The Pilgrim's Progress Part 2: Week 1

"Mehinks it makes my heart bleed, to think that He should bleed for me."

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.” – Simone Weil1

Part 2 of The Pilgrim’s Progress was published in 1684, after numerous editions of Part 1 had been published and gained tremendous popularity.

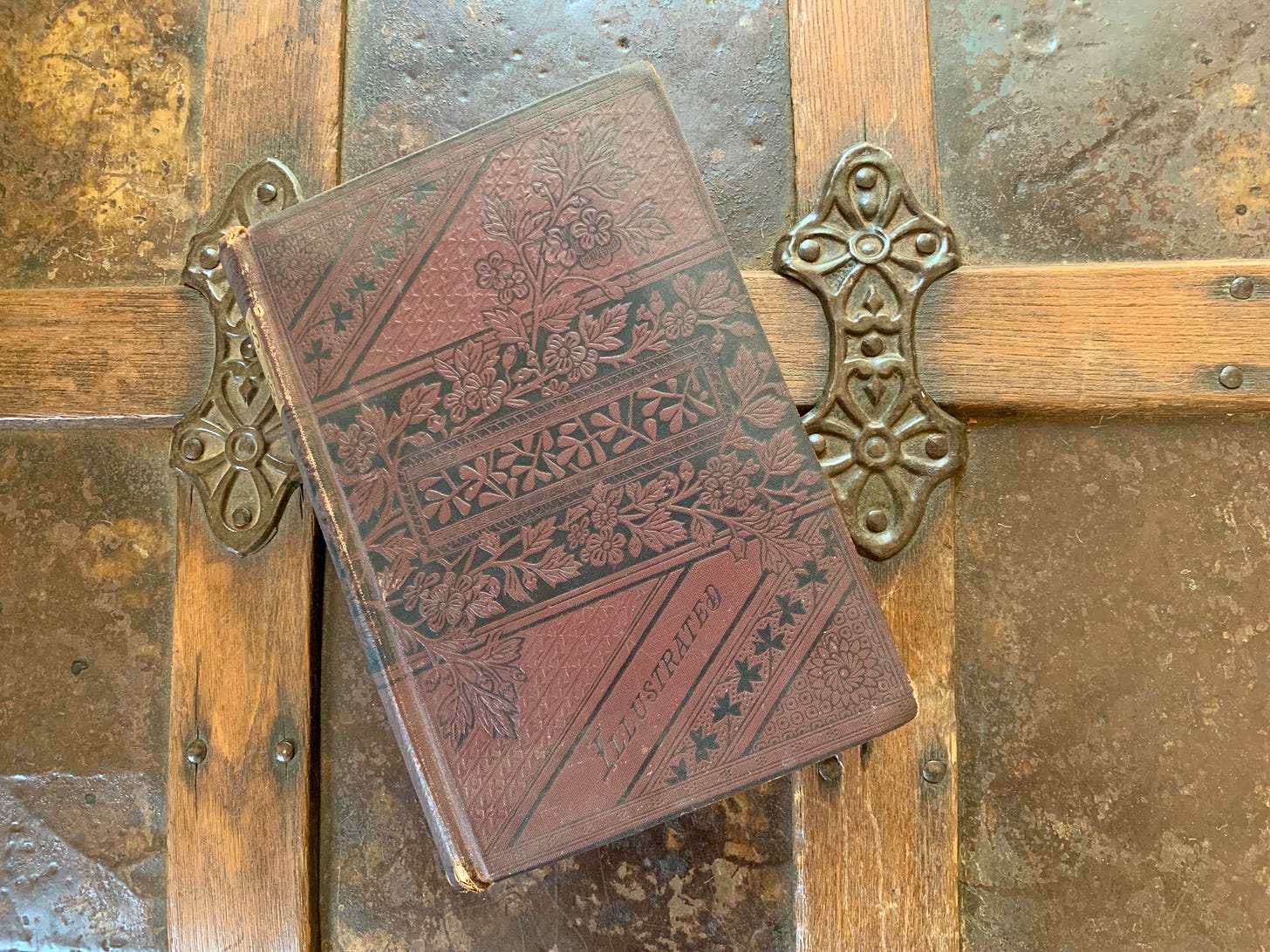

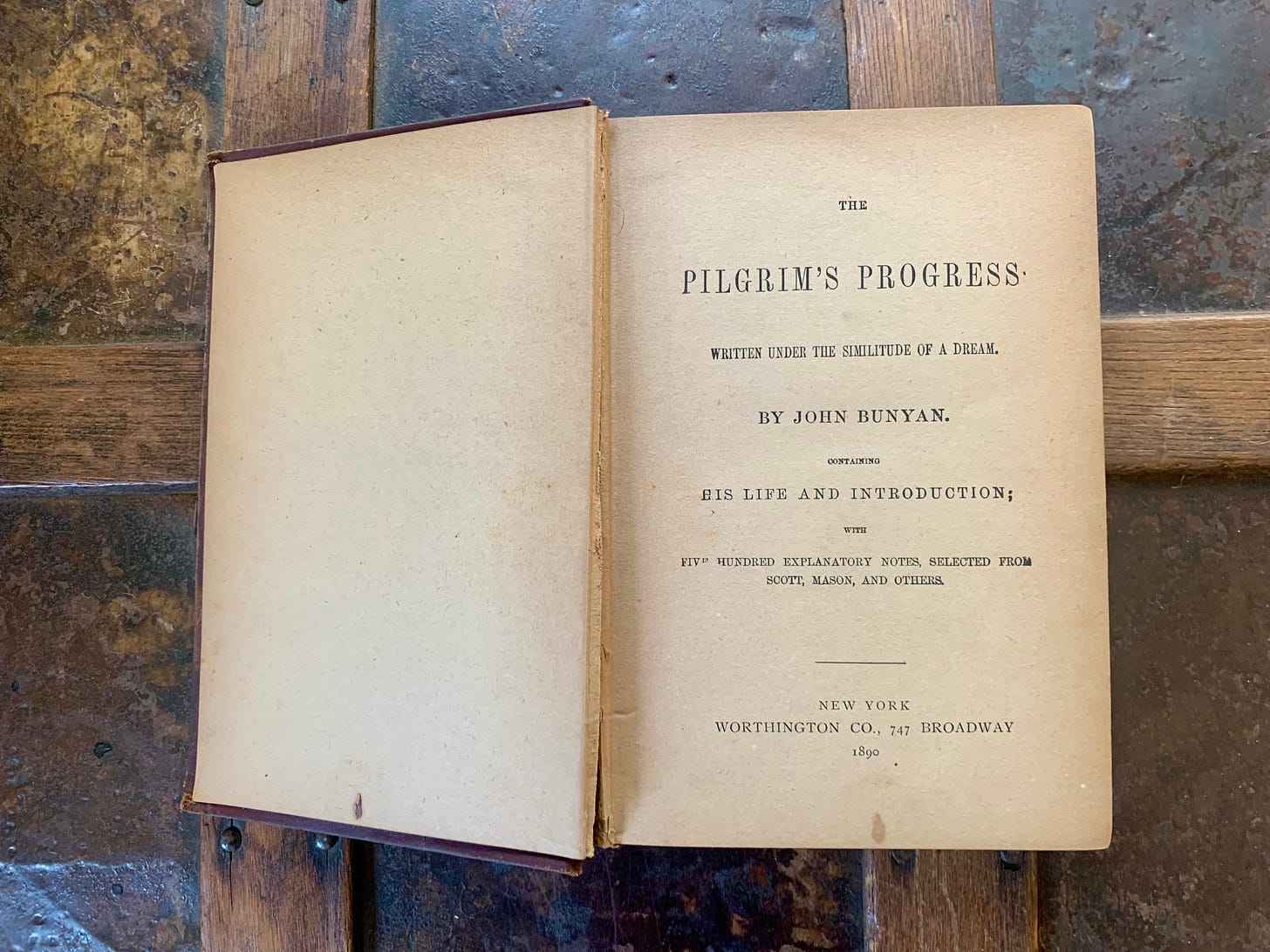

Part 1 is read, adapted, and known far more than Part 2. Some folks are even surprised to learn that there is a Part 2—the journey of Christian’s wife, Christiana, along with their four sons, to the Celestial City. Most good editions of the work will contain both parts. But there is much more profit to be made from reproducing or adapting the better-known half of the work, and so (it seems), many do. I’d be very curious to hear from you, readers, about your own familiarity with Part 2 and whether or not it is included in the editions you have read. The oldest copy of The Pilgrim’s Progress I own (pictured above and below) was published in 1890 and does include both parts, although, sadly, it omits Bunyan’s notes in the margins.

Considering the similarities and differences between Part 1 and Part 2 is an obvious and inevitable approach to take in reading them. Of course, it’s important to consider the journey undertaken by Christiana and her family