[Vincent van Gogh, L'église d'Auvers-sur-Oise, vue du chevet; public domain]

Show me your true church, Christ.

This is the petition made in Donne’s Holy Sonnet 18.

I have taught this poem for years and when doing so, I’ve tended to treat it as a poetic treatment of an academic or even a doctrinal question.

So detached was I.

But no longer.

I return to this poem today with the realization that I am asking the Lord the same questions.

Show me dear Christ, thy spouse so bright and clear.

What! is it she which on the other shore

Goes richly painted? or which, robb'd and tore,

Laments and mourns in Germany and here?

Sleeps she a thousand, then peeps up one year?

Is she self-truth, and errs? now new, now outwore?

Doth she, and did she, and shall she evermore

On one, on seven, or on no hill appear?

Dwells she with us, or like adventuring knights

First travel we to seek, and then make love?

Betray, kind husband, thy spouse to our sights,

And let mine amorous soul court thy mild Dove,

Who is most true and pleasing to thee then

When she is embrac'd and open to most men.

Writing during a time when the Church was fracturing all around the globe, writing when he himself had turned from the church at Rome to the one at Canterbury, and when he was witnessing so many reflections of Christ’s bride being displayed in various places and ways, Donne begs Christ, “show me … thy spouse.”

Is Christ’s bride that woman “on the other shore” (France, which was primarily Roman Catholic during Donne’s lifetime, is visible from England), the one who is “richly painted”? The imagery of heavy makeup is, of course, associated with both the wealth and ornamentation of the Roman Catholic church and with harlotry. But notice that the poem is not accusatory here. The question is sincere.

So too are all the questions that follow.

Is your spouse one of those ravished and robbed—one from the Protestant church of Germany or England?1 Does the true church simply sleep for a thousand years only to awaken and emerge for one?2 Is she full of truth or error? Is she worn out by time, outdated and irrelevant, or is she ever new? Is Christ’s church on one hill, seven, or none?3 Is she already here present with us or is she only in the seeking in the way medieval knights must give chase to their lovers—in other words, is she real or ideal? Present or future?

The questions end and another petition to Christ begins the poem’s conclusion.

The speaker begs Christ to “betray” his bride by revealing her “to our sights.” This word, “betray,” is crucial to the metaphorical conceit as it continues. The speaker seeks to “court” the bride of Christ with his “amorous soul.” He wants the church. He desires her. And he uses the same marital/sexual metaphor to express the union he seeks that the Bible itself uses.

Ephesians 5:22-33, for example, describes Christ as bridegroom to the church, his bride. 2 Corinthians 11:1-4 says that Christ is the husband of all believers. And Revelation 19:7-8 and 21:9-11 also refer to the church as the bride of Christ.

Drawing from this biblical imagery, Holy Sonnet 18 is, perhaps, where Donne combines the holy and the erotic most completely--most consummately.

The last two lines of the sonnet bring the metaphor home with a stunning paradox: the “bright and clear” bride of Christ, these lines argue, is “most true and pleasing” to the Lord “when she is embraced and open to most men.” (This imagery reflects a similar paradox in the closing lines of “Batter My Heart, Three-Person’d God,” which state, “... I, / Except you enthrall me, never shall be free, / Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me.”)

To be clear, in the context of the seventeenth century church and his own life, Donne is here ecumenical not universalist (“most” men, not all). Yet within that context—a period during which men (including Donne himself) were imprisoned for being part of one church rather than the other and when others were tortured, burned at the stake, or worse—Donne’s appeal to a “promiscuous” and “open” church is as modest as it is radical.

But I think the most compelling aspect of this poem is not the character of the bride as much as it is the character of the one seeking her.

The one asking Christ to show forth his spouse is “an amorous soul.”

This phrase is part of the sexual imagery in the central metaphor. But the sexual imagery is just the comparison, not the thing being compared to it.

