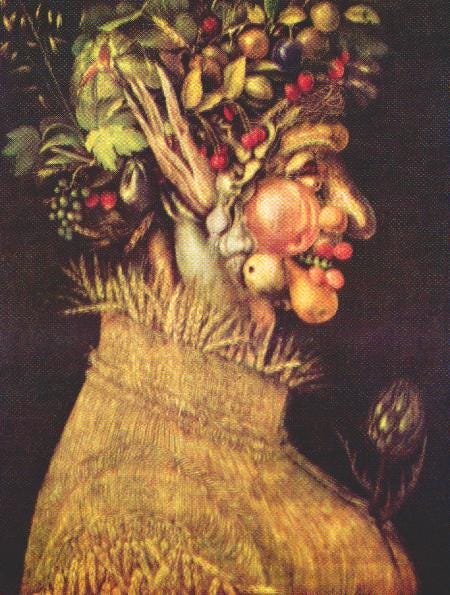

[Summer, by Guiseppe Arcimboldo, c. 1563. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna]

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.” – Simone Weil1

My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun;

Coral is far more red than her lips' red;

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks;

And in some perfumes is there more delight

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

That music hath a far more pleasing sound;

I grant I never saw a goddess go;

My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground.

And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare

As any she belied with false compare.

This sonnet is so fun, so witty, and so profound all at once. No wonder it is one of the most famous ones. I couldn’t not write about it! (Here is an outstanding reading of it for your listening joy.)

If you’ve studied this sonnet before, you know the joke, so to speak. But let’s pretend you don’t know, that you haven’t read this one before, and let’s approach it as though for the first time. Let’s also approach it knowing what a sonnet is and how the structure of a Shakespearean sonnet, specifically, helps us understand how the thought develops through the form: three quatrains followed by a couplet, each carrying some unit of meaning.

We expect immediately with the reference to the mistress in the first words that this will be a sonnet about love (and that expectation proves correct, although it is also about more). But then we read that that this lover’s eyes are “nothing like the sun” and that her lips are not red like coral (not even close!). What is going on here?? Then the speaker says that compared to the whiteness of snow the mistress’ breasts are a dull-colored brownish/gray?