and friends in its own right, but Part 2 is, in fact, a sequel, and is understood best as that. On the other hand, because there are so many parallels and contrasts between the two, it’s helpful to consider the ways in which Bunyan “amends” or balances out the picture of the Christian journey given in his first allegorical telling.

One striking (and, for some, unforgivable) aspect of Part 1 is that Christian abandons his family in order to journey to the Celestial City. This is where it is helpful to remember that the work is an allegory more than a work of realism. After all, Jesus says in Luke 12:51-53 that he came to bring division and that that division would include dividing of families. Still, on the level of the story, it’s hard to grasp. So it comes as some relief that Bunyan as author chose later to bring the rest of Christian’s family along. I like to think of Bunyan being mortified upon realizing after writing his masterpiece that he had Christian leave his poor wife and kids behind and figuring out that he could rescue them by writing a sequel.

Clearly, Part 2 emphasizes family (given that Christiana is accompanied by her and Christian’s four sons) and community more than the heroic individual. I like that Part 2 brings balance to this very real tension that our salvation is an event that is individual and personal, but also one that takes place (or not) under the influence of our communities, including covenantal communities like families and churches. On the other hand, we have to wrestle with the fact that it is the man Christian whose journey is portrayed as one undertaken (more) alone, that Christian is, from the start, portrayed as an individual (almost a modern one). Christiana, in contrast, the woman, begins and ends her journey in company, with family. She is not seen as an autonomous individual with as much agency as her husband. This is, of course, of the times (Bunyan’s times, perhaps even our own). But I will note as a gesture toward future installments of our chronological literature survey that later writers (early novelists of the next century, to be more specific) will often offer female characters as the most apt site for the expression of the modern, pioneering individual. But Bunyan’s gender dynamics are more complicated than the worst stereotypes would suggest.

In Part 1, “Christian discovers that pilgrims like himself are actually able to help one another; indeed (though never taking their eyes off their personal salvation), they absolutely need one another,” writes W. R. Owens in the introduction to the Oxford World Classics edition of The Pilgrim’s Progress. But in Part 2, Owens says, the place of “human companionship and mutual support” becomes “the dominant theme.”2

