[A portrait of Donne as a young man, c. 1595, in the National Portrait Gallery, London; image in public domain]

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”1

John Donne is one of the most brilliant poets you will ever read. I pray I can do him justice as we embark on this series reading some of his poetry together. Even if not, I pray I can help you fall in love with (or more in love, as the case may be) his wit, his humanity, and his God.

Donne was born in London in 1571 (or 1572), into a prosperous, devout Roman Catholic family during the years in which the English Reformation was still solidifying. To be a Catholic in such a time, when anti-Catholic laws and sentiments prevailed, was to be marginalized, to say the least, politically and socially. Some in Donne’s immediate family were even persecuted because of their ties to the Catholic church.

Donne entered the Church of England sometime in the 1590’s, probably for political and theological reasons, but sabotaged his likely political appointments when he secretly married his employer’s young niece, Ann. Ann’s wealthy father had Donne imprisoned briefly, and Donne lost his job. He and Ann struggled financially for many years as a result of his unemployment, a situation made more dire because the two had twelve children by the time Ann died in 1617 at age 33. Donne loved his wife deeply, writing his most sensuous, erotic love poems to her. His sweetest, shortest poem (really an epigram) on this subject is this:

John Donne, Ann Donne, Undone.

Donne served in Parliament but was pressured by King James I to take holy orders. In 1615, Donne was ordained as a priest in the Church of England and served as a chaplain in the royal court. He finally gained an appointment as rector for two parishes and held these posts for the rest of his life. His writing turned almost completely to religious devotion, and he wrote spiritual poems, sermons, and meditations until he died in 1631.

Although most of his poetry was unpublished in his lifetime (as was often the case) it circulated, along with his sermons and prose works, in the form of manuscripts. He was known during his life as a gifted preacher, and his literary reputation has only increased over the ensuing centuries.

Donne is foremost within the school of poetry known as the metaphysical poets, a group of seventeenth-century poets who wrote about spiritual, eternal, transcendent concerns by presenting them in material, finite, earthly terms. The metaphysical poets, especially Donne, approach their subjects through rational discussion—sometimes, seemingly, to the extreme. But there is a method to such madness, as such use of reason can serve, paradoxically, to demonstrate the limits of reason, pointing to the mystical by way of the intellect. Such poetry is rather cerebral. But it’s also fun, if you are willing to meet it on its own terms: paradox, contradiction, and jarring comparisons that reveal truth through unexpected juxtaposition are the trademark of metaphysical poets.

Their poetry is often characterized by use of a device called the metaphysical conceit: an extended, elaborate metaphor that uses a witty and unexpected comparison between a lofty idea and a mundane, physical object. We will see this in action more vividly in later poems in this series, though we have a taste of it in “Batter My Heart, Three-Person’d God.”

Aside from all these qualities, Donne is particularly known for his rare ability to balance passion and reason—along with his brilliant wit.2

How can anyone not love all this?

Let’s begin, then, with “Batter My Heart.”

Batter my heart, three-person'd God, for you

As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend;

That I may rise and stand, o'erthrow me, and bend

Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new.

I, like an usurp'd town to another due,

Labor to admit you, but oh, to no end;

Reason, your viceroy in me, me should defend,

But is captiv'd, and proves weak or untrue.

Yet dearly I love you, and would be lov'd fain,

But am betroth'd unto your enemy;

Divorce me, untie or break that knot again,

Take me to you, imprison me, for I,

Except you enthrall me, never shall be free,

Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me.

We studied the sonnet form in reading the selections by Shakespeare. Donne, too, wrote sonnets. This one is from a series called the Holy Sonnets. But Donne tended to use the Italian or Petrarchan sonnet form (although sometimes he combines both forms). Whereas the Shakespearean or English sonnet is comprised of three quatrains followed by a couplet, the Petrarchan form has an octet (8 lines) followed by a sestet (6 lines). Both forms feature a turn or emphasis in thought. In the Italian sonnet, that shift occurs with (or near) the sestet. Thus when we approach a poem of this form, we should look for one main theme to be developed in the first 8 lines, then a turn in thought to take place in the second half. (But never forget that poets sometimes break the rules and when they do so they are also calling attention to something else in that break.)

