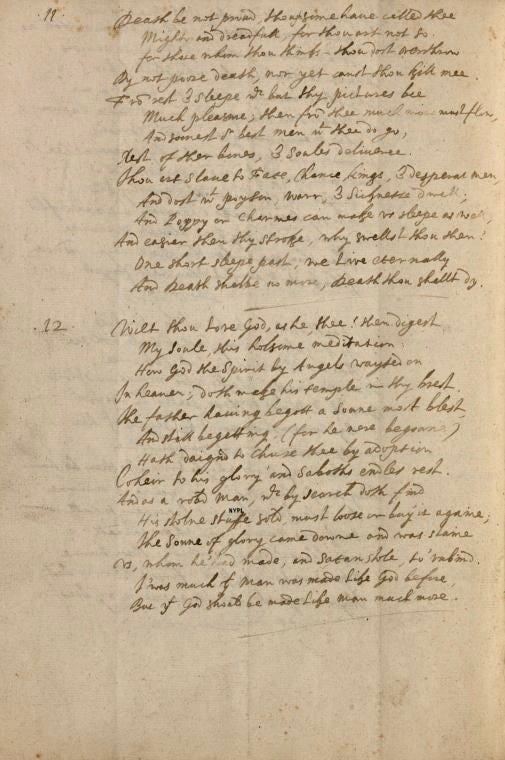

['Death be not proud' in Donne's handwriting (top half of the page) from the Westmoreland Manuscript of his works in the Berg Collection. c. 1620. From the New York Public Library]

Readers, as you know, this substack experiment has largely, among other things, been a way for me to regain a semblance of the classroom teaching experience I lost last year. I hope you don’t mind that this week, I’m going to be a bit more structured during this particular “class” and give you some strict instructions.

If we were in an actual classroom together, this is how we’d begin our discussion of Donne’s “Death, Be Not Proud.”

First, I would pull up this clip from Wit, the film adaptation of the Pulitzer Prize-winning play written by Margaret Edson (which I keep bringing up, I know). We would dim the lights and watch this five-minute clip together on the large screen at the front of the room. (Since we are setting the scene properly here, I should mention that I would fumble with the controls a bit until some kind student feeling sorry for me would come and get it going for me just before I call for IT to come to the rescue.)

Now the clip is up and it’s ready to play. So please, class, stop reading and watch this. Again, it’s just five minutes, and it makes an excellent introduction to the poem (and to metaphysical poetry more generally):

I could teach a whole class on this film (in fact, I’ve taught the play on which it’s based several times). I won’t do that here (perhaps in the future?), but may I point out several brilliant lines? These are lines which, if you’re a regular reader of this newsletter, you will likely appreciate. They are all lines spoken by Dr. Evelyn Ashford to Donne-professor-now-cancer-patient Vivian Bearing, who remembers their exchange years later as she faces her own impending death (true confession, guys, I see a lot of both Vivian Bearing and Dr. Ashford in me, and not just the nice parts):

· “Begin with the text, Miss Bearing, not with a feeling.” (Ouch!)

· “This is metaphysical poetry, not the modern novel.” (LOL!)

· “lf you go in for this sort of thing l suggest you take up Shakespeare.” (ROFL)

· “Nothing but a breath, a comma... separates life from life everlasting.” (Wow …)

· “Life, death, soul, God... past, present. Not insuperable barriers. Not semicolons. Just a comma.” (Again, wow ….)

These lines alone—and the entire film—demonstrate what can be gained and understood by reading good poetry well.

And in Donne, we have some of the best poetry ever written. To wit, “Death, Be Not Proud”:

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so;

For those whom thou think'st thou dost overthrow

Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me.

From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be,

Much pleasure; then from thee much more must flow,

And soonest our best men with thee do go,

Rest of their bones, and soul's delivery.

Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell,

And poppy or charms can make us sleep as well

And better than thy stroke; why swell'st thou then?

One short sleep past, we wake eternally

And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.

(Ironically, I know my go to source for these poems uses the semicolon. Which manuscripts and which editions are most correct and authoritative are questions not for this occasion!)

Also related to the punctuation, there is actually quite a bit of debate about the best way to read the poem, and how many and which of its metrical feet are iambic. Some of that is clearly lost in translation from 17th century British English to 21st century American English. Here is one of the better readings of the poem that I found.

