[Photo of Monmouth Academy in Monmouth, Maine, where I spent most of my middle and high school years. Photo taken in 2016 by Joe Phelan/Kennebec Journal]

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.” – Simone Weil1

This is the first fall I won’t be going to school since I was five years old.

This fact is surreal to me.

I have loved school since the first day. I loved the pencils and the plastic slide top pencil boxes. I loved vocabulary lists and spelling tests. My metal lunch boxes, rubber cement, spiral bound notebooks, and the Trapper Keepers. New school clothes. I lived for the Scholastic Book Club. I loved book reports and research papers. I loved English, French, Latin, and Mrs. Lovejoy. I especially loved Mrs. Lovejoy.2

I was the kid who never missed school unless I was really sick. On those rare occasions, I would watch the school bus drive away from my window without me on it and feel like something was terribly wrong with the world.

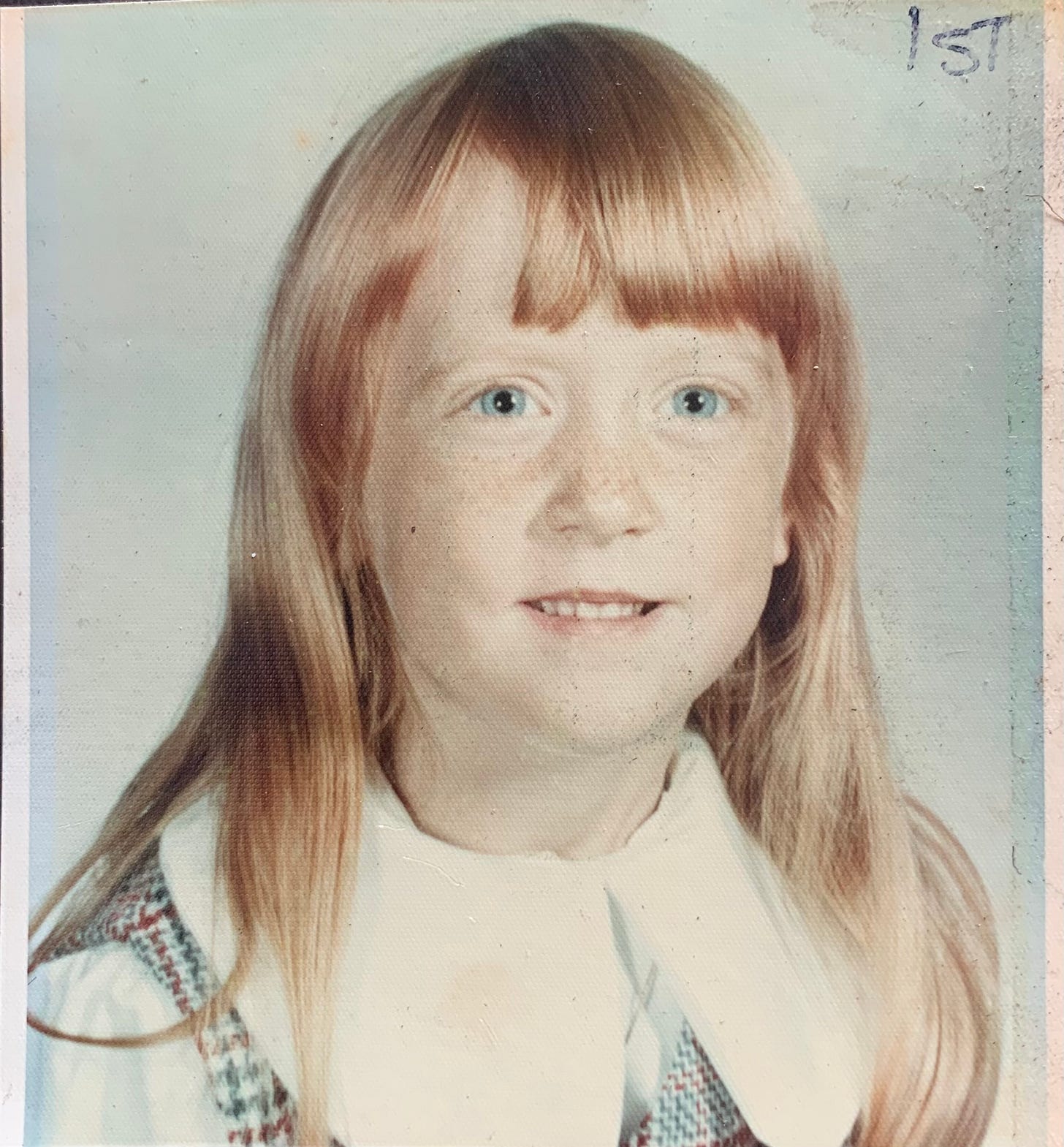

[My first grade picture. Those bangs! That collar! Those freckles.]

