The Pilgrim's Progress: Week 5

From the Depths of Despair to the Heights of the Delectable Mountains and Beyond

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.” – Simone Weil1

I confess that when I made the timeline for our reading of The Pilgrim’s Progress, I was going roughly by page numbers in an attempt to cover a reasonable amount of pages each week. That was not the best way to go about it. Nor, I suppose, was covering so much in so few installments! But, alas, there are so many books, and so little time.

This week I had an exceedingly difficult time trying to figure out what to cover and what to not cover since so very much is going on in this week’s segment … So here’s what I decided on. I’m going to try to cover it all (or most of it). This week, I will sacrifice depth for breadth in attempting to say a little something about all the major places, characters and events described in this week’s pages and the larger truths they reveal.

Here goes:

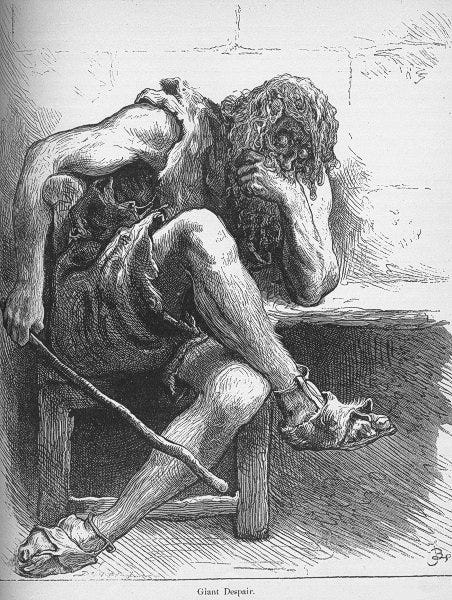

Despair (both the character and the mental state) is a giant. He is exceedingly cruel. (His modern name might be depression.) He lives in a castle called Doubting. (Note that doubt follows despair. I think Bunyan is insightful here.) Despair seizes Christian and Hopeful after they have trespassed onto his grounds after taking a by-path rather than staying on the more difficult road. (Despair is not always or even often the direct result of our own choices. But surely sometimes it is, and that is what Bunyan depicts here.) Despair puts the two in a dungeon that is dark, “nasty and stinking.”

The wife of Despair, Diffidence—which means lack of faith or confidence—advises Despair to “beat them without any mercy.” (Don’t despair and lack of confidence always go together?) Not only does Despair do what Diffidence bids, but he even encourages Christian and Hopeful to so fully embrace him (Despair) that they will take their own lives.

Hopeful encourages Christian to be patient and persevere. (We all need a Hopeful in our lives!) Despair doubles down and shows them the skulls and bones of those whose lives he has taken before. (Despair has indeed taken many lives.) All hope seems lost. But when the two pray, Christian remembers that he actually has a key that can open any lock in Doubting Castle. The key is Promise. I think it is the promise of their salvation, but also all of God’s promises (and not in a prosperity gospel kind of way). It’s important to note that Bunyan does not have Christian and Hopeful pray their despair, or depression, away. Rather prayer brings them the remembrance of their salvation, remembrance of God’s promises for the future, even when they don’t know what that future holds. I think of the promise of Romans 8:28, that God will work all things together for good for those who love him—that’s a promise, but we don’t know what form the fulfillment of that promise will take. (I see this over and over in my own life—God working things together for good, good I never could have quite imagined.)

Remembering plays an important role, not only in this episode, but throughout the narrative as Christian constantly needs to recount and remember all he has been through and all the ways he has persevered and all the ways God has been faithful. Remembering the past propels him forward.

It's tempting at this plot point to complain that it’s not at all “realistic” on the literal level of the story to go through so much torture and pain and starvation and imprisonment and then, so much later, to remember you had a key to escape in your pocket (or bosom) all along! But on the allegorical level, doesn’t this ring really true? Isn’t it so easy to “forget” (or ignore or downplay or minimize) the promises of the Lord in the midst of our real life anxieties and problems? I know it’s easy for me.