This is one of those sonnets by Donne that combines the Italian and English forms. Like the traditional Italian form, its larger structure consists of an octet and sestet. Yet the rhyme scheme ends with a couplet as Shakespeare’s English sonnets did. (Note that “eternally” and “die” form an approximate rhyme—which counts as rhyme.) An emphasis in thought occurs at the beginning of the sestet, and another at the beginning of the closing couplet. On the other hand, these are really culminations of the poem’s entire argument (rather than turns in thought): Death, you have no cause to be proud.

Again, the poem takes the form of an apostrophe: an address to someone (or something) absent. In addressing death this way, death is also personified, not only through apostrophe, but also throughout the poem with the imagery that describes death as a usurper, as a thief, as one who dwells with ne’er-do-wells, and as a finite, living being destined to die--and die forever, unlike those he thinks to kill.

So much of the poem’s effect is found in the sound: not only the usual rhythm of iambic pentameter, but the sounds of the letters themselves, with much repetition within the lines and between the lines.

With almost no overly difficult vocabulary in this poem, it’s one I encourage you to read aloud—several times—for yourself. Try different emphases to hear which one conveys the meaning best. Listen to the way the harsh consonants and the long vowel sounds contribute to the firmness and confidence of the poem’s dismissal of death’s power.

In addition to sound, the poem relies heavily on irony and paradox, which of course, reach their peak in the last line with the declaration that death will die.

Before that we are presented with the ironies that:

· If sleep is a “picture” or image of death (a common trope in poetry of this time, as well as in Shakespeare), and if sleep brings us rest and the pleasure of dreams, then how much more pleasure will the real thing (death) bring us?

· When death takes the “best men” (perhaps brave warriors or other noble men), death brings rest to their bones and delivery of their souls.

· Death is the “slave” to those things that cause death: fate, chance, the rule of law (kings), and criminals (desperate men).

· Death (so haughty and proud) is but the companion of poison, war, and sickness.

· Drugs and magic spells can also make us sleep as well as death—better, actually!

· Death is but a sleeping that allows us to awake in eternity.

More than all this is the very precise point that death dies when we enter eternal life. Death ushers us into eternity. Dr. Ashford in Wit explains it best—with a breath. A mere comma.

You would be right to hear an echo in the poem of 1 Corinthians 15:55: “O death, where is thy sting? O grave, where is thy victory?” (KJV)

Death, be not proud indeed. Christ is victorious over death.

I don’t think you have to be a Christian to agree that death is one of—if not the—thing most wrong with this world. There are other reasons for my faith in Jesus. But the greatest one is that he overcame death—not just his own, but all death. In my book, such a God is worth believing in.

As we continue in this series, we will read:

“The Flea”

More likely to be added! Make your requests known!

***

BOOK NOTE:

Earlier this spring, a beautiful book of prayers and devotionals penned by various classical voices throughout church history released. Cloud of Witnesses: A Treasury of Petitions and Prayers through the Ages by Jonathan W. Arnold and Zachariah M. Carter is just what the title suggests it is. It is also a lovely physical book — a little compact hardcover voume with a ribbon book mark sewn in. (I love a high quality book!) Helpfully, the entries are arranged topically with indexes included also by topic and well as by name. I always find reading the ancient and early modern Christians edifying and instructive. So much of what we wrestle with today has been wrestled with before! I find myself often needing reminders of that. And the language of these writers is so nuanced, rich, and beautiful. Since we are immersed in Donne right now, I thought this book would be an excellent one to note.

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”1

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

Could "our best men" be referring to martyrs for the faith? Donne lived right in the middle of the era of Protestant Catholic conflict in Europe.

This sonnet goes so well with Donne's 'Devotions upon emergent occasions', which were written during the severe illness that preceded his own death. Death is a topic that is seldom addressed in modern churches - despite our declared faith that Christ will destroy the last enemy of death - to our great spiritual detriment, I think. Abusive ministers can forget they will one day be called to account, and congregants are left without counsel and comfort for when they face death.

Karen, this study is personally timely. This past week, I saw three specialists who emphasized that I needed some new symptoms investigated as soon as possible. There was an urgency to their words and actions that startled me. As a healthcare professional myself, I know what my symptoms might mean, but I have been trained to not immediately go for the most dramatic diagnosis. It might still be a less dramatic diagnosis, but their urgency was a sharp reminder of my own mortality.

I love the metaphysical poets, and especially John Donne. I think he wrote this after experiencing the deaths of several people he loved, including his wife. Anyone living in that time would be intimately acquainted with death, which makes his brash confrontation of Death all the more meaningful. Thanks for covering these in our class, Karen!