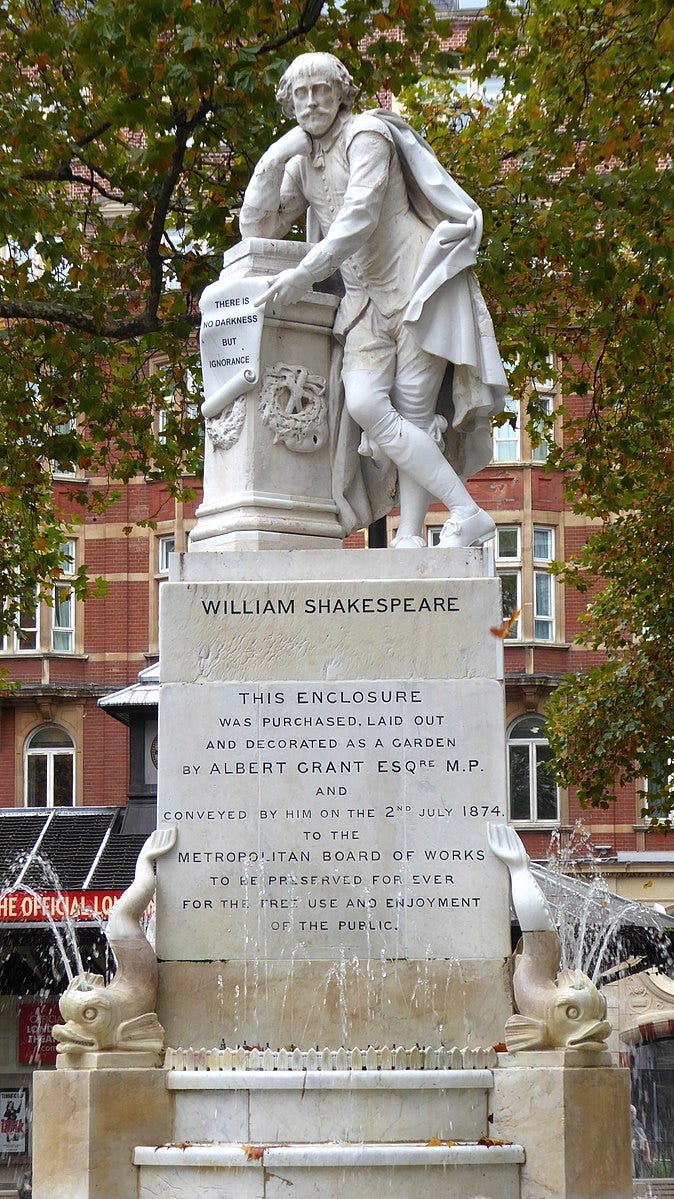

[Photo credit: Ethan Doyle White at English Wikipedia]

Sonnet 55 makes a nice follow-up to last week’s discussion of the English (or Shakespearean) sonnet form in general and Sonnet 18 in particular.

Here is Sonnet 55 (and here, too, is a lovely reading of it on YouTube, which I encourage you to listen to):

Not marble nor the gilded monuments

Of princes shall outlive this powerful rhyme,

But you shall shine more bright in these contents

Than unswept stone besmeared with sluttish time.

When wasteful war shall statues overturn,

And broils root out the work of masonry,

Nor Mars his sword nor war’s quick fire shall burn

The living record of your memory.

’Gainst death and all-oblivious enmity

Shall you pace forth; your praise shall still find room

Even in the eyes of all posterity

That wear this world out to the ending doom.

So, till the Judgement that yourself arise,

You live in this, and dwell in lovers’ eyes.

Within Shakespeare’s 154 sonnets are a number of recurring themes: love, beauty, art, time, and mortality. Nearly all of the sonnets are addressed to someone (usually just “you”), most frequently a young man, other times a woman, but the sex of the person addressed is usually (not always) irrelevant to understanding the sentiments of the poem.

The basic gist of Sonnet 18, as we saw last week, is that the beauty of the beloved surpasses that of a summer day in being, first, more virtuous (or moderate) and, finally and climactically, more eternal—that eternality owing to the immortality bestowed on the beloved by the poem itself.

Sonnet 55 picks up, in a way, where Sonnet 18 leaves off by beginning, right out of the gate, in talking about art, distinguishing between forms of art: monuments (think of statues and gravestones) and poetry. Monuments, made of marble or gilded with precious metal, seem, from within the limited scope of mortal human experience, to be immortal and eternal, don’t they? After all, they can and do exist for hundreds or even thousands of years! It takes great forces, whether of humanity (with our “wasteful war”) or nature (and its passage of “sluttish time”) to destroy such objects.1

[Photo credit: By Infrogmation of New Orleans - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=59237773]

But poetry—such as, for example, “this powerful line” (line 2) and “these contents” (line 3)—is made of even stronger stuff than stone.

Once written down and sent out into the world, written words cannot be destroyed in the same way that material objects can decay, be smashed or overturned, or be smeared by dust and time. The written word is more eternal than earth and rock because it exists in spirit not merely matter. By being immortalized in these lines of poetry (as we also saw in Sonnet 18), the “you” being addressed in this sonnet will outlive even marble statues and shine even more than monuments made dull and dusty by time (not to mention by statue rubbing, which is so much of a thing that an entire Wikipedia page is devoted to the subject).