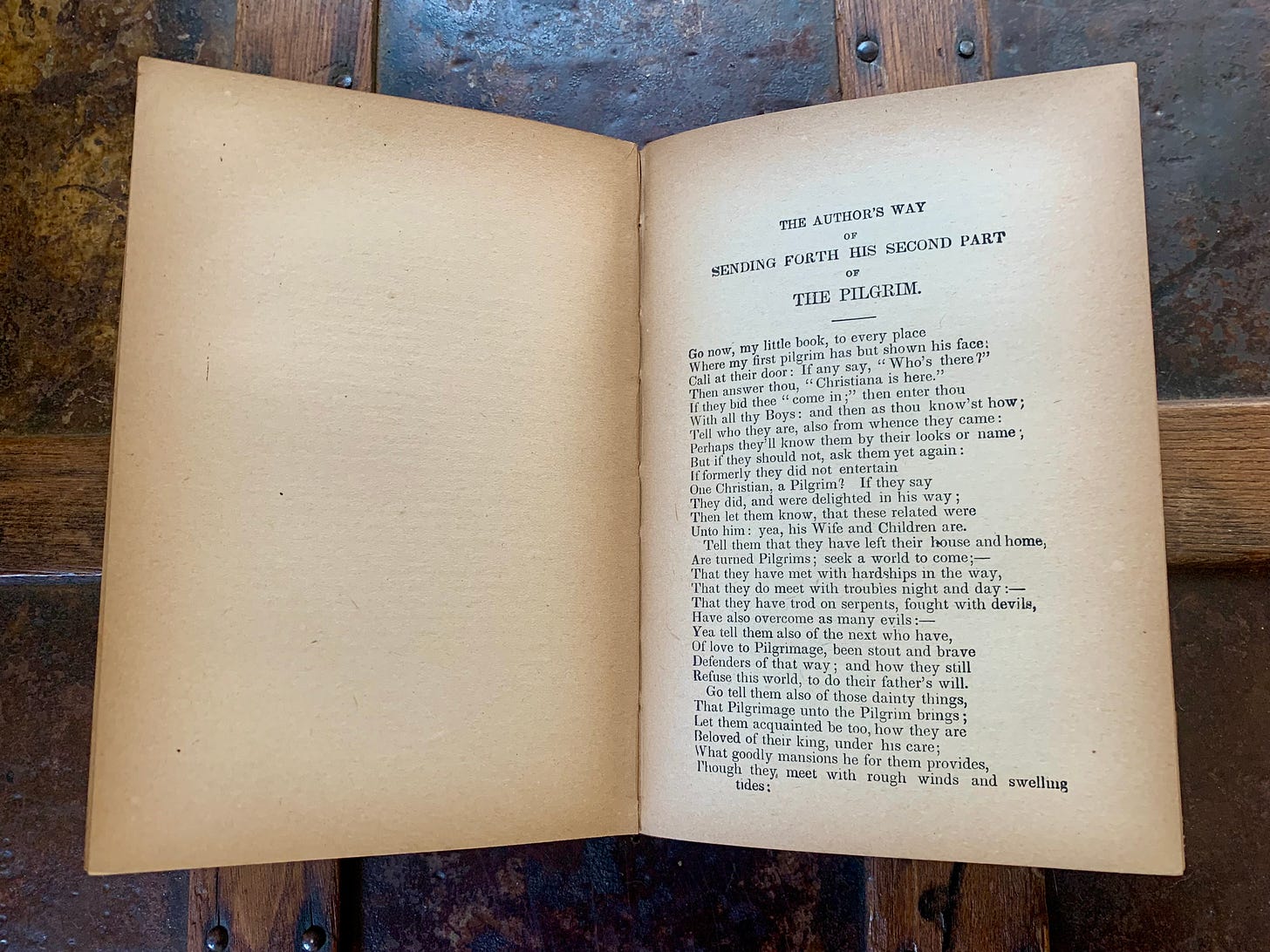

In his opening apology for Part 2 (recall that a similar one prefaced Part 1), Bunyan announces this second book, calling it by the name of Christiana, then having a dialogue with his work. This brings to mind another Puritan and another work: “The Author to her Book” by the New England Puritan poet Anne Bradstreet (1612-1672). In the poem, Bradstreet offers an apology for her book by addressing her book as a person (more specifically, her child). Bradstreet’s poem was published (posthumously) in 1678 and very well could have been read by Bunyan, given the wide and immediate readership Bradstreet gained in both America and England. In his preface to Part 2, Bunyan similarly personifies his work and engages it in conversation, all as a frame for offering a defense of this work as he did for the previous one, this time with the more formal structure of “object[ion]” followed by “answer.” Here, as before, Bunyan defends his use of allegory (in answering the third objection) in addition to defending the authority of the book, the popularity of the first part, and the realism of the story (against the objection that it is a mere “Romance”).

