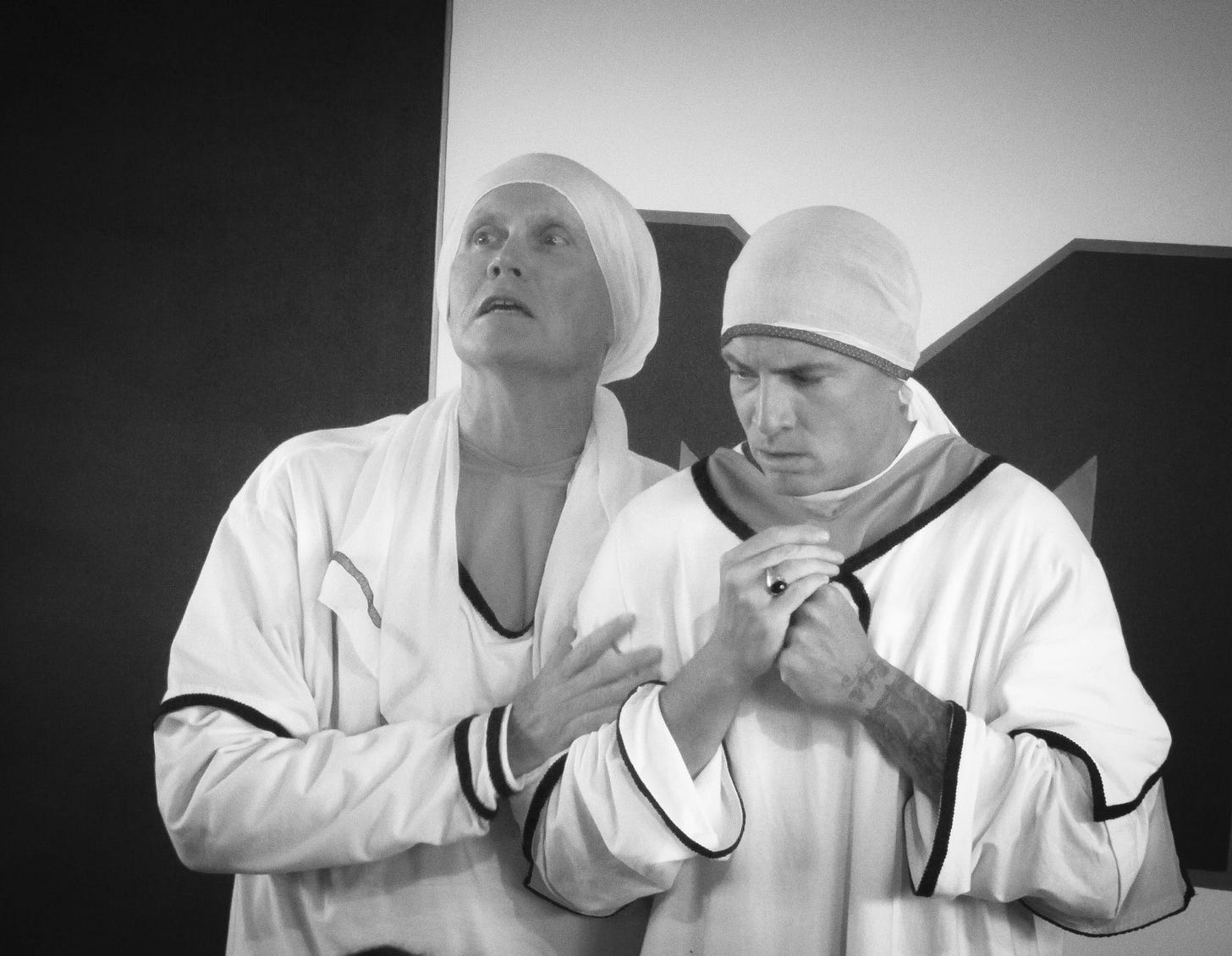

[Photo credit: Shakespeare Behind Bars 2012 production Romeo and Juliet, Luther Luckett Correctional Complex LaGrange, Kentucky; Photographer credit: Holly Stone (used with permission)]

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.” – Simone Weil1

Note: It’s my delight to have a guest post this week from Shakespearean scholar and friend of The Priory, Jack Heller. More information on Jack is below. We’ll have “spring break” next week. (I may or may not get around to writing something or other on other topics.) Our next readings will cover Christopher Marlowe’s The Tragical History of Dr. Faustus. It is online here, and you can also buy a print copy for just a few bucks here. I will plan on spending two or three weeks on this play, but it’s not a long read.

***

In August 2011 I spent a week visiting the Luther Luckett Correctional Complex in La Grange, Kentucky, to conduct a week-long seminar on Romeo and Juliet. The Shakespeare Behind Bars (SBB) men would begin rehearsing in September for their 2012 performance of the play, and I was introducing the play with a discussion of an act per day. On Wednesday, we were at Act 3, scene 1, where the violent undercurrents of the play boil over: Tybalt kills Mercutio and Romeo kills Tybalt.