I loved school so much that I never wanted to leave.

Not even now.

So as this late August approached, I didn’t know how I’d feel when nearly everyone I know would be heading back to classes … and I wouldn’t be.

I’m not as sad as I thought I’d be. Truth be told, I think I’m so exhausted and numb that the sharpness of the edge has been dulled. Pain and loss have a way of wearing you out.3

Yet.

Many have shared with me that they think God is going to do something new and wonderful in this next chapter. And I believe it. Not only because I have faith (which I do) that this is so. But also because I have a peace that surpasses my understanding.

Not that it’s all sunshine and roses.

The low points are not as low as they have been over the past several months nor are they as frequent. That is a mercy of time, healing, therapy, and love.

A recent low point was when I was setting up this substack account. I was trying to figure out how to make the banner image that comes in the weekly email to subscribers. I could not figure out how to make a simple graphic. An hour later, I was in a downward spiral thinking about how hard I worked all those years ago to get my Ph.D. and how many years I have been teaching literature as a college professor and none of that was being put to use in trying to make a stupid graphic. It felt like all that time, knowledge, and experience had been thrown in the trash heap. (I know that’s not entirely true. But let’s be honest: it’s partially true.)

Anyway, a friend answered my call for help and made the banner. (Thanks, Chad!) Now when you see it in your inbox, you will know the story behind it.

But . . . back to school. To going back and to not going back.

The most difficult back-to-school experience I ever had (well, besides this one of not going back) was five years ago when I was still recovering from being hit by a bus. (If you are new around here and don’t know that story, you can read about it here.)

I was still in a wheelchair during our faculty meetings before the start of classes. But by the time classes began, I had graduated to a walker. Believe me when I tell you that preparing myself to go back to school in that condition was one of the most trying emotional, physical, and mental experiences of my life.

Here are some pictures of that day (two taken by my mom, just as on back-to-school days of years past!)

Seeing these pictures five years later (almost to the day) raises a lot of feelings. Gratitude, of course, for just surviving (and for so much healing). Love for all those who helped me during that time. Pride—in myself for doing the hard thing. And a feeling of fun for that unexpected kinship with my literary hero, Flannery O’Connor.

I don’t know if you can see it or not, but what I also see when I look in the eyes of those pictures of me on that day is pain—pain glazed over by opioids. There was an awful lot of pain. For a long time, I thought it would never go away.

But it mostly has.

I am tearing up just now writing that.

It fills me with gratitude and with hope—about all the other pain that has come. It, too, will go away. Maybe not entirely. Actually, definitely not entirely. (Ask me how I know.)

One of the reasons I started this newsletter was to find a way to help fill the hole in my life that has come with not being in the classroom. And it recently occurred to me that I could—just for fun, as an experiment (only you, dear readers, will determine how it goes!)—journey here through some of the literary works I would be teaching if I were teaching my usual British Literature survey.

What do you think?

I’d start, as usual, with the Old English period (Beowulf! The Dream of the Rood!), then Middle English (Chaucer!), get to Shakespeare, and so on. This could take all semester. Or all year!

You, my readers, aren’t college sophomores, of course. (Or maybe one or two of you are?) There will not be an exam!

I’d write a bit about these works, their background and significance, but also (as I do in the classroom) make real life connections. And I will always reserve the right to take a week off and do something else as the spirit moves.

So next week, I will begin and then see how it goes.

The first work I teach in my British Literature survey is Beowulf. You can find various versions of it online, but here’s one, translated by the Irish poet Seamus Heaney. I like this translation, and I also like the way it is formatted on the page, not only with the Old English line, but with each line large and distinct. For the best way to read good literature is slowly. In fact, I think it’s better to read a little well than to read a lot hurriedly.

