Here we are at the end of Paradise Lost. I feel so much pressure about how to write about this last installment in our long, slow journey together.

The fact that Milton covers nearly the entire historical narrative of the Bible in these last two books of the epic doesn’t make the task any easier! (By the way, C. S. Lewis was not a fan of Books 11 and 12, calling the history Milton outlines in them “an untransmuted lump of futurity.”1)

But, perhaps it does make my task a bit easier because I have decided in this last essay in the series to focus more closely on the poetry, the form, of Book 12 (or some of it) rather than the ideas or content. (Lewis also says, and I think in some ways he is correct here, that Paradise Lost is not “a religious poem” as Dante’s Divine Comedy is a religious poem. Milton’s is rather, “a poetical expression of religious experience.”2) To narrow my approach even more, I will overlook Lewis’s “lump” to focus instead on some passages from the end of Book 12, some of the most famous in the work—for good reason—passages marked by poignancy and poetic power.

And we know how the story ends, of course.

But to pick up on one important theological theme (before getting to the poetic expression), let’s start when the angel Michael reveals to Adam that someday all of Earth will be Paradise and will be a “far happier place” than Eden (463-64). Adam then utters lines that express the concept of the fortunate fall:

O goodness infinite, goodness immense!

That all this good of evil shall produce,

And evil turn to good; more wonderful

Than that which by creation first brought forth

Light out of darkness! full of doubt I stand,

Whether I should repent me now of sin

By mee done and occasiond, or rejoyce

Much more, that much more good thereof shall spring,

To God more glory, more good will to Men

From God, and over wrath grace shall abound. (469-78)

The fortunate fall is captured even more concisely later in lines 586-87 when Michael assures Adam that the redeemed state is one in which Adam “shalt possess / A paradise within thee, happier far.”

We’ve discussed the fortunate fall before here at The Priory (in looking at George Herbert’s poem “Easter Wings”). Essentially, it’s the idea that redemption in Christ provides a better condition than the unfallen one. Thus as bad as the fall is, it made possible something better than we had before it.

But the fall is pretty bad. As we know.

On that note, I do want to draw our attention to the way Milton portrays the presence of wolves—false teachers, false prophets, deceivers, and any who lead the sheep astray—in the church. He takes brief biblical mentions of such predators (Matthew 7:15 and Acts 20:29) and fleshes out in ferocious verse what that looks like:

Wolves shall succeed for teachers, grievous Wolves,

Who all the sacred mysteries of Heav’n

To their own vile advantages shall turn

Of lucre3 and ambition, and the truth

With superstitions and traditions taint,

Left only in those written Records pure,

Though not but by the Spirit understood.

Then shall they seek to avail themselves of names,

Places and titles, and with these to join

Secular power, though feigning still to act

By spiritual, to themselves appropriating

The Spirit of God, promised alike and giv’n

To all Believers; and from that pretense,

Spiritual Laws by carnal power shall force

On every conscience;4 Laws which none shall find

Left them inrould, or what the Spirit within

Shall on the heart engrave. What will they then

But force the Spirit of Grace it self, and bind

His consort Libertie;5 what, but unbuild

His living Temples,6 built by Faith to stand,

Their own Faith not another’s … (508-28)

Milton alludes to a dizzying array of Bible verses here (some of which I’ve footnoted). But the righteous anger Milton achieves in his versification is stunning. Of course, he is expanding on warnings given in Scripture, just as he is alluding to many issues in his own contemporary political, social, and theological situation.

Yet, when I read these lines today, I am utterly struck by the fact that they could have been penned in 2025. (You can fill in the blanks, dear readers.7)

But this overlapping of past, present, and future makes sense because Milton (and many throughout church history) understood much in the Bible typologically. (We discussed this in a previous post on Book 5 of Paradise Lost.) As Barbara Lewalski explains in her biography of Milton regarding this final book of Paradise Lost, Adam is learning to read the future as Michael presents it typologically, or history (as it is to us now) both emblematically and typologically, as it moves “from shadowie Types to Truth” (303).8 And if you want to really see how Milton’s themes and types and emblems continue to connect well to modern questions, simply read Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (which is nothing like any of its popular culture iterations!). This work—the first science fiction novel ever written—continues to deal with the questions Milton raises (albeit it from a more skeptical posture than that of Milton) with creation, Creator, and the fallen state of humankind the Creator allowed. (And Paradise Lost appears prominently in the novel.)

After all these future events narrated in the Bible—covering Genesis to Revelation—have been revealed to Adam, he goes to Eve who has been sleeping in their bower. This is where the poetry really begins to sing to me.