I came to Shakespeare as an English major, scholar, teacher, and frequent play-goer; at the time, I had no previous directing or acting experience. The incarcerated theater company had a mix of those who had been performing Shakespeare for as many as 15 years and those who were reading and struggling to understand Shakespeare for their first time.

Our discussion of Act 3, scene 1 turned towards the SBB men recalling the circumstances of crimes they had committed—the rashness, the fear, the hatred, the surprise, even the bloody mess.2 This was my first time ever having my teaching leading to a discussion of those kinds of life experiences—a revelation to me of how else a person may encounter a Shakespeare play.

I had first heard of Shakespeare Behind Bars from a 2005 documentary of the same name.3 It follows the prison program through its 2002-2003 season as the men had prepared to perform The Tempest. The viewer sees the rehearsal process, joy, determination, grief, painful honesty, even an occasional theological discussion. In response to Prospero’s closing lines, “As you from crimes would pardon’d be, / Let your indulgence set me free,” an actor wonders what redemption means when one’s sin is even repulsive to oneself. The movie closes with scenes from the play’s performance.

After watching the documentary, I began attending SBB performances in 2007 of Measure for Measure. Thereafter, I began to visit regularly to observe rehearsals, to discuss the plays, and to have my university students meet the men taking Shakespeare and their own lives seriously. In 2010, I started the week-long seminars for the SBB men with The Merchant of Venice. I did these until 2019, with the outbreak of the pandemic preventing the workshops ever since.

During one of the student visits, I asked the man who was playing Juliet to tell my students why he had chosen the role. Derald Weeks was 33, bald, and covered in tattoos. He is serving a life sentence for a murder he committed while involved in the Aryan Brotherhood. He told of being raised in an environment of hatred and that he had never known what love is. So he chose to perform Juliet so that she could be his “mentor for love.”

It seems that Juliet did indeed serve as a mentor for love for this one-time White supremacist: Several months later, when the men performed the play, he collaborated closely with an African-American actor who performed the role of Friar Laurence.4

In 2013 I asked the SBB men if they thought that I had what it would take to be the lead facilitator of a prison Shakespeare program. They gave me great advice overall, but the most important was to listen — listen to the men, the actors, the participants. Listen. Incarcerated people do not have control over their lives, input into opportunities, options they can choose or reject. I should listen because listening is the baseline for affirming their humanity.

In mid-August I contacted the administration of Indiana’s Pendleton Correctional Facility, a maximum-security prison about 30 miles northeast of Indianapolis. We arranged a first meeting for Shakespeare at Pendleton in October 2013. I wanted to hear from the participants what they would like for the program to be, and it soon was clear that they wanted to try acting in a play. By November we had a conversation on what kind of Shakespeare play they would like to perform. I asked them about their fears, their ambitions, what they wished they had had an opportunity to do. Of course, they did not know most of Shakespeare’s plays, but I told them that I would match plays with their answers, and we would find and choose a play together. We landed on one of Shakespeare’s lesser-known plays, one which to my knowledge had never been performed in a prison or by incarcerated actors before: Coriolanus.

Coriolanus is about a proud Roman soldier, Caius Martius, who is incapable of controlling his temper. Paradoxically, some of his behavior may seem humble, but this is only because he does not believe anyone is worthy of praising him. Martius has political opponents in Rome and military opponents in the Volscian army from the city of Corioles. He gets the name Coriolanus in Act 1 when he defeats the Volscians single-handedly. Coriolanus raises many questions about the (self-) destructiveness of locating masculinity in anger and in violent prowess. Volumnia, Caius Martius’s mother, has the most direct statement of a theme for the play: “Anger’s my meat. I sup upon myself / And so shall starve with feeding” (4.2.68-69, Folger edition).

We spent 18 months working on understanding the play, developing a text we could perform in about an hour (the men chose most of the scenes), rehearsing, developing costumes (color-coded t-shirts) and weapons (cardboard swords), and bringing the play into a shape we wanted. Because at the time I still had no acting and directing experience, our effort had to be collaborative, and I was especially proud of the actors’ own inventiveness in creating their characters and the sets.5 Finally, on April 23, 2015, Shakespeare at Pendleton had its first performance with an audience of about 100 incarcerated men, a film crew then making a movie at the facility, and 20 outside guests.6

Shakespeare at Pendleton went on to perform three more plays. In 2017 we did the Dogberry scenes from Much Ado about Nothing and the scenes with Bottom and the actors from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. We were prohibited from presenting Dogberry as a police officer, so we presented him as a Black Pentecostal Baptist preacher leading a neighborhood watch. This worked surprisingly well in drawing out Dogberry’s quirky use of theological language. In 2018 we performed Timon of Athens, another first-time for a performance in a prison. This play involves a lead character who thinks he has endless wealth until he loses everything and dies in exile. I was struck with how resonant this play was to the men who used to have good lives before they got into trouble. We struggled to get this play done because the summer of 2018 was hot and violent inside the prison; we had lockdowns up to the day before our scheduled shows, and yet the men remembered the work they put into it beforehand and gave two successful performances. Our fourth play was composed of scenes and monologues from a variety of plays, and a second half of performing the third act from Thornton Wilder’s Our Town. We did this monologues show to introduce more of Shakespeare’s range to the participants, and the act from Our Town deals with other losses the men have known in separation from their families.

