[from The Temple. Printed for Thom. Buck and Roger Daniel at Cambridge University: 1633]

“Easter Wings” is perhaps Herbert’s most famous shape poem. How could it not be? Once seen, its form forever imprints itself in the mind. But the poem is more than just its shape. As we saw with “The Altar,” the meter, rhyme, and line lengths reinforce through sense (or meaning) the sight of the poem.

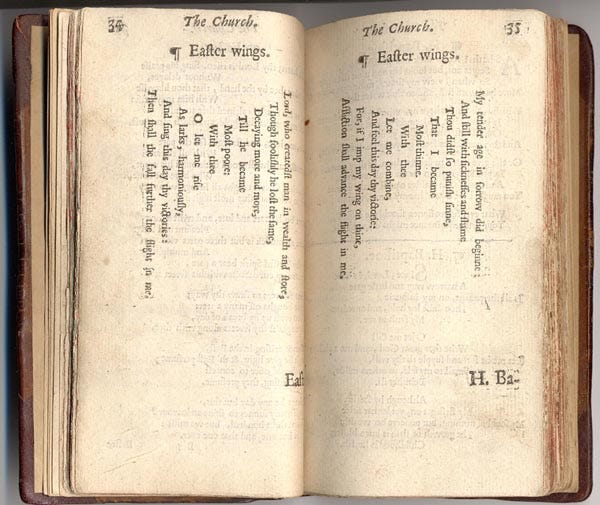

I’ve included a photo, above, of how the poem first appeared when printed: sideways so that the words are shaped like wings—some say the wings of a bird in flight (the poem mentions the lark, specifically); I say it looks like a butterfly (which also invokes the idea of transformation). Arranged upside right (as it generally appears today), the poem takes the shape of two hour glasses, one atop the other, which also is an apt image given that “time flies,” as we often put it metaphorically.

Each stanza uses the simple, and regular rhyme scheme of ABABACCDC. Yet, as you can see (and hear), the number of beats in each line diminishes and expands, then diminishes and expands again. The marvelous thing, of course, is that what each line says in words corresponds to what is happening in this lessening and growing.

Listen (as I read or you do yourself):

Lord, who createdst man in wealth and store,

Though foolishly he lost the same,

Decaying more and more,

Till he became

Most poore:

With thee

O let me rise

As larks, harmoniously,

And sing this day thy victories:

Then shall the fall further the flight in me.

My tender age in sorrow did beginne

And still with sicknesses and shame.

Thou didst so punish sinne,

That I became

Most thinne.

With thee

Let me combine,

And feel thy victorie:

For, if I imp my wing on thine,

Affliction shall advance the flight in me.The poem opens with the acknowledgement that it is a prayer, one addressed to the Lord. Notice that Herbert echoes the idea he expresses in “The Pulley” in opening the poem on the note of humanity’s creation being accompanied by the “wealth and store” of abundant blessings.

Death and decay entered the world with sin, and we became “most poore.” At this point, the poem makes clear that it is a prayer of petition, a petition to God": “O let me rise” with thee! Rise as larks rise and sing.

“The fall” refers to the fall of humanity through sin. But notice that the poem says that it is the fall that will “further the flight in me.” How can we fly higher because of the very thing that brought us down? As I mentioned in an earlier post, this is an allusion to the doctrine of the “fortunate fall” (“felix culpa” in Latin). It expresses the idea (one that Milton also illustrates in Paradise Lost) that our fall is “happy” because being saved by Christ’s death is better for us (and for God’s own glory) than our condition before the fall.

Redemption is better than perfection.

Sit on that thought for a moment because I think many of us hardly believe that (or don’t believe it at all). We would rather be perfect, independent, not in need or reliant on salvation and redemption, wouldn’t we? But the doctrine of the fortunate fall says otherwise. It says that being glorified by Christ is better than not having ever fallen at all.

Redemption is better than perfection.

Do you believe it?

Readers, I am writing this reflection on the poem during a difficult time. My mother has a condition (not yet precisely diagnosed) that has prevented her from being able to eat or hold much food down at all for several weeks. She is, essentially, starving. It is excruciating to witness. We are hoping and praying the condition can be repaired. We don’t yet know. In the meantime, she is safe, stable, and being cared for in the hospital.

Readers, she is “most thinne.”

Seeing her this way makes this poem at this particular time all the more resonant, poignant, and powerful for me. We all feel so helpless. We are all stretched, exhausted, and sad right now.

May we “combine with thee,” dear Lord.

“If I imp my wing on thine,” the poet muses. To “imp,” according to the Google search definition means to “repair a damaged feather in (the wing or tail of a trained hawk) by attaching part of a new feather.” Let me, my mother, my father, my family, and all those in our circle of love “imp” our wings on his.

If we imp our wing on his, the affliction (oh, there are so many, many afflictions in this fallen world, aren’t there?) will advance our flight. We will fly higher, better, stronger, longer, truer in him. Not despite our affliction. But because of it.

This week’s reflection is short, dear readers, as my time has been and will be short in coming days while my family pulls together.

It is hard. (Please pray for us.)

But we have wings.

Oh, and let’s not forget the most obvious thing of all about this poem: its title. These aren’t just any wings. They are resurrection wings.

We will rise again, as larks, harmoniously.

"Imp my wing" reminds me of the Isaiah 40:31 passage: "They that wait upon the Lord shall renew their strength, they shall mount up with wings like eagles", which I recently used in my post on Corvid birds. To know that use of imp, Herbert must have had some knowledge of birds - I wonder if he was a birdwatcher in his little country parish.

Praying, Karen. Earlier this year I was having a hard time swallowing and for weeks at a time I was always a bit hungry because I couldn't get enough food down. It got worse the more tired I was and it could be quite painful. All studies showed nothing but a little inflammation. I am currently on medication to reduce acid reflux, and so far, the problem hasn't gotten as bad as it was.

I've just come across this poem again, second time this week, in the book Word Made Fresh by Abram Van Engen and the line 'Most thinne' struck me as possibly playing a dual role - if one n was dropped it would read 'most thine'. Scanned quickly it almost reads that way. When we are most thinne are we also, in fact, 'most thine', most held in the safest of arms and the surest of loves? Experience may well suggest, if not immediately then in retrospect, that the answer is a blessed, astonished Yes.