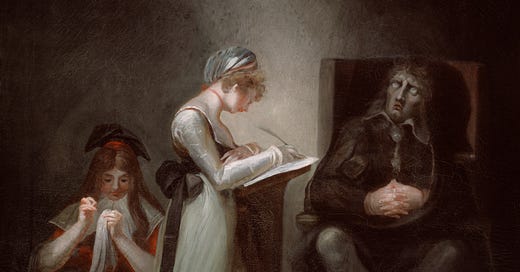

[Milton Dictating to His Daughter by Henry Fuseli, 1794; https://api.artic.edu/api/v1/artworks/44739/manifest.js]

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”1

After experiencing years of decline in his eyesight, John Milton was blind by 1652 when he was 43. He had by then already written volumes of works in both poetry and prose (including Areopagitica in 1644). But many more works, including Paradise Lost, were yet to come. Following his blindness, Milton dictated his works to scribes, often family members and most frequently his daughters. It is nearly incomprehensible to my feeble mind to imagine writing—and writing such masterpieces of poetry—this way. (Or even the usual way, haha!) But Milton was master of Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Italian, and English, and he was undoubtedly a genius’s genius.

Scholars date the writing of the sonnet we are looking at today to this period when Milton was facing the complete loss of sight, although the poem was not published until 1673. It has been numbered as Sonnet 16 and 19 but is often called by a later title Milton never used, “On His Blindness,” for reasons apparent in the poem (although that word is never mentioned). Alternatively, it is sometimes referred to by its first line, “When I Consider How my Light is Spent.”

The poem is an Italian (Petrarchan) sonnet, a form we have discussed previously at The Priory. As a reminder, this form is divided into two major parts, an octave and a sestet, with a corresponding rhyme scheme (in this case) of ABBA, ABBA, CDE, CDE.

One particular quality of Milton’s approach to the sonnet form—which we will also see in Paradise Lost—is his use of enjambment. Enjambment in poetry occurs when the sentence, clause, or syntax of a line runs over into the next. (Enjambment is a stark reminder that poetry should always be read in a way that follows the punctuation and meaning of the lines, and not with pauses at the end of a line just because it is the end of the line.)

One other point to note before reading (or hearing) this poem is Milton’s brilliant interruption of the Italian sonnet form in line 8. I noted that this form consists of an octave and a sestet. But when we consider the meaning of the lines that follow (and the enjambment Milton uses) we will see that the turn in thought that usually begins with the sestet actually begins half a line earlier when “Patience” replies to the speaker’s fond (or foolish) question “soon” (or quickly) in order “to prevent that murmur.”

Let’s read it now with that in mind:

When I consider how my light is spent,

Ere half my days, in this dark world and wide,

And that one Talent which is death to hide

Lodged with me useless, though my Soul more bent

To serve therewith my Maker, and present

My true account, lest he returning chide;

“Doth God exact day-labour, light denied?”

I fondly ask. But Patience, to prevent

That murmur, soon replies, “God doth not need

Either man’s work or his own gifts; who best

Bear his mild yoke, they serve him best. His state

Is Kingly. Thousands at his bidding speed

And post o’er Land and Ocean without rest:

They also serve who only stand and wait.”

That last line— “They also serve who only stand and wait”—is famous (in case it sounds familiar, and you can’t place it). These words are part of the speech narrated in the poem as given by Patience (personified) in answer to the speaker’s fearful question. Many see an allusion here to the story of Mary and Martha from the Gospel of Luke which finds busy Martha complaining that she is doing all the work in preparation to serve the visiting Christ while Mary sits at his feet listening to him. Milton turns Mary’s sitting to standing, however, which has evocative implications, readiness for Christ being one of them.

“They also serve who only stand and wait”: what a beautiful and needed biblical truth for one lamenting the loss of his “light” at midlife. One who is worried that he has buried his talent in the ground like the wicked servant in the parable told by Jesus in Matthew 25 whose master casts him into outer darkness for his sloth. One who professes his soul’s desire to serve God well yet cannot help but wonder if God will require the same results from him despite the loss of his “light” (eyesight). One filled with fear, trembling, and anxiety.

One who is like all of us, I suspect.

And yet, the poem suddenly shifts toward resolution—and comfort—when Patience (personified) replies with one of the most profound and essential of all doctrinal truths: God does not need our works or our gifts.

We serve God best by bearing whatever yoke he gives us. Like a king who commands all power, all dominion, and all authority, God needs nothing. Some serve him by hastening to do his will here and there and everywhere. And some serve him by simply waiting, waiting for his call.

(Calling, by the way, is the subject of my next book! Stay tuned for more on that.)

After Christmas, we will begin our slow journey through Paradise Lost. The poem is divided into 12 books, and in the Penguin edition I’m using, each book is around 20 pages. You can also read it online here. I think it will be a good challenge—a practice, a discipline (and hopefully a pleasure)—to try to read this much (this little?) poetry each week. It will be for me, too! So I encourage you to give it a try. If you are a New Year’s Resolution kind of person, then this might be your resolution!