The “amorous soul” is not a soul burning with lust who is looking for sexual satisfaction. The speaker says of the bride that she is a “mild Dove.” The dove is a symbol, of course, of the Holy Spirit, but also of peace, purity, and love. This is what the amorous soul seeks. This is a soul who, in being drawn to beauty, is seeking the true source of all beauty—all truth, all goodness.

I have written much on the polarization and politicization that marks the church today. I lament this as I know many of my readers do as well.

And yet, let us be reminded that both within the church and without it are amorous souls, souls who desire, like Donne, like me, to see the spouse of Christ, clearly and brightly.

Witnessing Donne wrestle centuries ago with the very things I (and so many others) have been asking in recent days is revelatory, exhilarating, affirming, and chastening (there really is nothing new under the sun, is there?). It is all of these at once. So very many of us have been asking these questions. They are not original.

Yet, they are important. Like Donne, we must ask them. And like Donne, we must ask Christ to show us the answers. We must ask Christ to show us his spouse—and to refuse in the meantime to embrace her imposters.

***

Here we conclude this cycle of lessons on John Donne.

And now it’s summer break at The Priory, at least in terms of readings. Next week I will reflect on the one-year anniversary of this newsletter. Then I will continue my series on platform and publishing. You can take some time off from the reading—or better yet, catch up on anything you missed! Stay tuned for next readings in this series surveying British literature.

***

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”4

***

BOOK NOTE:

