modern English.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

Eugene Peterson. Eat This Book: A Conversation in the Art of Spiritual Reading. (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2006), 6-7.

This is not the first example, nor is it the last, of such bamboozling, but it serves well as an example. Some years ago, I endorsed a book. I believed in the book and its author. I still do. But somehow, before the book (or the endorsement) was published, I was contacted by an official of the SBC (Southern Baptist Convention, with whom I was then affiliated) and was asked to withdraw my endorsement. I asked why. I was told that a ministry partner had problems with the author. Because I am a “team player,” because I thought these leaders knew and understood more than I did, and because I trusted them, I agreed to withdraw my endorsement, as awkward as that was and as uncomfortable as that made me. Who was the ministry partner who had a problem with the book? It was Ravi Zacharias—who was later revealed to be a sexual offender who has been credibly accused of targeting and sexually victimizing numerous women.

I’m reminded of that masterpiece of a film, The Truman Show. If you’ve not seen it, you must.

Mary Oliver. Upstream. Penguin, 2016. p. 8.

For whom I’m honored to serve as a contributing editor.

I have not yet achieved the transformed and transforming attention exhibited by these women, and their feminine way of wisdom. But I am trying.

This piece causes me to reconsider every persuasive argument I've tried to make to get many in the tribe of American evangelical Christianity to confront unchristian behavior within their own ranks before calling out anyone outside.

I thought the pursuit of humility, self-correction, and winsomeness in the interest of having a good reputation with outsiders and winning souls for Christ was the whole point. Instead, it's about winning favor with the tribe by "owning" the outsiders. Their witness to the world is the least of their concerns.

Amen, and amen. Dear Jesus, give me strength through your grace to be the anti-bully, anti-narcissist, anti-gaslighter etc. Let me love others and lift them to the light. Understanding that I cannot control what direction they choose to look, let me still love and lift. Thank you for this word.