In the last two books, we read of Eve—and Adam’s—deep sorrow for their sin and its consequences. Now Eve receives Adam, the poem says in line 609, “with words not sad.” With words not sad. I love this description. Eve has rallied. She isn’t exactly joyful, elated, or ecstatic. But she is not sad. This construction is not, by the way, the figure of speech called litotes—ironic understatement—that we saw in Beowulf. This is more straightforward. Eve is simply not sad.

And what has changed her perspective? Dreams from the Lord. “For God is also in sleep,” Eve says.

This I too believe. This I know. (If any of you follow me on other social media, perhaps you saw that I have been visited by visions of my mother three times—each one of increasing comfort and joy.)

Eve exhorts Adam to “lead on”:

In mee is no delay; with thee to goe,

Is to stay here; without thee here to stay,

Is to go hence unwilling; thou to mee

Art all things under Heav’n, all places thou,

Who for my wilful crime art banisht hence.

This further consolation yet secure

I carry hence; though all by mee is lost,

Such favour I unworthie am vouchsafed,

By mee the Promis’d Seed shall all restore.

The sound and melody of these lines are beautiful, hauntingly so. Assonance abounds. Alliteration also. Consonance connects sound and sense. The many monosyllables punctuate the solidity of Eve’s will.

Most importantly, Milton gives to Eve the last words spoken by a character in the poem—the promise and the comfort: “by me the promised seed shall all restore.”

What syntax. What emphasis. What simplicity. What profundity. What hope.

Adam is pleased (Milton finds that important to note) but does not speak again. It is time to leave. The angels lead the pair out of the garden, wielding the blazing sword that will guard against their ever entering this place again.

They looking back, all th’ Eastern side beheld

Of Paradise, so late thir happie seat,

Wav’d over by that flaming Brand, the Gate

With dreadful Faces throng’d and fierie Armes:

Som natural tears they drop’d, but wip’d them soon;

The World was all before them, where to choose

Thir place of rest, and Providence thir guide:

They hand in hand with wandring steps and slow,

Through Eden took thir solitarie way. (641-49)

Hand in hand with wandering steps and slow is an echo of Psalm 107:4 which describes some of God’s people as wandering “in the wilderness in a solitary way,” finding no city to dwell in (KJV). Then two verses later in the same Psalm, we read that “they cried unto the LORD in their trouble, and he delivered them out of their distresses.”

Paradise was lost. But it will be regained.9

***

Just for fun, I looked up first editions of Paradise Lost for sale. Here’s one in the U.S. for a cool two hundred thousand!

***

Zoom meeting: Friends, I am terrible at scheduling things! I realize now that I was scheduling right around Easter which can be hard for people traveling. And we also have one more Milton post from Jack Heller that will give us a fuller picture before we put Milton to bed and celebrate. So let’s try two other dates and then I will decide—I promise you! Tuesday, April 15 at 4 p.m. ET or Wednesday April 16 at 3 p.m. ET. (I actually realized the Mondays can be tougher for my schedule.)

We will begin The Pilgrim’s Progress in a few weeks, but we’ve been working hard, so I want to do a couple other things in between and I will also make up a reading schedule. I plan to spend probably four weeks on it. So get your copy now! Preferably an unabridged and non-modernized one (like the Oxford Classics edition or the Norton Critical edition).