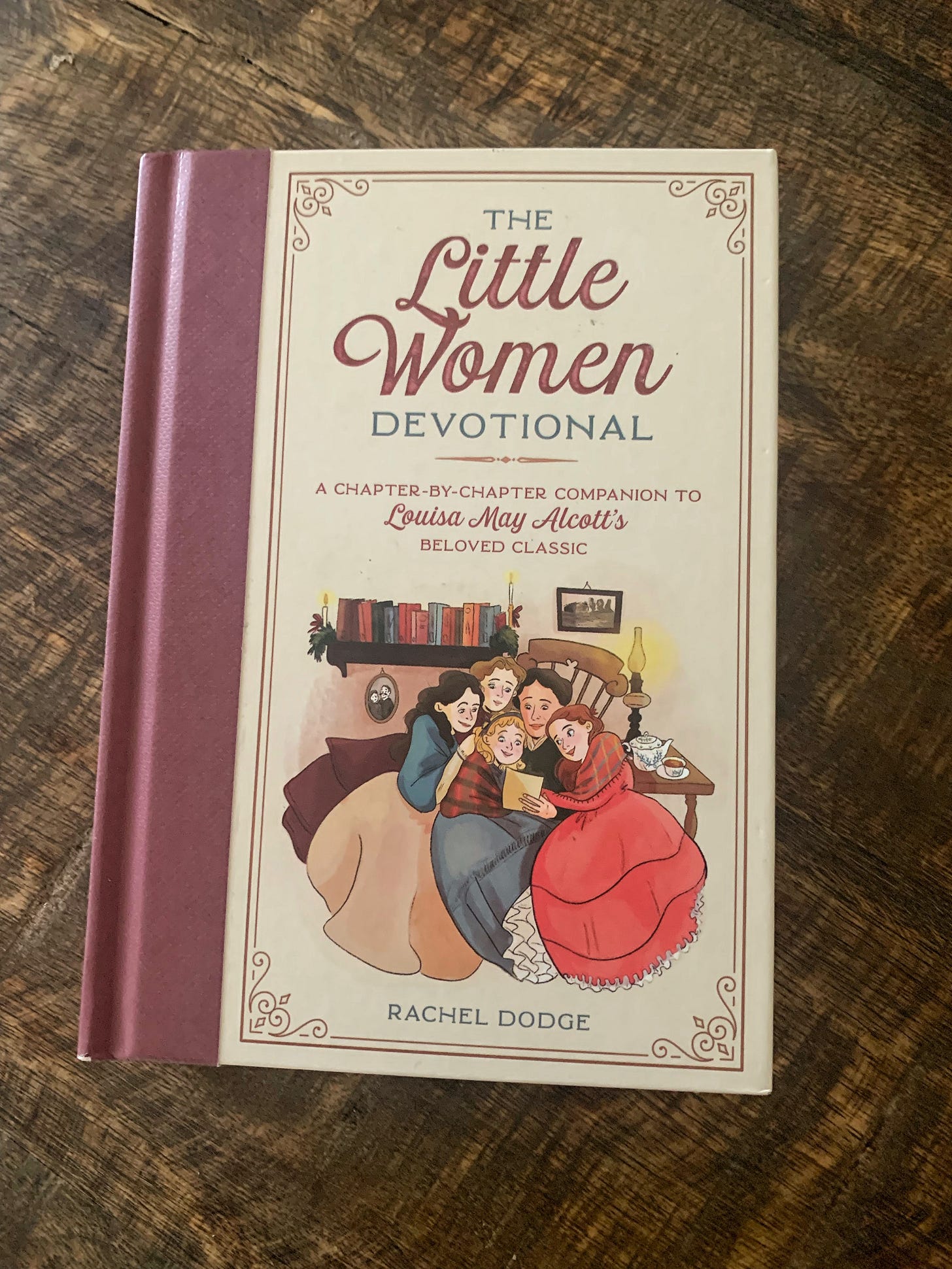

I was introduced to the work of Rachel Dodge with her lovely 2018 book, Praying with Jane: 31 Days through the Prayers of Jane Austen.

Well, a couple weeks ago I was introduced to Rachel Dodge herself when the bookstore where she works, Landmark Booksellers in Franklin, Tennessee, hosted me for a most lovely evening talk and book signing. While I was there, Rachel gave me one of the books in her series of devotionals based on classic literature.

Thank you, Rachel, for The Little Women Devotional and for your work!

The “purified” or Puritan-influenced churches were portrayed as the “virgin” to the harlot or whore in a longstanding dichotomy. This imagery became even more solidified with the ascent of Queen Elizabeth I who, in aligning herself with the Protestant Church of England and becoming the “Virgin Queen,” also took the place symbolically of the Virgin Mary so beloved in the Roman church. (This explanation is a little rough as I’m not entirely sure on this point!)

Ever feel like the church right now is largely dormant? You aren’t alone. Donne wondered, too.

In my edition of this poem in The Norton Anthology of English Literature, the editor’s footnote explains, “The church on one hill is probably Solomon’s temple on Mount Moriah, that on seven hills is the Church of Rome, that on no hill is the Presbyterian church of Geneva.”

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

Donne lived during the first half of the Thirty-Years War (1618-1648), a conflict between the Catholic and Protestant states in the Holy Roman Empire that killed about 8 million people, including an estimated 20 percent of the population in what is now Germany. Donne had been part of a diplomatic mission to the German states before being ordained. In addition, France was experiencing another stage in its ongoing conflict between Catholics and Protestant Huguenots, this time a series of Huguenot rebellions. The seige of the Huguenot stronghold La Rochelle alone killed over 20,000 people. England was directly involved with what happened, as the Duke of Buckingham*, favourite of James I and Charles I, had failed in an attempt to support the Huguenots in La Rochelle. I think the questions of Donne's poem reflect the anguish of a decent man witnessing a conflict that threatened to trap the civilization in which he lived in a cycle of death.

*The Duke of Buckingham was later assassinated by a disgruntled officer who took part in the failed expedition. The 19th century French novelist, Alexandre Dumas, pere, makes this assassination a key point in 'The Three Musketeers', imagining the officer was motivated as the result of a deeply laid plot by France's Cardinal Richelieu. It is historically true that the English government thought the officer had not acted alone but were unable to extract a confession under torture.

The call of Christ is full of paradoxes. Just this week I was reminded that the Christlike response to mockery is rejoicing, not outrage. Matt 5:12.

Donne's longing for Christ's true Bride in the midst of chaos and division made my heart ache today.