BOOK NOTE:

It is nearly Christmas, but it’s not too late to get books for the classic literature lovers in your life!

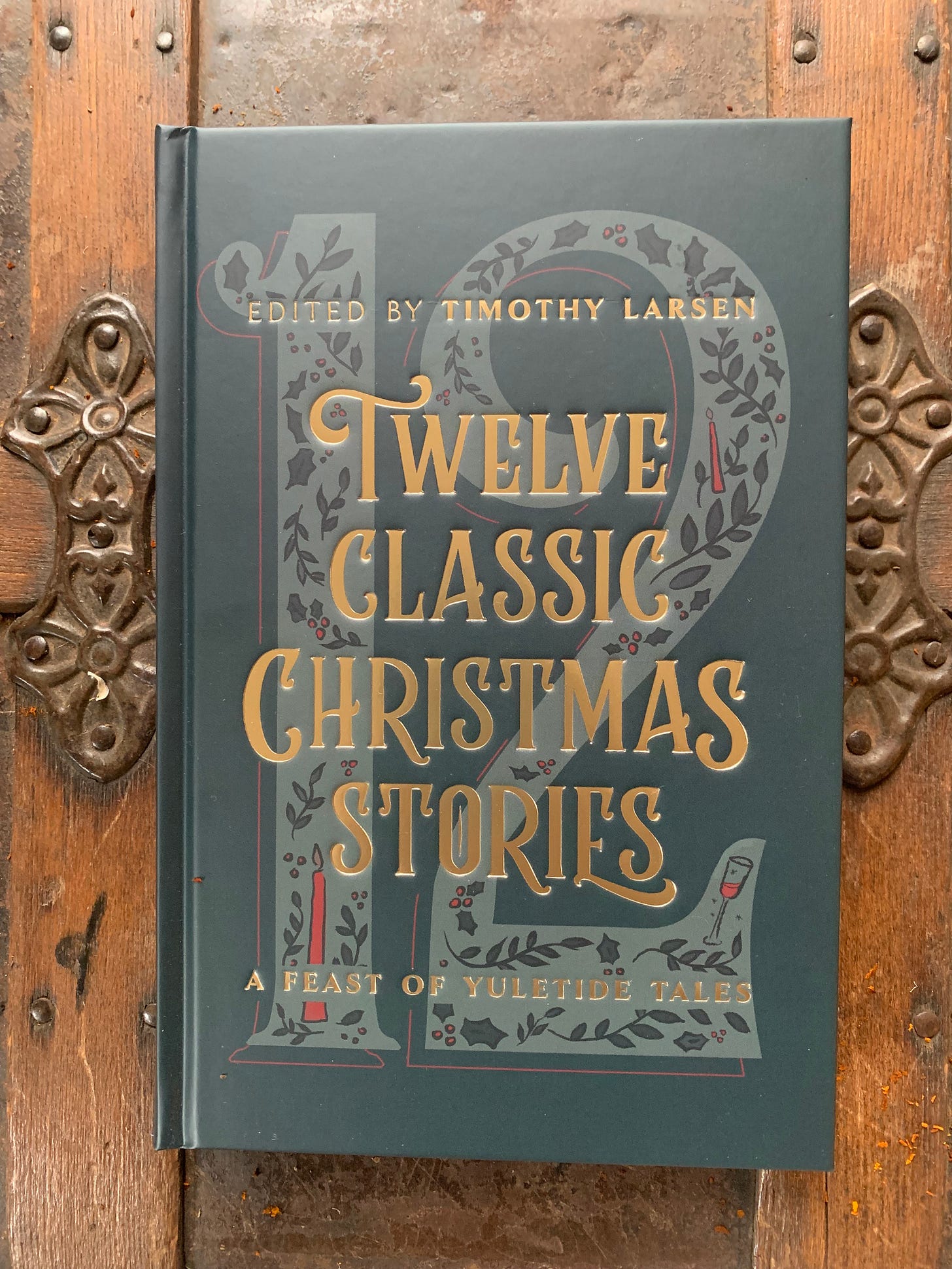

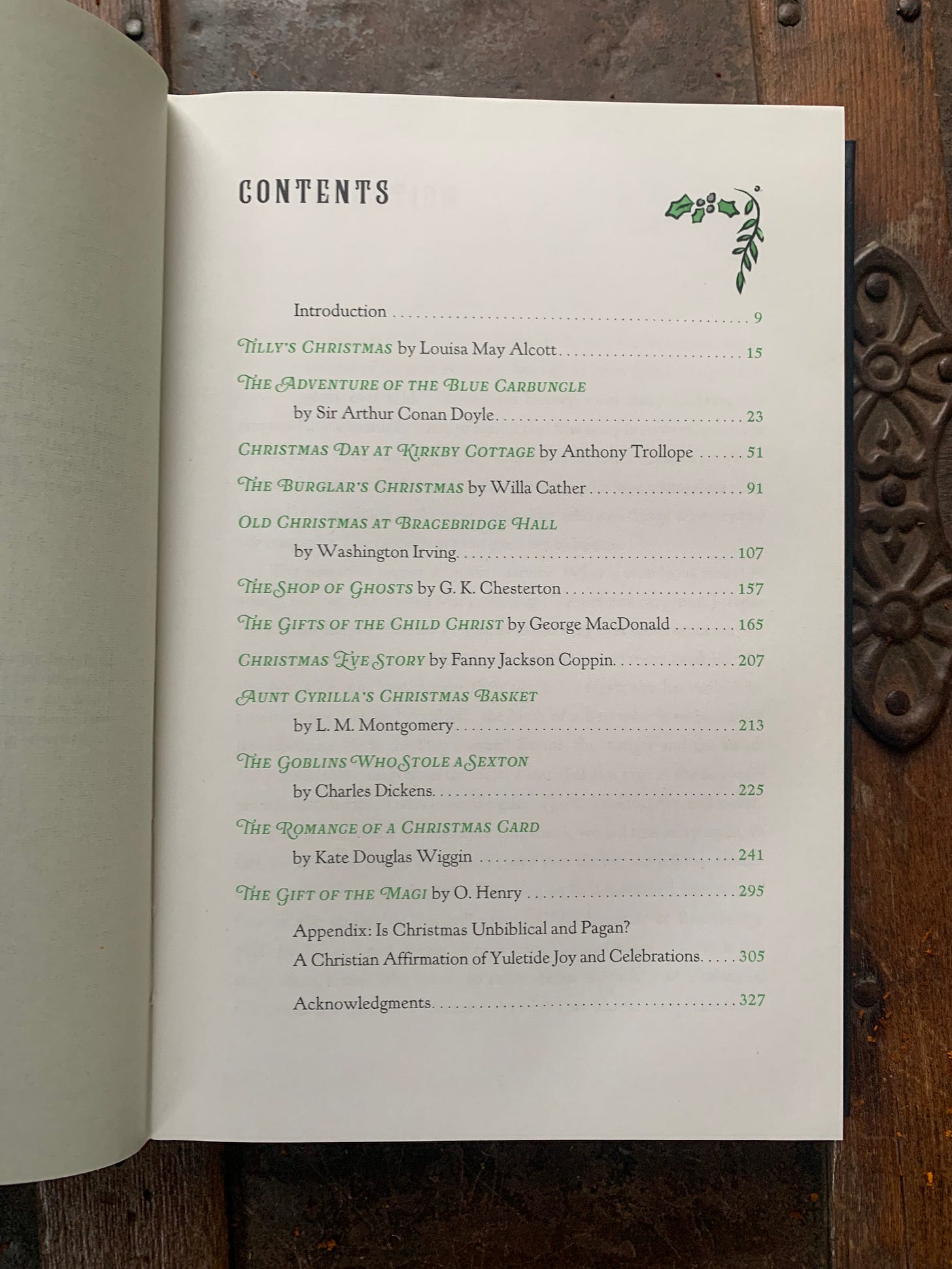

First let me commend (and recommend) this beautiful volume of Christmas classics suitable for the entire family. It is a collection edited by Timothy Larsen, Twelve Classic Christmas Stories. The physical book is simply gorgeous, and the tales inside are the kind you can return to again and again.

And I’d also like to suggest the set of classics I’ve lovingly edited, annotated and bound for the book lover in your life (even if that’s you!). These volumes feature creamy paper, readable font, wide margins, and a sewn-in bookmark.They are available singly through most booksellers and as a set from my publisher: Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles, Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

The last line "They also serve who only stand and wait", was used in WWII to encourage not only those waiting at home, but also those serving in other capacities than on the frontline. Which reminds me of one of the most difficult and rewarding experiences of my student days:

When I was still a very rookie nursing student, I was given the responsibility one day to care for a patient who had a reputation for being difficult. At first, it was terrible for me, who am naturally quiet and unassertive, trying to persuade the patient to cooperate with what needed to be done. I had to take the patient to an appointment. We had to wait a while, and the patient tried to tell me that I was wasting my time staying with him. I assured him that I wasn't. After a while, he looked at me standing by his wheelchair, and said he had remembered a saying from the Second World War, "They also serve who stand and wait." Then he began to tell me his wartime experiences. At the end of the day, when I said goodbye to the patient, he was quite cordial, saying it had been a pleasure. I have often remembered his words, as I have done a lot of standing and waiting over the years, for one reason and another.

Thank you, Karen for choosing this poem. Milton is describing something universal for those who live long enough to experience the teacher of humility that is aging. I have a comparitively mild neurological condition that is chipping away at things I used to be able to do. As I watch friends age or I grieve my own loss of abilities, this poem reminds me that i can wait and pray, and find new opportunitiesto serve at The King's pleasure.