In a bit of an odd twist, the narrative of Part 2 begins with the Dreamer (as before) but employs Mr. Sagacity to bring the Dreamer up to speed on the first part of Christiana’s journey. Once she reaches the Wicket Gate, the Dreamer dreams the rest of her travels.

One sharp contrast between Christian’s journey and that of his wife is that the latter has a constant companion with her, Mercie (along with her sons). As a character and in elements of the plot, Mercie provides a good example of the greater realism that characterizes Part 2 in comparison to Part 1. For example, working class wives would often have hired help around the house, someone who came from a more impoverished household. Christiana would need such help, but more importantly, Mercie provides companionship. Another point of realism is that women would have avoided traveling alone—a phenomenon borne out when the two women are, in fact, accosted by “two ill-favored ones” near the devil’s garden who attempt (rather shockingly, perhaps, to modern day readers) to rape the two women, who cry out and successfully fight them off.

This offers another example of a contrast between Christiana’s journey and that of her husband. The second journey is just as allegorical as the first, but (as I mentioned above) also characterized by more realism (bringing it slightly closer to the soon-to-emerge novel form). While the near sexual assault is presented as a spiritual temptation, it is also clearly a physical and realistic one.3 So, too, is the barking dog that threatens them near the Wicket-Gate. These dangers are just as grave as the Giant and Apollyon met by Christian but are more of this real world than the world of fantasy and romance. This difference has gender implications, as women are traditionally associated with the earthy and mundane, men with the lofty and heroic. (But there is plenty of the fantastical and heroic to come on this journey as well.)

But Bunyan offers many parallels in the two journeys, too. Where Christian met up with Timorous, Christiana meets Mrs. Timorous. Christiana, like Christian, encounters a number of characters with apt names identifying undesirable traits: the blind and foolish Mrs. Bats-eyes, the callous Mrs. Inconsiderate, and that party animal, Mrs. Light-mind, among others.

Christiana, like her husband, comes to the Interpreter’s house and is shown a number of little allegories. Christiana seems in her conversation with Interpreter to be a bit more quick-witted than her husband, usually grasping more easily the significance and symbolism of these scenes. My favorite is the muck-raker—a term that later came to mean a newspaper journalist always looking for scandal.

Here we meet Great-heart, one of Bunyan’s most famous and beloved characters. His name says it all. Well, most of it, but not all. Great-heart is a servant of Interpreter. (Remember that Mercie, too, is a servant.4) Interpreter sends Great-heart along to accompany the women and children upon their departure from House Beautiful, armed to protect them with sword, helmet, and shield.

Great-heart is commonly understood to be drawn by Bunyan from himself—and from any gentle, protective, loving pastor or shepherd. For this is exactly what Great-heart proves to be. He not only protects the travelers from physical dangers, but he teaches them along the way, reminding Christiana and Mercie how their Pardon was obtained and how their Righteousness remains.

When Christiana says of Jesus, “Methinks it makes my heart bleed, to think that He should bleed for me,” Great-heart reminds her it is a gift to be affected with Christ and not one to presume upon. Not everyone is granted such warmth of love, he tells Christiana:

… this is not given to every one, nor to every one that did see your Jesus bleed. There were that stood by, and that saw the blood run from His heart to the ground, and yet were so far off this, that instead of lamenting, they laughed at Him, and instead of becoming His disciples, did harden their hearts against him. So that all that you have, my daughters, you have by a peculiar feeling made by a thinking upon what I have spoken to you. This you have, therefore, by a special grace.