We were about four months away from having a performance of Julius Caesar ready when COVID struck in 2020. We officially discontinued Shakespeare at Pendleton in 2022, though I am exploring beginning a readers’ group program soon at the same prison.

What is the purpose, or the value, of having a Shakespeare program in prisons? I do not think a person can program how the participants may benefit from performing Shakespeare. I know that it helped the actor who performed Coriolanus to deal with some of his own anger issues. I know that the actor of Timon was praised by prison administrators for carrying through with his commitment to seeing the play done. I know that several men for whom English was not their first language developed more confidence in their communication. Several men were able to contribute their artistic talents to set and costume designing.

All of these have been dramatic results from the Shakespeare at Pendleton program, but two comments from participants capture all the justification that a Shakespeare program needs. One said that he felt free when he was performing Shakespeare. And our actor who performed Sicinius in Coriolanus wrote, “I’m of the mind now that, if my life is anything less than the autograph of my soul . . . then I’m wasting my time. And the people I fellowship with here make the time well worth it.”

Prison Shakespeare helps participants to write new autographs of their souls.

***

Jack Heller retired in 2023 after 21 years as an English professor at Huntington University in Huntington, IN. He specialized in English literature up to 1800, Shakespeare and Renaissance drama, and African American literature. He authored one book on the English dramatist Thomas Middleton, Penitent Brothellers, and a few articles on Shakespeare, including one on Dogberry in Much Ado about Nothing and one on the sacraments in Julius Caesar (not online). Heller has also done an online video interview with Jessica Hooten Wilson about Ernest Gaines and his novel A Lesson before Dying. If you would like a copy of the Caesar essay or otherwise want to contact Heller, you may reach him at jack.heller62@gmail.com.

***

Again, here’s the essay I wrote on Shakespeare Behind Bars a while back at The Atlantic.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

Shakespeare has many scenes in which live actors become “corpses” needing to be removed from the stage. Hamlet jokes about this after he kills Polonius.

This documentary is still widely available on streaming platforms, and I highly recommend it. A viewer should be aware that the men do discuss the crimes for which they were incarcerated, which include sex offenses and murder. I would suggest that the movie would be appropriate for viewers 15 and older.

Following the pandemic, SBB did a retrospective for their 25th season in 2023. I have not yet resumed working with them, but I hope to attend their upcoming performance of As You Like It in April 2024.

Along the way, the men were profiled in an online National Geographic article about Shakespeare in prisons: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/140428-innovator-laura-bates-prisons-solitary-confinement-shakespeare

The movie the film crew was making, O.G., was shown on HBO and had a number of the Pendleton Shakspeareans as extras in the cast. These actors also feature prominently in the accompanying documentary It’s a Hard Truth, Ain’t It. The lead actor in O.G. is Jeffrey Wright, the Oscar nominee from this year’s American Fiction; he attended the performance of Coriolanus.

I would like to post here a comment I posted on my Facebook page to introduce the article:

For the most part, I have avoided using men's names in this article, for two reasons. First, I believe I have used comments made in shareable contexts, not in contexts calling for confidences. In other words, the comments were intended to be known by others. However, the men themselves, the commenters, do not have a "public" to which they are answerable. Some of the people I have mentioned, sometimes by character names, are now out of custody and are living good, and private, lives. I do not want to out anyone as a formerly incarcerated person, to call attention to their pasts.

Secondly, states have various victim notification requirements. I want to avoid crossing those requirements, especially since I am working on returning to volunteering in prisons.

Where I have used a name, his name has been publicly associated with his comments. This is also true of the use of the picture accompanying the article, which has been used with permission.

To the men whom I've worked with who are seeing this in freedom: It has always been my privilege--one of the fullest privileges of my life--to have worked with you and to have gotten to know you. If you recognize yourself in this essay, if you wish to be known, you may introduce yourself. Otherwise, though, know that I remain ever grateful to you.

I really enjoyed learning about Shakespeare Behind Bars; thank you! I took a Pen Project Prison Teaching course in grad school in which we would give incarcerated men feedback on their writing, especially poetry, and I found the whole experience very meaningful. I’m so glad to know there are opportunities like SBB available for incarcerated men to participate in the arts.