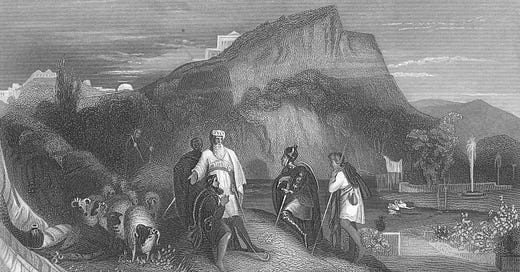

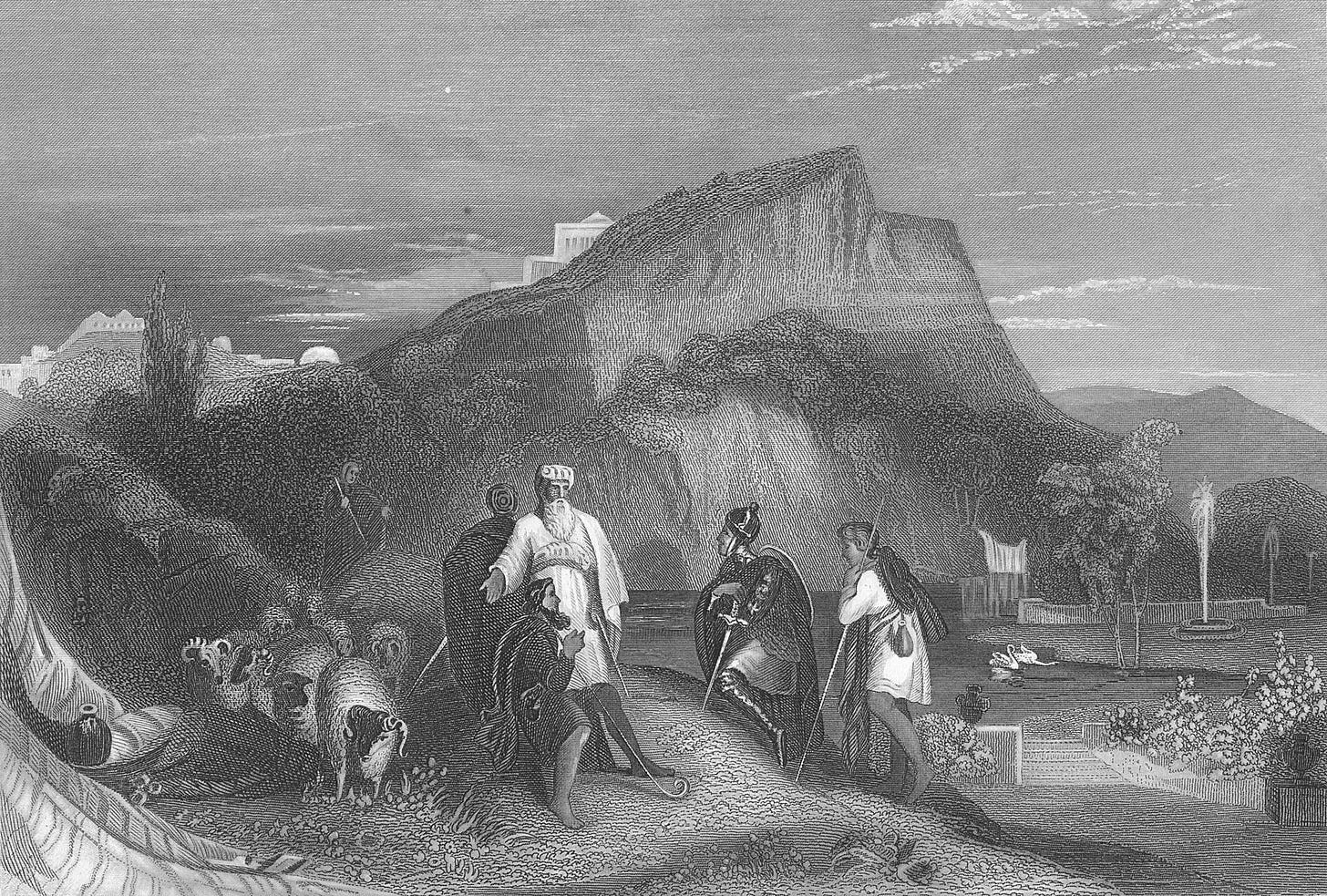

From the depths of despair, Christian and Hopeful ascend to the Delectable Mountains. (So often the Christian journey is a spiritual roller coaster, isn’t it? Now whether it should be or need be a roller coaster is a question for another day.) These refreshing, peaceful mountains belong to the Lord, it turns out (“and the sheep also are his, and he laid down his life for them”), the place not far from the Celestial City. Christian and Hopeful are back on track—for now.

They are welcomed by shepherds whose names are Knowledge, Experience, Watchful, and Sincere. These are good shepherds. (They are not the wicked pastors who are being exposed day after day, week after week, for their lying and manipulation and slanders. Have you been on social media lately? Wow. If so, you know what I’m talking about.) These shepherds guide and teach. (I take so much comfort in being reminded that this is what true shepherds do. Bunyan knew and he reminds us.) They warn the pilgrims about the mount of Caution and the by-way to hell (which terrorizes the pilgrims upon looking in).

But it’s not all about warning, denouncing, decrying, the way so many “pastors” do today. The pilgrims “desire to go forwards,” and the shepherds desire to do so with them. So the shepherds journey with Christian and Hopeful up the “High Hill called Clear” from where they will be able to see the gates of the Celestial City through a perspective glass (or telescope). But Christian and Hopeful are still so upset by the scene in the hill where they got a glimpse of hell that their hands shake as they hold the glass. Even so, they faintly see “something like the Gate, and also some of the Glory of the place.” Their eyes are back on the prize. “Then they went away and sang.”

As Christian and Hopeful journey nearer to the Celestial City, they meet more pilgrims on their way, too. Upon leaving the Delectable Mountains, they next encounter Ignorance, who hails from the Country of Conceit. Now we have studied the literary conceit here at The Priory. It is, basically, an elaborate metaphor. And most of us have a sense of what it means to be conceited—to be