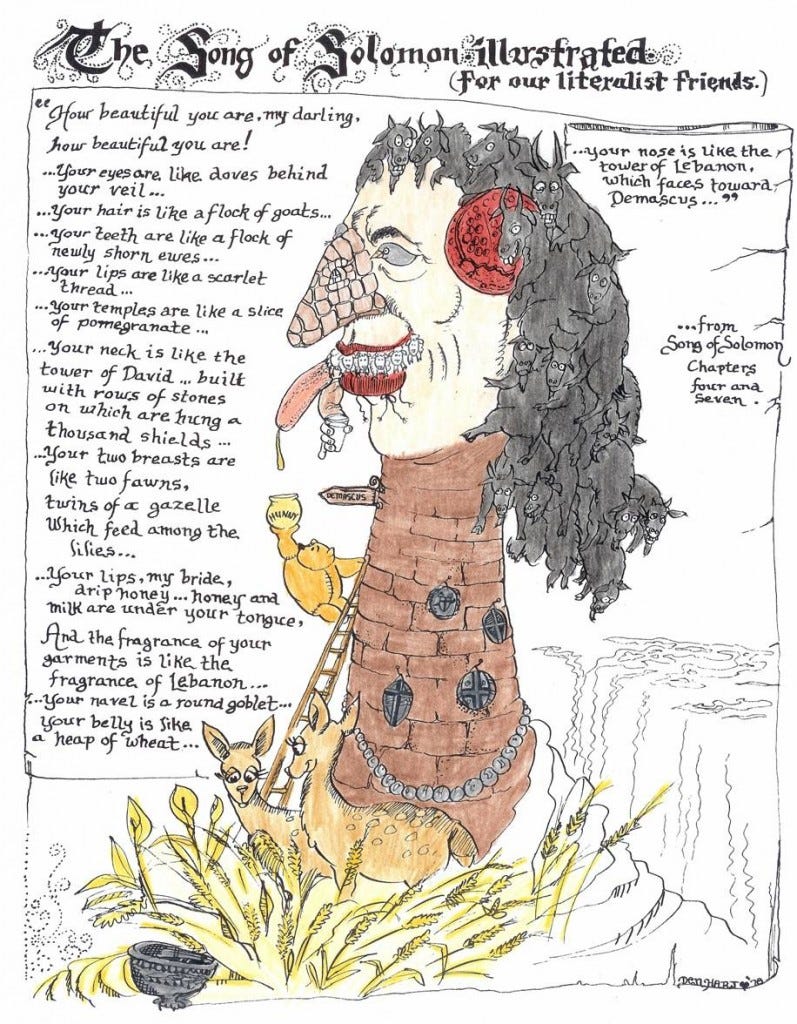

(Side note: every time I discuss this sonnet, I’m reminded of this literal rendering of the love imagery used in the Song of Songs:

Unlike Western poetry, Hebrew poetry, at least in this case, did not use similes that were intended to offer visual comparisons.)

Upon our first reading, these lines appear to insult the beloved and degrade her looks. It seems, at first, that here is a lover complaining about “the old ball and chain.” My gander is up at this point. And it only gets worse as it goes along: her hair is black like wires,2 she does not have rosy cheeks, and her breath does not smell like perfume. Her voice is not as pleasing as music and rather than flying or floating like a goddess, she walks on the ground.

Horrible, right?

But …. not so fast. Let’s look at what the poet is saying more closely. If we attend closely to the text, we learn this woman has:

Eyes not like the sun

Lips less red than coral

No actual roses in cheeks

Breath that does not smell like perfume

A normal voice

No wings

This woman sounds … normal.

Real.

Right?

Refreshing.

And we know that this is the point the sonnet is making because of that closing couplet. Until we get there, it really could go either way. Either these lines are mocking the lover whose beauty does not compare well to a summer’s day, etc. — or these lines are mocking such comparisons.

The conclusion of the poem makes clear that the subject of the sonnet is “false compare” — specifically, the false comparisons that comprise many images found in traditional love poetry. These images are so common that they are (and were even during Shakespeare’s time) mere tropes and clichés, which—like all tropes and cliches—become meaningless through vain repetition.

Let me slip momentarily here from the role of literature professor to that of writing professor. One of the first rules of good writing is to avoid clichés. Why is that so? Because clichés are fillers for actual thought. Clichés convey truth, to be sure (that’s why they are clichés), but they prevent thought rather than provoke it – in both the writer and the reader. If you want to communicate that someone is beautiful without really having to think about what makes the person beautiful – or to truly see what is beautiful – then you can simply grab the closest cliché (or two or three). “Her eyes are bright as the sun” … “Her cheeks are rosy” … “Her breath is like perfume.” Easy peasy. You can express the idea without giving it a thought. This business of not giving it a thought is why clichés in general (not just ones about beauty) are to be avoided. (It’s harder than you think!) Clichés are shortcuts to thinking—which is what makes them so tempting and so easy to use.

Now, this sonnet isn’t getting into all that, not directly anyway. What it is doing is mocking the conventional imagery used in love poetry because of this larger truth about clichés. But it’s also doing something much more meaningful and profound, too. And, of course, this profundity comes home in the couplet.

After making clear that the mistress is a normal woman (probably even beautiful—the poem doesn’t say she isn’t, only that her beauty is not that of the sun or roses, etc.), the speaker says his love3 is as rare as any she declares falsely4 by basing it on false comparisons. What false comparisons? Well, the ones that are so prevalent in the stereotypical similes and metaphors common in traditional romantic poetry.

The speaker’s love is rare because it is grounded in reality—in seeing the beloved for who she really is, rather than through the lens of romantic tropes. (No one wants to be understood as someone playing a part, or being a type. We all want to be seen and known for who we are in our uniqueness. This is true in all our relationships, not just romantic ones.)

I mentioned last week how transformative it was for me as a college sophomore to read Gustave Flaubert’s anti-Romantic novel, Madame Bovary. The novel’s heroine, Emma Bovary, has her head filled early in life with romantic images and ideas that come from novels (bad ones, of course, not good ones like Flaubert’s!). These false illusions about what life and love are like leave her completely unprepared to deal with life as it is. She thus chooses poorly in getting married and then compounds that bad choice with many others until her life ends in tragedy.

