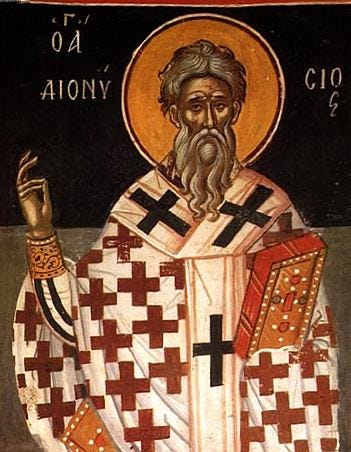

[Pope Dionysius of Alexandria: http://days.pravoslavie.ru/Images/ii617&1756.htm, public domain]

In a comment on last week’s installment on John Milton’s Areopagitica,1 Charlie asked: if licensing was required for publication, how did Areopagitica get printed in the first place?

This was such a good question! I thought at first I could give a simple answer, but in trying to answer, one thing led to another, and soon I was down a rabbit trail that I wanted to take you, my readers, on too.

So, let’s go!

First, it is this background—licensing, English Civil Wars, executions, beheadings, and whatnot—that resulted in many works of these times (particularly those of political or religious nature) being published anonymously.

But as we can see from the image of the original pamphlet as published (which I included in last week’s post), the name of the author, John Milton, was included front and center on the title page in a rather large font. Milton wrote and printed this work—unlicensed—as an act of protest. One might even anachronistically call it an act of civil disobedience. I am not sure how great the risk was for Milton in doing this, given his prominence and position. On the other hand, the king himself would soon be beheaded, so clearly all risks were pretty high during these days.

It wasn’t only authors who were required to obtain a license. According to the First Amendment Center at Middle Tennessee State University, “Printers were licensed through the printer’s guild, the London Stationer’s Company, which was chartered in 1557 and given authority to conduct searches and seizures, confiscate unlicensed works, and promulgate its own regulations.” However, “enforcement of printing laws was erratic” and often used as a political weapon.2 Surprise, surprise.

So while Milton made his authorship of the treatise public, the printer of his pamphlet was not revealed.

And in looking into this entire question (in order to answer Charlie’s question), I stumbled upon a fascinating development: it was just a few years ago that researchers were able to identify the likely printer of Areopagitica.

This discovery is in itself an amazing story.

An “interdisciplinary team of literary scholars, statisticians and computer scientists from Carnegie Mellon University” analyzed “distinctive and damaged type pieces from 100 pamphlets from the 1640s” to identify the London printers who likely produced Areopagitica.

The team used computer vision, historical optical character recognition (OCR) and old-fashioned historical sleuthing to identify the printers. Like a fingerprint, damaged pieces of metal type create unique stamps. Since typesets belonged to specific printers, impressions of damaged type can help identify a book's printers. By using statistical approaches to group many similar letters together, the team was able to compare type impressions more efficiently than prior methods have allowed.3

These printers would have been joining Milton’s protest through their act of illegal printing. The researchers who identified them attribute several other works concerning religious liberty to the same source.4

To return to the work itself, Milton was clearly making his argument for a free press on religious—Christian—grounds.

Milton cites “the examples of Moses, Daniel, and Paul, who were skilful in all the learning of the Egyptians, Chaldeans, and Greeks, which could not probably be without reading their books” and Paul “who thought it no defilement to insert into Holy Scripture the sentences of three Greek poets.”5

He then cites as a negative example Julian the Apostate, the Roman emperor who earned his name for decisively rejecting Christianity and trying to purge the faith from the empire through an authoritative reign intended to restore his vision of a lost Roman ideal (in other words, to “make Rome great again”). Julian, Milton writes, forbade Christians from studying “heathen literature” because doing so would make Christians less able “to wound us [the Romans] with our own weapons.” Such censorship, Milton argues, put Christians in “so much in danger to decline into all ignorance.”6

In contrast to Julian, Milton then describes godly Dionysius of Alexandria, who debated within himself whether or not he ought to to read heretical works. Then Dionysius had “a vision sent from God” that instructed him: “Read any books whatever come to thy hands, for thou art sufficient both to judge aright and to examine each matter.”

Milton continues,

To this revelation he assented the sooner, as he confesses, because it was answerable to that of the Apostle to the Thessalonians, Prove all things, hold fast that which is good. And he might have added another remarkable saying of the same author: To the pure, all things are pure; not only meats and drinks, but all kind of knowledge whether of good or evil; the knowledge cannot defile, nor consequently the books, if the will and conscience be not defiled.

For books are as meats and viands are; some of good, some of evil substance; and yet God, in that unapocryphal vision, said without exception, Rise, Peter, kill and eat, leaving the choice to each man’s discretion. Wholesome meats to a vitiated stomach differ little or nothing from unwholesome; and best books to a naughty mind are not unappliable to occasions of evil. Bad meats will scarce breed good nourishment in the healthiest concoction; but herein the difference is of bad books, that they to a discreet and judicious reader serve in many respects to discover, to confute, to forewarn, and to illustrate.7

Milton is comparing the truth of the apocryphal vision (Dionysius’s) with those that are recorded in the Bible by Paul to draw a parallel between books and meat.

Milton’s argument grows only fiercer and more breathtaking from here, as we will see in the next couple of weeks.

I hope you enjoy, as I am, that we are taking this reading slowly. I hope to help you come to respect Milton before we turn to his poetry. Then I hope to make you fall in love with him.

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”8

https://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/milton-and-freedom-of-speech

John Milton's Freedom of the Press Pamphlet Printers Found - News - Carnegie Mellon University

John Milton's Freedom of the Press Pamphlet Printers Found - News - Carnegie Mellon University

Milton, John. Areopagitica and Other Political Writings. (Liberty Fund: 1999), 14.

Ibid, 14.

Ibid, 14-15.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

A historical footnote that might be useful: The historian Milton calls Socrates is not to be confused with the ancient pagan Greek philosopher of the same name. Socrates of Constantinople, or Socrates Scholasticus as he is surnamed, was a 5th century (A.D.) Greek Christian historian, who recorded the years of church history from 309-439 A.D. He wasn't afraid of the ugly truth - it is from his history that we get the horrifying account of the death of the pagan scholar Hypatia at the hands of a Christian mob in Alexandria, the culmination of a bloody political struggle between the Christian and Jewish factions in the city.

On Paul's quotations of pagan poets and philosophers: The quotation Paul uses during his sermon on the Areopagus (Mar's Hill) in Athens - "For we also our his offspring" - comes from ancient Greek poems to Zeus, including 'Phaenomena' by Aratus of Soli in the 3rd century B.C. Yet Paul clearly didn't think he was in danger of confusing his audience about which God he was talking about. In the Christian fundamentalist world I half grew up in, there was always someone getting upset about supposed pagan connections in Christmas or Easter (connections for which there is the flimsiest of evidence), spoiling our innocent joy in them. Perhaps a wider study of the pagans to whom the early Church preached would have prevented those continual misunderstandings.

Thank you, Karen, for diving in on my question. It's fascinating to see the research that's been done to uncover the identities of Milton's printers, but what's even more interesting for Christians is to see yet another example of a man of faith taking serious personal risks to push against what he saw to be unjust laws. There's much more to John Milton's life story than I had realized.