In this poem, the turn in thought is clearly marked by the word, “Yet.” (So helpful, John! Thank you!) The big picture view is that the octet describes just how stubbornly the speaker resists the power of God, and yet, the sestet clarifies, dearly loves and desires him, too.

Such a summary is very reductive, of course. There is so much more happening in the poem that is worth looking at more closely, beginning with the title, which makes clear not only Donne’s belief in the doctrine of the Trinity but also the poetic device of apostrophe: the poem is an address to God.

The poem is an appeal to God, an exhortation to him to make the poet’s life new by first breaking, blowing, and burning the old man away. The sound of these verbs conveys the force the speaker knows is necessary to accomplish this: “… bend / Your force to break, blow, burn …” There is no way to say or hear these words gently or quietly. They convey in their sound and imagery what is needed to make a person new.

There is so much to the sounds in this poem, more than I can possibly cover here: alliteration (repetition of initial consonant sounds as in make and me), internal rhyme (rhyme within the line as in me and free), assonance (repetition of the initial vowel sound as in except and enthrall)—just to name a few.

What follows the opening lines is a series of comparisons which compare a spiritual condition with earthly things: The old creature is like a town taken over by enemy forces. Reason, which is the mark of God’s image in the human person (a “viceroy” or regent or stand-in) is a weak officer.

Then comes the turn in thought, along with the metaphysical conceit. This part of the poem presents the soul not turned to God as a lover—or bride-to-be—one engaged to the Enemy but who longs to be joined in union with God.

The poet pleads with God to break that bind—bring, as only a just court can, a divorce from that evil spouse. (Remember, in this age divorce was not easily or often granted—just ask King Henry VIII!)

Then the paradoxes: Unless you imprison me, I will never be free. Unless you ravish me (this is the language of consummation), I will never be chaste or pure.

The sexual imagery is, if we are reading attentively, shocking.

But then again, it is no more shocking than the picture (and reality) of a God who becomes Man in order to be the Bridegroom to a blemished and captive Bride.3

As we continue in this series, we will read:

“The Flea”