David Roberts commented on last week’s post then offered a note that asks an excellent question that gets at this problem of romanticism/idealism that can set us up for (or at least contribute to) failure as a result of unrealistic expectations:

This is actually the profound idea that Shakespeare is subtly, wittily, and humorously nudging us toward in this sonnet: how much truer (and rarer) is love which loves based on what is real rather than what is overblown, gussied up, inflated, and aggrandized? How much sweeter to be seen—truly seen—and loved anyway?

***

Next up:

We will cover one more of Shakespeare’s sonnets: 138.

Then we will have a follow-up guest essay by our friend Jack Heller about his experiences teaching Shakespeare in prison. I cannot wait to read it!

Then the next reading will be Christopher Marlowe’s The Tragical History of Dr. Faustus. It is online here, and you can also buy a print copy for just a few bucks here. I will plan on spending a few weeks on this play, but it’s not a long read. I truly hope you will read along. This is one of my favorite plays to teach!

***

A note to new readers (and old readers are just as welcome to note!): I have had quite a few new subscribers in the past week or two. First, welcome! I’m so glad you are here. My newsletters are free (I really want as many people as possible to share in my love of good literature!), but paid subscriptions do support this work so that others who can’t pay can benefit. Group discounts (two or more) are available as well. Paid subscribers are able to comment (and I really love our discussions), so that’s one more way you can contribute to this little community. Another way you can support my work is to share these posts with others through social media or personal contacts. Thank you for being part of it in whatever way you can!

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

Wires were often part of the elaborate headdresses women wore, so this line is pointing out, not that the mistress’ hair is wiry, but rather that it is black rather than the more esteemed (and stereotypical) blond. In fact, this is one of the sonnets within the series about the Dark Lady. Likewise, the word “reeks” in line 8 does not have the negative connotations it does today. At this time it simply refers to breath, exhalation, or emanation. The same is true of “tread” — we have that gentler sense that was in Shakespeare’s time in the expression “tread lightly.” Language is fun.

Note that this construction makes two meanings possible: “my love” could mean his feeling for her and this person who is his love. Both meanings work, but I think the first is the stronger interpretation within the context of the entirety of the poem.

I really love the word the sonnet uses, “belies.” It’s such a great word that does so much work. It means, essentially, “give the lie to,” which doesn’t necessarily mean an intentional lie, it’s important to note, but that contradicts or disguises or portrays falsely.

Also, thanks to Matt Franck for kindly pointing out to me that it’s not my gander that’s up but my dander! 😂 I will edit it later.

But really, what’s good for the goose is good for the gander!

This sonnet makes me think of both my parents and my late maternal grandparents. Neither my grandmother nor my mother were conventionally beautiful in their youth. My mother describes herself as "plain". My grandmother used to console my mother lamenting her lack of looks by saying, "Some of the plainest girls get some of the handsomest husbands." It was true for both of them, as my grandfather and my father were very handsome according to conventional standards. My mother loves to recount how when my father first paid her compliments, he said he liked a facial feature that she had thought was completely unattractive. My grandfather, on meeting my grandmother at a dinner, is rumoured to have stared so long and hard at her that she finally kicked him under the table (the rumour is entirely believable - my grandfather had intense blue eyes that stare from every photograph we have of him and my grandmother had gumption and a wicked sense of humour). My grandparents were happily married for nearly six decades until my grandfather's death, and my parents are rapidly approaching the five decade mark.

When I read that passage in Proverbs 5:15-19, "Rejoice with the wife of thy youth", I think of their examples. That is why the incel movement and similar movements (i.e. certain social media influencers) within younger male circles are so horrifying to women of mine and the next generation . The misguided males in these circles are so obsessed with imaginary standards of sexual attractiveness that they cannot see what men of former generation, such as my father and grandfather saw, that you will find all the beauty you desire in the woman you commit to love and cherish for life. If you aren't willing to lay your ideals and your ego down to cherish a real woman, then you cannot expect any woman to risk her life with you.