puffed up, full of oneself. I hope you can see how the two usages are connected. Both the literary conceit and the conceited person are “full” of themselves. And so Ignorance, from Conceit, has a works-based approach to salvation. He did not come through the Wicket Gate (Christ) but rather relies on his knowledge (ironically, Ignorance has a lot of it, but it is what we might call “head knowledge”). Ignorance is “wise in his own conceit.”

Next, they encounter Turn-away, an apostate who has turned away from the faith. Turn-away has been bound and is being carried by seven Devils back to hell, the door of which Christian and Hopeful had peered through earlier. Ignorance continues on his merry way, but Turn-away ultimately loses his agency and is given up to the demons. (Doesn’t this really ring true?)

Christian then tells Hopeful the story of Little-faith, a poignant, heart-rending story. Little-faith has faith, but it is weak. When he encounters those who would rob him of his faith—Faint-heart, Mistrust, and Guilt (aren’t they always the ones trying to steal our faith?)—they get away with nearly everything but Little-faith’s jewel—the salvation he has in Christ which cannot be taken away from him.

Little-faith is the kind of believer we might call today a “baby Christian.” Such a one has the saving knowledge Ignorance lacks, but has no maturity or strength. Little-faith comes from the town of Sincere. (Ugh! It rings so true.) I can’t help but think of the many, many self-identified Christians in polls and surveys who indicate how little of orthodox Christian teaching they believe or how much of their trust they put in government and politicians to correct our nation’s wayward stances. Based on guilt, mistrust, and fear, they make decisions that reveal lack of true discipleship. But they are so sincere.

In contrast to those of little faith (Jesus had much to say about these) we have those of mature faith, strong in the Lord, like Great-Grace, the King’s champion from whom the villainous robbers flee in an instant. In contrasting Little-faith and Great-Grace, Christian explains to Hopeful, “All the King’s subjects are not his champions, nor can they, when tried, do such feats of war as he.”