In the classical tradition (particularly the pagan classical tradition), art is seen as a source of immortality, for it can last and often does last, seemingly, nearly forever. In the absence of an eternal, transcendent, all-powerful God, not much else besides art can come close to immortality within this world. Shakespeare inherits this classical tradition. He is writing within the Renaissance, after all, which is named for the re-birth of classical art and literature that burst onto the scene during these years.

But Shakespeare was also living in a Christian culture, and we will often see these two traditions playing out side-by-side. The Christian worldview undergirds everything Shakespeare writes, including his last will and testament, which opens with his profession of faith in Jesus Christ:

In the name of god, Amen. I, William Shakespeare of Stratford upon Avon in the county of Warwick, gent., in perfect health and memory, God be praised, do make and ordain this my last will and testament in manner and form following, that is to say, first I commend my soul into the hands of God my creator, hoping and assuredly believing through the only merits of Jesus Christ my Saviour to be made partaker of life everlasting, and my body to the earth whereof it is made.

It's worth reading the entire will—so touching, so human, so aware of our mortality and the importance of ordinary possessions that make life easier in this world: money, a bed (left to his wife), and a silver gilt bowl (left to his daughter), among other things. Shakespeare does not upon his death seem mindful of all the monuments that will be made of him—those of stone or paper.

Last week we talked about the meter and rhyme scheme of the English sonnet form. But with Sonnet 55, I want to point out how effectively a master like Shakespeare uses, in addition to these, word order.

We might think a rhyming poet arranges the first line in order to end with a word that can easily match with a rhyme two lines later. And maybe that’s part of Shakespeare’s method. But pay attention to the powerful effect this sonnet achieves simply by starting with the word “not.” “Not marble nor the gilded monuments” … (Please read this line, or better yet, all of it, aloud!). What powerful meaning (not just sound) is rendered in beginning with that emphatic not. It takes such a skillful poet to manage not only rhyme, not only meter, but also the mere order of words so as to convey the meaning so powerfully. (This is why I don’t write sonnets, or much poetry, really—I do not have the skill!)

Then, add to all this artistry Shakespeare’s gorgeous, sonorous use of alliteration and consonance throughout: marble, monuments; princes, powerful; shall, shine; unswept, stone, besmeared, sluttish (this line might be by favorite—read it out loud, for real!). And what an image of time conveyed by that word “sluttish,” one that suggests dirtiness in both the state of being unkempt and of being unfaithful. Time is but a betrayer within the grand scheme of all that is eternal, lasting, and significant.

Here Shakespeare begins to hint at the Christianity that is the basis of his worldview and that seeps out by the sonnet’s end.

Most of the poem is a memorial to the limitations of human achievement: of princes, of manmade monuments—and even the limitation of a pagan god like Mars and his human likenesses who imitate him through acts of war. These finite efforts are powerful enough to wear this world out. But only until “the ending doom.” “Doom” comes from an Old English word that means “judgment.” (Likewise, “doomsday” means “judgment day.”)

What happens in the couplet—which, as we discovered in last week’s post, offers a turn in thought or emphasis called a volta—is that the seeming immortality the speaker declares has been bestowed upon the lover through these eternal lines lasts only until judgment day. For on that day—this is implied, not stated in the poem—seeming immortality becomes actual immortality: it is the day of arising into eternity.

Until then, the beloved has these words—and the eyes of those who read the words, and love the words, who make the words shine more brightly simply by reading and attending to them as we are right now.

Shine more bright, beloved, shine.

***

Last week I suggested we might cover two sonnets a week. What was I thinking?!?! Maybe that might happen one of these days? I don’t know. It didn’t happen this week. And I begin a lot of travel for a few months, so we may continue at this more leisurely pace.

In writing this week, I realized how hard it is to write about short, powerful works when I have spent years teaching them in an in-person, embodied way, where we read the work together, pause over words and sounds and images, and have spontaneous discussions about whatever strikes whoever is in the room. I recall one class that we spent doing a very close read of an Emily Dickinson poem; I had each student present on a single word in the poem. Remembering what teaching that way is like and how I lost it has made me sad again.

But I’m so very grateful for the chance to find a new way to teach what I love and even more grateful for those of you willing to come alongside and not only be taught, but to teach me, too. Thank you, dear readers.

Up next in coming days: Sonnets 73, 116, 130, and 138.

***

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.” – Simone Weil2

Of course, I cannot help but think of the debates today over monuments to great wrongs in our history and what we do about them. Perhaps Robert E. Lee was right about one thing when he expressed the wish not to have a monument made to him. Oh, Shakespeare was prescient!

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

This article I just saw addresses nicely Kevie’s comment above. Actually, the article offers multiple ways to dig in deeper into the language of poetry and its ambiguities. Enjoy! https://www.themarginalian.org/2023/02/18/robert-bringhurst-poetry/

What a great Sonnet 55 is, and yes, a gorgeous follow-up?, echo?, refrain? on Sonnet 18. Thank you for linking the two and offering such robust and intriguing comments on them.

A friend, Tracey Finck, and I are reading through T.S. Eliot's "Four Quartets" as well as the line-by-line commentary on them, "Dove Descending" by Thomas Howard. Howard notes the time it takes to share the magic and mystery of poetry by means of prose, just as you mentioned in your column, Karen. Prose, he points out, has to work very hard to describe poetry. There is so much packed into very few words in a poem, but to write about what is going on at the heart of it takes a lot of time and effort and words. Or as Howard says, "Prose has to prowl about the outskirts (of the poem), like a guide with his bunch of tourists."(p 57 )

Thanks for taking us on this magical mystery tour of Shakespeare's sonnets, Karen.