Speaking of Irish poets, here’s a poem by another Irish writer, William Butler Yeats. It’s called “Among School Children” (1928):

I I walk through the long schoolroom questioning; A kind old nun in a white hood replies; The children learn to cipher and to sing, To study reading-books and history, To cut and sew, be neat in everything In the best modern way—the children's eyes In momentary wonder stare upon A sixty-year-old smiling public man. II I dream of a Ledaean body, bent Above a sinking fire, a tale that she Told of a harsh reproof, or trivial event That changed some childish day to tragedy— Told, and it seemed that our two natures blent Into a sphere from youthful sympathy, Or else, to alter Plato's parable, Into the yolk and white of the one shell. III And thinking of that fit of grief or rage I look upon one child or t'other there And wonder if she stood so at that age— For even daughters of the swan can share Something of every paddler's heritage— And had that colour upon cheek or hair, And thereupon my heart is driven wild: She stands before me as a living child. IV Her present image floats into the mind— Did Quattrocento finger fashion it Hollow of cheek as though it drank the wind And took a mess of shadows for its meat? And I though never of Ledaean kind Had pretty plumage once—enough of that, Better to smile on all that smile, and show There is a comfortable kind of old scarecrow. V What youthful mother, a shape upon her lap Honey of generation had betrayed, And that must sleep, shriek, struggle to escape As recollection or the drug decide, Would think her son, did she but see that shape With sixty or more winters on its head, A compensation for the pang of his birth, Or the uncertainty of his setting forth? VI Plato thought nature but a spume that plays Upon a ghostly paradigm of things; Solider Aristotle played the taws Upon the bottom of a king of kings; World-famous golden-thighed Pythagoras Fingered upon a fiddle-stick or strings What a star sang and careless Muses heard: Old clothes upon old sticks to scare a bird. VII Both nuns and mothers worship images, But those the candles light are not as those That animate a mother's reveries, But keep a marble or a bronze repose. And yet they too break hearts—O Presences That passion, piety or affection knows, And that all heavenly glory symbolise— O self-born mockers of man's enterprise; VIII Labour is blossoming or dancing where The body is not bruised to pleasure soul, Nor beauty born out of its own despair, Nor blear-eyed wisdom out of midnight oil. O chestnut tree, great rooted blossomer, Are you the leaf, the blossom or the bole? O body swayed to music, O brightening glance, How can we know the dancer from the dance?

Yeats’s poetry is deeply philosophical and dense, and this one alone, one of his most famous, has volumes of criticism written about it. I include it here merely to reflect briefly on how the mood and setting of the poem illuminate my own time of life and its musings.

This somewhat autobiographical poem marks a time when Yeats, at age 60, visited a convent school. He does so as a “public man” whose public role means nothing to these students with their neat modern ways. (Nor should it.) His reveries cause him to reflect on the contrasts between youth and age, expectations and reality. He thinks about the woman he loves being a child like one of these before him now. He considers that Aristotle, who taught Alexander the Great, disciplined the future king. He wonders whether a mother would consider her birth labors worthwhile were she to see into the future at her aged child grown feeble and old (like the poet). Mothers, like nuns and lovers, tend to love (and even worship) in ideals, like those about which Plato philosophized. But in the end, the poem concludes, body and soul are one. The essence of a tree is in all it is and does, just as a dancer becomes through the dance. Like a poet and the poem. And the teacher and the taught.

In next week’s post, I have some things I want to say about higher education, languages, and literature more generally. That will give you a little more time, should you want to read (or re-read) Beowulf a little on your own before I post about it in two weeks.

Again, I really don’t know how this will go, dear readers. Let’s just see. Together.

Thank you for being here. You don’t know how much it means to me.

(Note: if you’re new here, first, welcome! Second, I invite you to read my very first newsletter. It not only introduces me but also introduces my current situation which produced The Priory. Weekly newsletters are free, but a paid subscription helps support all the other work I do—and lets you join this community in the comments.)

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

You can read more about Mrs. Lovejoy in my chapter on Great Expectations in Booked: Literature in the Soul of Me (T. S. Poetry Press, 2012).

Ah. I first drafted this newsletter about a week ago. Now, on the eve of its publication, when all (it seems) of my friends and colleagues are back in the classroom and posting about it, it’s a little harder. But that was to be expected, I suppose.

Karen, you are awesome! I am so sorry about your having to leave your teaching position. I grieve for the students who will miss your excellent teaching. But I also appreciate your faith that God is doing a new thing. Thank you for sharing on this platform. You are loved with an Everlasting love, and underneath are the Everlasting Arms.

So grateful you are here! I have always wished I could be one of your students, but thoroughly enjoyed and gleaned much from you online for many years! As a former teacher (before business owner) I relate to the joy of returning to school and how strange it was when that shifted. I pray God fills your heart and future with satisfying work, ministry and much peace as you continue to heal! Keep writing my friend! The world needs more KSP! ❤️