***

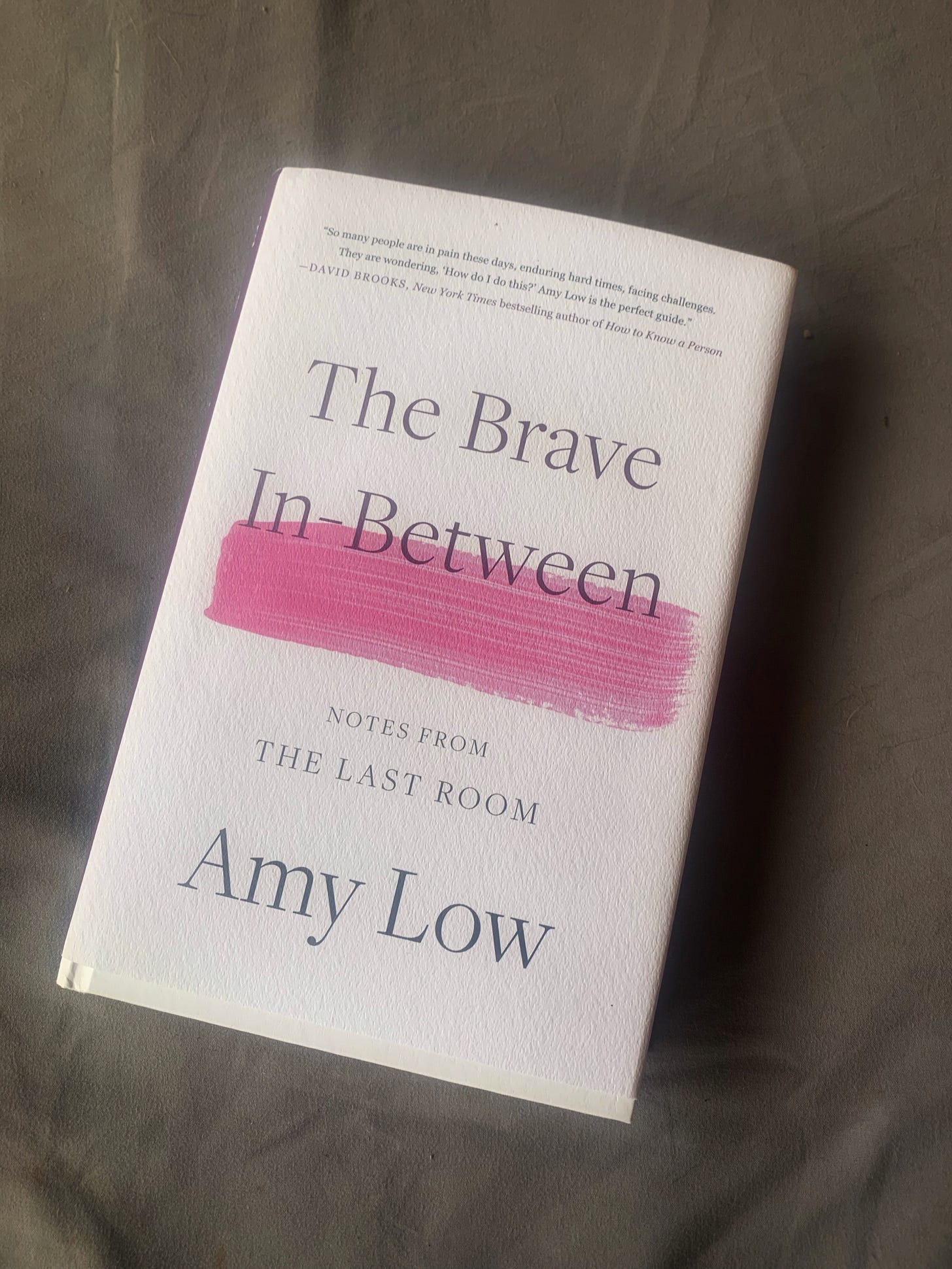

BOOK NOTE:

The Brave In-Between: Notes from the Last Room is a stunning, beautiful new book by Amy Low. I don’t know what I was expecting from a book Stage IV metastatic colon cancer, but it was not this. It is moving, funny, twist-and-turn-y, and deeply, deeply wise. Structured around Philippians 4:8, the book centers each chapter on one of these virtues: true, noble, right, pure, lovely, admirable, excellent, and praiseworthy. On her Instagram account, Amy calls her book a “beach read.” And you know what? It really is! And yet it’s so full of wisdom and beauty, you will want to read it with a pen in hand. I sure did.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

I believe I have recommended this film before, but it is worth recommending again: Wit, with the incomparable Emma Thompson, is about an English professor who specializes in John Donne and has to re-learn much as she faces terminal cancer. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0243664/

Again, a bride captive to the Enemy, not the beloved Bridegroom.

I have always loved Donne, and this poem, so much. Today I love him, and it, even more. Mission accomplished. :) The "yet" calls to mind the numerous "yet" and "but now" turns in the Bible - Job, David in the Psalms, Paul in Romans, etc. So beautiful.

Who do you think Donne sees as the enemy, Karen? Is it a personification of Sin or perhaps the Devil? My New Testament lecturer believed that Paul in Romans 7 is speaking about humanity wedded to Satan in sin . I was never convinced, certainly not from that passage, but maybe he and Donne are on the same page? I also wondered if line 6's 'Labour to admit you' was a sideways glance at Song of Songs 5:5 where the Loved's hands drip with myrrh and struggle to open the door. But perhaps that's an allusion too far.

Really looking forward to this series - the only Donne I've read is Philip Yancey's recent modern rendering of Donne's Devotions which was excellent. I didn't have any of Donne's poetry on my shelves so I've bought the Delphi Kindle edition of his poems - they do a great job and for less than $2 it's a steal.