An affection for the Lord Jesus is indeed a special grace.

***

Here is the schedule for Part 2 (we may skip a week between each one to go at a slower pace—just keep reading!)

Current week: From the beginning to Of Grim the Giant and of his backing the Lions

Next: From Of Grim the Giant and of his backing the Lions to Mathew and Mercie are Married

Then: From Mathew and Mercie are Married to One Valiant-for-truth beset with Thieves

Final: One Valiant-for-truth beset with Thieves to the end

***

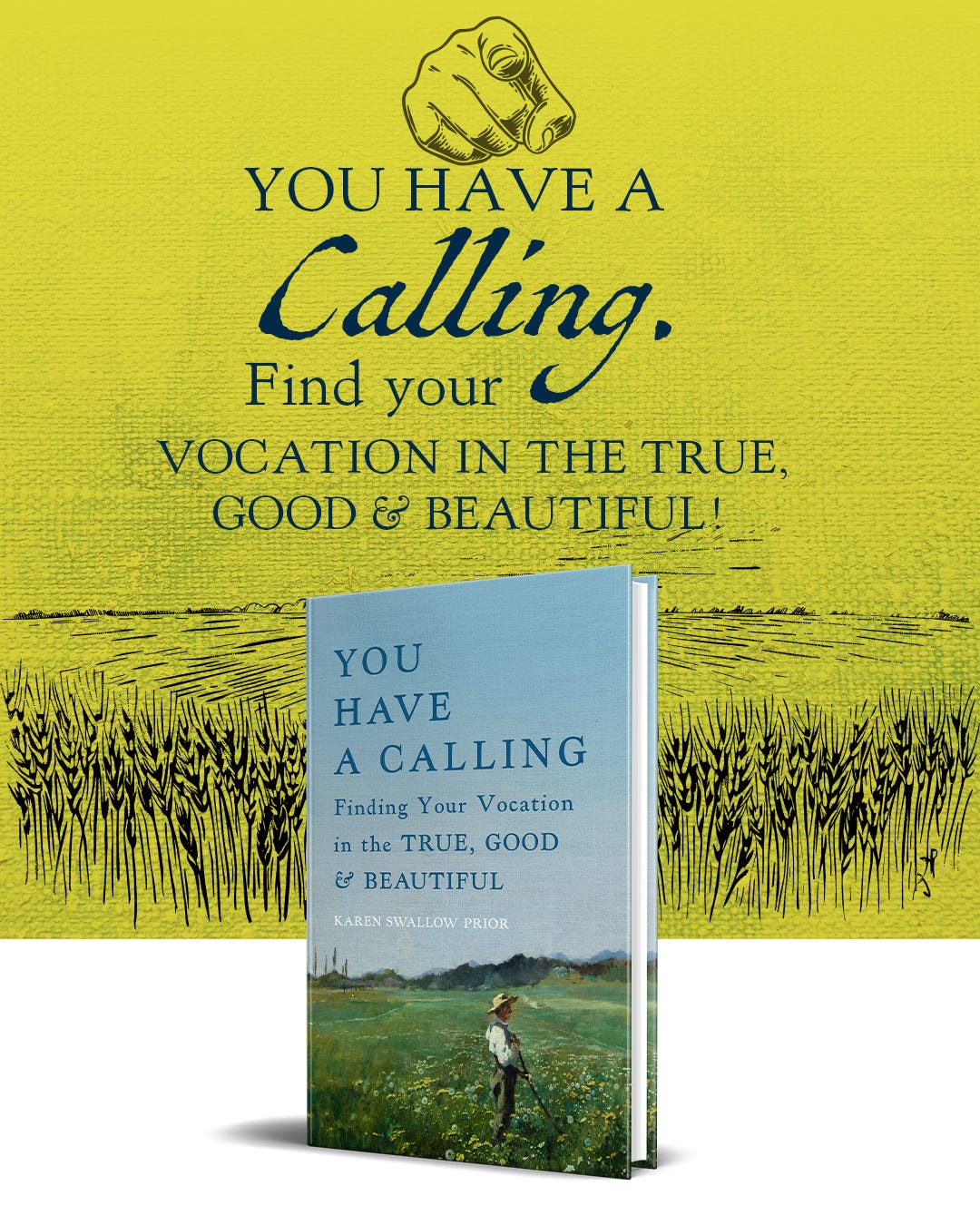

More about my new book (and a little video from me!)