***

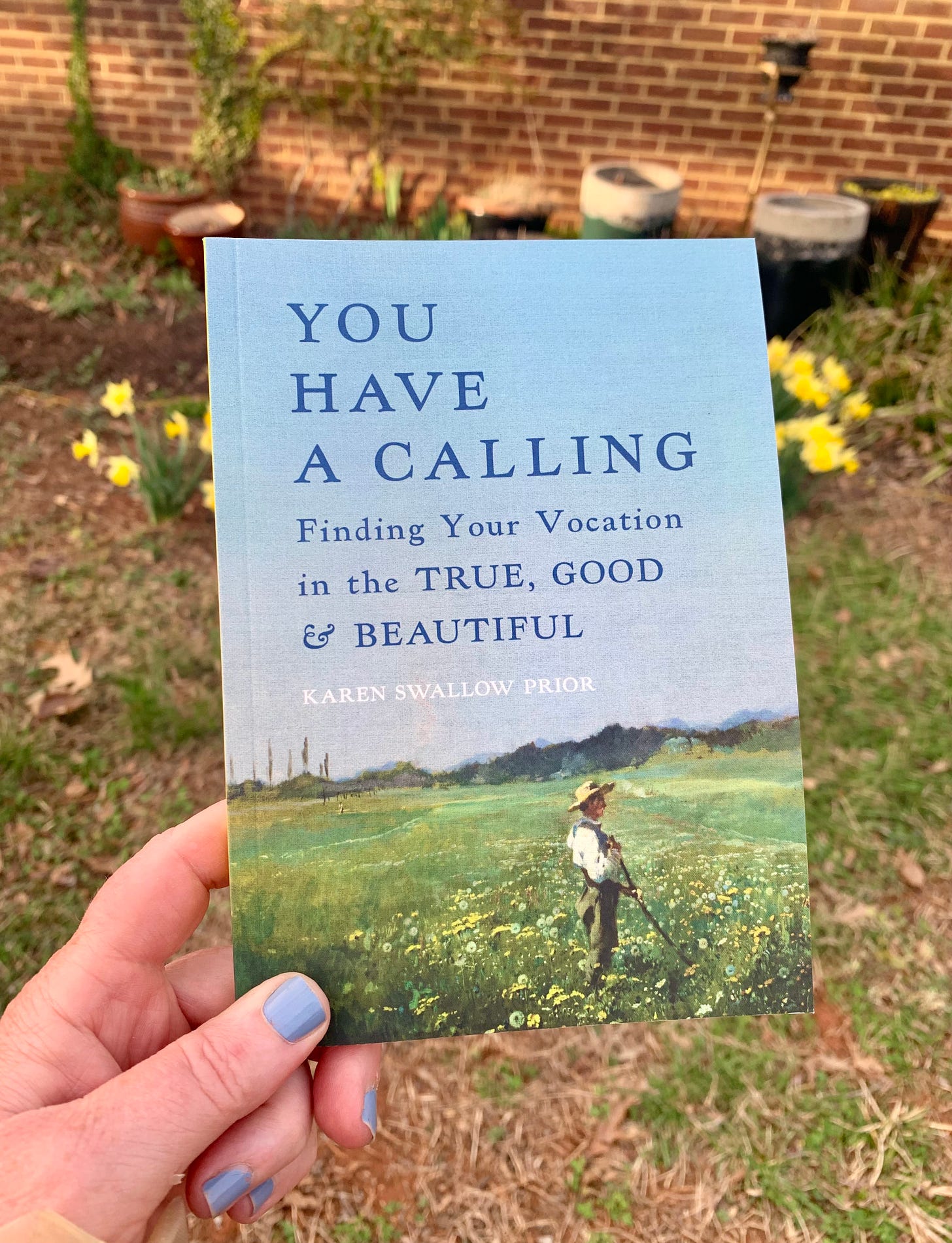

BOOK NOTE:

Please indulge me with a bit of excitement for my own forthcoming book, You Have a Calling: Finding Your Vocation in the True, Good, and Beautiful, which releases on August 5. This past week I received my Advance Reader’s Copy (which is an uncorrected proof with a mock-up cover), and I am so excited! This is my shortest (and I think sweetest) book yet. (I have always wanted a book cut smaller—those are actually more expensive to make but so nice to hold.) The actual book will be a hardcover, but it will look like this (below). And I had to take a photo of the whimsical table of contents design because I have those little drawings of tools and plants throughout the whole book. Enough about the form—now about the content! I wrote this book with people of every age and station in life in mind—from students to stay-at-home moms to all who want to know what it means to be called by God in our work. That will make it a great book for small groups, book clubs, etc., and my publisher (Brazos) is making generous discounts available for bulk purchases of ten or more books. Let me know if you want details on that!

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”10

C. S. Lewis, A Preface to Paradise Lost (Harper One, 1942), 162.

Ibid, 167,

1 Peter 5:2.

Acts 23:1.

2 Corinthians 3:17.

1 Corinthians 3:17.

Barbara K. Lewalski, The Life of John Milton (Blackwell, 2003), 486.

Milton published a follow-up work of exactly that title, Paradise Regained, in 1671.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

Reading Paradise Lost reminds me of listening to Tristan and Isolde , there are many many parts where my mind wanders and then I am caught up with transcendent beauty and I am not sure that I would have appreciated the final lines so much if I had not slogged through so many passages before.

And yes, dear writer, I did fill in the blanks …

Thank you for your guidance through this epic. So much to think about. I am in the process of writing my annual Christmas poem as well as compiling about 300 others. I have learned much about poetry from this series - how poetry circles the truth and provides avenues into truth even while entrancing us with the delight of words and rhythm. In my poem God’s angel who is commissioned to announce the birth of Christ searches for just the right people to whom to deliver this message. It turns out is has to be only the shepherds who would intrinsically understand Christ’s role as the good shepherd.