The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus: Week 2

A Sound Magician is (Not) a Mighty God

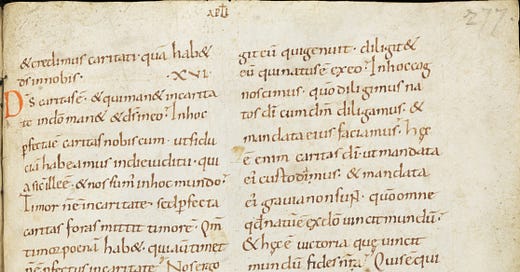

[8th-century Vulgate manuscript (Codex Sangallensis 63) with the Comma Johanneum at the bottom margin; public domain]

Last week we left off with Dr. Faustus sitting in his study. Now we shall see in Scene 1 what he is doing there.

Faustus begins a long monologue. He is thinking out loud, making us privy to his reflections upon having just completed his doctorate and contemplating what is next for him (as all graduates do!).

For a bit of context, it helps to know that in the medieval university, doctoral students were not as specialized as they are today. A person earning the title of “Doctor” studied all the major disciplines, much the way a liberal arts undergraduate does today. A man earning the “Doctor of Philosophy” degree had learned from all the fields of knowledge (“philosophy” means “love of wisdom,” after all). Thus, a “Renaissance man,” like our own Faustus, was well-rounded rather than specialized in learning. Today, in contrast, with all the knowledge that has been added to every discipline in the ensuing centuries, those with the title “Doctor” have studied in a much narrower area of expertise. Specifically, those with a Ph.D. are expected to have contributed some small bit of original research to a very thin slice (relatively) of specialized study.

But Faustus, having studied all the fields of his day and having excelled quickly (as the Chorus relays in the Prologue) is feeling a little full of himself. one by one, he considers each of the areas he has studied. And one by one, he considers the limits of these areas of knowledge.

First he contemplates logic (“analytics”), the aim of which, Faustus says, is to argue (or dispute) well. That purpose does not seem satisfying to Faustus. (Nor should it.)

And here is where we ought to begin to be alert to Faustus as an unreliable character.

For the purpose of logic is not to argue well, is it? The purpose of logic is the discovery of truth. Arguing well is the means toward that larger purpose. But Faustus either ignores or denies this truth.

So he moves on to consider the next field he has studied: medicine. The end or purpose of medicine, Faustus observes, is bodily health. So far, so good. That seems correct. Indeed, Faustus has, as a physician, aided whole cities in escaping the plague and brought healing to a thousand different illnesses—a measure of great success in the field by any standard. And yet it seems pointless to Faustus. Why? Because despite being able to prevent and heal sickness, he cannot make men live eternally or raise them from the dead. (Are you hearing this? Faustus is not satisfied with his accomplishments in this field basically because he is not Jesus. What a guy!)

So he goes on to weigh his studies in the field of law. Law bores him. It is “petty” and “paltry,” he says, after quoting one particularly inane Roman code. Law is the work of “a mercenary drudge” (LOL! I think of a lot of lawyers I know today who might agree). Lawyering is work too “servile and illiberal” for Faustus.

“When all is done,” Faustus says, of all the things he has studied, “divinity is best.” Now, we might think, at last Faustus will be satisfied. He is right that the study of God is the most important study of all. We might feel a little relieved for Faustus at this point. But we ought not speak too soon …

To consider divinity, Faustus quotes from Roman 6:23 and 1 John 1:8 which convey the biblical truths that we all have sinned and that the penalty for sin is death. “That’s hard,” he says. And indeed it is. (Faustus is certainly using very well the logic he has studied!) And yet, Faustus fails to complete his citation from the verse from Romans 6, which goes on to say, “but the gift of God is eternal life.” Failing to consider that life-giving part of the text, Faustus bids adieu to the field of divinity.

We have been expressly told that Faustus excelled as a student. Surely, he must know how to read the Bible in context. He must know not to cite a partial verse, right? Surely, then, he must be choosing here to omit the most important part of the quotation in order to justify his dismissal of the study of divinity. (I have seen some theologians do very similar things on Twitter!)

Furthermore, I recall reading long ago that the Latin Vulgate, Jerome’s translation, the one from which Faustus quotes, would not have been considered the most authoritative translation even at this time. If this is the case, then Faustus is really not being the good student he is perfectly capable of being.

Such is the power humans—even the smartest and most educated ones—have to rationalize the wrong we are about to do.

After all, Faustus is about to turn to the forbidden field of necromancy, the deadliest wrong he could do. All the talk before this point in Scene 1 has simply been his justification for doing so.

Thus begins a moving and powerful passage from this opening monologue which you can read (or listen to) here in a moment.

First, let me invite you to pay attention to what Faustus thinks he will be able to do upon grabbing hold of these dark powers. At the end of the play, we will want to compare what actually happens to what Faustus expects will happen. Let us note, too, that the remainder of this scene presents the first of many warnings Faustus receives (and ignores) throughout the play to turn away from these dark arts. Of course, he also has friends eager to help him along what will prove to be the way of destruction.

But death and destruction are far from Faustus’ mind as he imagines (wrongly) what will be in store for him by obtaining forbidden knowledge. Here is what he envisions:

O, what a world of profit and delight,

Of power, of honour, of omnipotence,

Is promis’d to the studious artisan!

All things that move between the quiet poles

Shall be at my command: emperors and kings

Are but obeyed in their several provinces,

Nor can they raise the wind, or rend the clouds;

But his dominion that exceeds in this,

Stretcheth as far as doth the mind of man;

A sound magician is a mighty god:

Here, Faustus, try thy brains to gain a deity.

At this point in my commentary, I’ve loaded the deck, so to speak, against the character of Faustus. To be sure, I don’t think we’re supposed to be all that admiring of the guy who sells his soul to the devil. Therefore, I want to make it a point to encourage you as you read along to look for the ways in which Marlowe complicates the character of Faustus. Faustus wouldn’t be a character who has so captured the cultural imagination for hundreds of years if he were totally flat and 100% villainous. And this play wouldn’t be the masterpiece it is if it didn’t tap into something complex, interesting, and insightful about human nature and the human condition.

So keep these questions in mind: What is it about Dr. Faustus that appeals even as it warns? What is it about Faustus that illuminates the darkness in our own desires and our own souls? What is it about his Renaissance man that speaks to us all still today?

Next week, Scene 2.

***

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.” – Simone Weil1

***

If you are near Houston or Grand Rapids later this week, you can find me here:

Houston, TX: Thurs. April 11, Memorial Drive Presbyterian Church, 7 p.m.

Grand Rapids, MI: Fri-Sat. April 12-13, Calvin University, Festival of Faith and Writing (Full schedule here: https://ccfw.calvin.edu/festival-2024/plan-your-visit/festival-schedule/)

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

Thank you for your excellent summary and commentary on Marlowe's "Dr. Faustus." I feel I missed a great deal of magnificent English literature during my many years in higher education. Never too late to be taught by one of the best instructors!

Hi Karen,

I'm "glutted" with other reading and writing projects so I am reading your wonderful summaries and analyses and hoping to catch up on reading the play.

I'm thinking of Paradise Lost and what influence this play may have had on Milton. If Milton's object is to explain the ways of God to man, Faustus seems to be explaining the ways of men to men.