This is a hard word for me from Bunyan. He may be talking about the weaker brother versus the stronger brother. I have learned over my years of teaching and working with Christians of various degrees of maturity to be forbearing with the weaker siblings. But I admit that in current days my patience is wearing thin. I also confess that I am increasingly inclined to believe that those I once thought were like Little-faith are in fact more like Ignorance. Or Talkative. Or Formalist. Or Hypocrisy. Or Flatterer.

Flatterer encounters Christian and Hopeful on their way and leads them astray, despite the warnings they had been given by the wise shepherds, and that way leads them into a net. There “they were so entangled that they knew not what to do.”

They are rescued by a Shining One who carries a small whip (a symbol of discipline) and is one of a group called the Shining Ones. Christian encountered three of these Shining Ones earlier in his journey at the foot of the cross when one blessed him with peace, another pronounced his forgiveness, and a third gave him the roll with the seal upon it that is the assurance of his salvation.

By now you have likely noticed how Bunyan uses parallels, repetitions, along with binary pairs and oppositions as foils that further illuminate each character, place, and event. At the same time, he brings so much nuance and complexity to the symbols in his allegory. Some characters are clearly good or evil, but many are shades and variations in between. Isn’t this just like real life? Just like the real pilgrimages we are all journeying on?

I am newly challenged each time I read this work.

Next week, we wrap up Part 1 of The Pilgrim’s Progress!

We will have a guest post from Jack Heller, then a break, and then move on to Part 2 of The Pilgrim’s Progress.

I want to try a different pace and see how it goes. Let’s break the reading up into fewer chunks but go two weeks in between. I don’t know if this will work well. But let’s give it a whirl.

Here is the schedule for Part 2 (I will confirm when we will start, but these are the sections):

From the beginning to Of Grim the Giant and of his backing the Lions

From Of Grim the Giant and of his backing the Lions to Mathew and Mercie are Married

From Mathew and Mercie are Married to One Valiant-for-truth beset with Thieves

One Valiant-for-truth beset with Thieves to the end

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

Little-Faith keeps his scroll and his jewels. He isn't a great Christian, but he is a Christian. He reminds me of an elderly acquaintance whom my parents drove to church, who was always morose, always took the gloomier view of things, but still came to church, still believed, and did no one any harm.

Unlike the Valley of the Shadow of Death, which describes OCD symptoms so well, Doubting Castle gives a clear picture of depression. I do think Bunyan was incorrect to think Christian ends up captured by Despair because he took a by-path, because I know Despair menaces Christians who are still on the path. Once again, I know a believer who very nearly, more than once, took the route Despair tries to make Christian and Hopeful take. I disagree with Bunyan that suicide bars one from the kingdom, as I think Bunyan fails to account for the distortion of the mind brought on by mental illness - the Bible does take into account when someone does not know what they are doing. I often recognize Bunyan struggling for the conclusions that I have reached in my own experience - he is nearly there, but the prejudices of his own era are blocking him from fully grasping them.

I'm just making my way through the comments, so I am hoping I'm not just repeating something already said. Yes, I do think there are some problems with Bunyan, including with some of what he shows as characteristic of the Christian life. I'm not a scholar of melancholy, but clearly, Bunyan represents some of the ideas of his time. I would recommend, sort of, reading his autobiographical work Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners. (Sort of, because it is a downer.) Bunyan struggled with the despair/depression he wrote about. He truly takes himself as the chief of sinners.

I intend to say a few things about the Flatterer in the piece I'm writing, but I can note a few things here: Someone noted that he doesn't actually say anything flattering. Other characters, including Wanton, are said to have said flattering things. According to the edition of PP on Project Gutenberg (which I don't entirely trust as an authoritative text), even Apollyon flatters.

It's not the Flatterer's words but his clothing that suggests that he's an "angel of light." It's when he loses his clothing that Christian and Hope see the Flatterer for what he is . . . a black man. The conflation of blackness with sin is central to the history of racism, and unfortunately, Bunyan perpetuates the conflation.