PRE-ORDER You Have a Calling between now and Aug. 4 and gain immediate electronic access to the book through NetGalley by clicking the image above or here . (You will still receive the beautiful hardbound copy at release time. And may I repeat? It is beautiful!)

Pre-order between now and August 4 and you can register for a free Zoom call with me discussing the book to be held on August 4 at 8 p.m. ET.

Consider You Have a Calling for your small group or classroom!

Discounts are available for bulk orders of 10 or more copies. See details here. Or contact Adam Lorenz of Brazos directly if you need special arrangements for your school or organization. He will set you up: alorenz@bakerpublishinggroup.com

A free, downloadable discussion guide will be available when the book is officially released Aug. 5

You Have a Calling is a perfect book for high school seniors, college students, early-career folks, and mid- or late-career veterans — all stages of life — because we all have various callings at various stages of life. You, yes, you, have a calling!

(It’s also perfect for reading, contemplating, and marking up on your own, too—just a note for all my introverts out there.)

I am really excited about this book. I wrote it during a time of professional, personal, and spiritual transition. I hope and pray it serves you in reading it as much as it did me in writing it.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

John Bunyan, The Pilgrim’s Progress. Oxford World Classics. W. R. Owens, ed. (Oxford University Press, 2003), xxxi.

The ruffians don’t just physically accost the women, but they try to seduce them with their words, basically promising them a “good time” which they strenuously refuse. Christiana and Mercie consider themselves to be victorious in overcoming both the physical danger and the moral one (even though they clearly were not tempted).

Notably, Christiana promises to share her goods in common with Mercie and also contends for her faith at the Wicket Gate.

"For that many there be that pretend to be the King's Labourers and that say they are for mending the King's High-way, that bring dirt and dung instead of stones, and so marr,instead of mending."

Really enjoying this series, thank you Karen. Seems to me that Bunyan, maybe without realizing it, has written a sort of theology of the body (JPII). Christiana’s journey is the Church’s journey, not as an institution, but as a living, breathing, stumbling bride. The celestial city is not a destination beyond the world, but the world itself, redeemed.

Might I suggest the interplay between Christian’s solitary pilgrimage and Christiana’s communal journey is an unwitting icon of the incarnation’s particularity. For if Christ’s divinity was clothed in flesh, then the spiritual is never abstract, never disembodied, but always mediated through the tangible… through bread, through wine, through the laughter of children, through the sweat and terror of fending off assailants. Christian’s path was one of existential crisis, but Christiana’s is sacramental, her salvation is worked out in the company of others (as others have commented), in the domestic, the mundane, even the grotesque.

The city is reached not by transcending the body but by sanctifying it. The near assault on Christiana and Mercie is not merely an allegory of temptation but a brutal reminder that the pilgrimage is enfleshed. The divine is encountered not in spite of the body’s vulnerability, but through it. Just as Christ’s wounds remained after the resurrection, so too does the pilgrim’s journey bear the marks of struggle. Not as shame, but as witness.

Great-heart is more than a pastor, he’s an icon of Christ the bridegroom, armed not just with sword and shield but with tenderness. When Christiana’s heart bleeds in remembrance of Christ’s bleeding, she participates in the stigmata of devotion, a mystical union where love is both wound and balm. This is no mere emotionalism, it is the eros of the Cross, the divine ache that transfigures suffering into communion.