Paradise Lost: Book 9

"He leading swiftly rolled in tangles, and made intricate seem straight."

Well. Here we are. We have finally arrived at the climactic moment in Paradise Lost and in the story of the fall that it re-creates. It has taken eight books to lead up to this moment, and we will have three books following it. Milton has laid out quite a journey.

Here’s a little recap: We begin in Hell with Satan and his minions rousing themselves after being cast down following their rebellion against God and defeat by his armies in Heaven. We then observe God on his throne in Heaven seeing it all, foretelling the fall of humanity and, more importantly, the means of redemption he already has in place for them. Satan finds Adam and Eve in Eden, wrestles with regrets but allows his hatred and desire for vengeance to rule. He plots while God’s ambassadors, angels Gabriel and Uriel, attempt to defend the first humans. Satan visits Eve in a dream, one that foreshadows the temptation and fall that will come. God sends Raphael to warn Adam and Eve of the dangers they face to give in to temptation and disobey God and to remind them that they have free will to choose to obey or not. Adam asks Raphael how disobedience entered the world. Raphael tells the story of Satan’s jealous rebellion upon learning from God that God had a Son who would rule with him. Once again, Raphael warns Adam of the temptations he will face to disobey. Then he tells Adam and Eve the beautiful story of creation. Adam and Raphael discuss the different kinds of love: Adam’s love for Eve is sensual. Raphael describes a spiritual love among the angels that transcends the physical expression of love. I think it is significant that this discussion of love (inscrutable and strange as it is) closes these first eight books and brings us to the temptation and fall.

As Dr. Cardenas mentioned in his essay last week, when Paradise Lost is taught in introductory-level college classes, the whole work is seldom included. (You can see why, I’m sure; there would be no time for anything else!) But certain sections are almost always included and excerpts from Book 9 always make the cut. Of course, it conveys the most famous part of the biblical narrative. Beyond that it exemplifies how creative Milton gets in expanding on the original text. But it’s not only sheer imagination and artistry at play here—there is also theology, anthropology, and tradition. It is these three things that I think we might criticize most in Milton. His poetic skill, his classical and biblical knowledge, and his artistry are nearly unmatched. But that does not mean he is untethered to the biases of his time and traditions. Nor are we immune to those continued influences.

As a timely case in point, consider the recent decision by the translation committee of the English Standard Version Bible to reverse course on their translation of Genesis 3:16, the verse in which God lays out the consequences for Eve for her sin. (This is getting ahead of the narration of Paradise Lost but is relevant to the narrative license Milton takes in portraying the fall itself.) This Christianity Today article by Wendy Alsup explains that when the ESV was released, this verse was translated in the same way as other major translations:

To the woman he said,

“I will surely multiply your pain in childbearing;

in pain you shall bring forth children.

Your desire shall be for your husband,

and he shall rule over you.” (Genesis 3:16 ESV)

But in 2016 the ESV changed the translation from Eve’s desire being “for” her husband to being “against” her husband. The article gives a good history of what led up to this sudden change, but I don’t think I need to explain to you what a vast difference there is between those two words and, more importantly, their implications for relations between husband and wife and man and woman. But then, just like that, the committee changed it back not even ten years later. (Here’s the committee statement on why).

I’m no translator or expert on Bible translations. I do know that the best translators do their best to balance the demands of the original languages with current day meanings in the languages into which the originals are being translated. It’s work that is both art and science. The point is that we carry our biases, customs, and traditions into that work because language does the same. And Milton does, too.

His poem should be read not as gospel truth but as poetic wonderings. Might it have been like this? Might it not? If not, what assumptions or traditions is Milton bringing into his poem that not only aren’t in the Bible (most of it is not, obviously), but that also might contradict the Bible? We’ve discussed some of these contradictions along the way, readers, but Book 9 is where it all gets very fraught, I think, a tension very much confirmed by this very recent dust-up in ongoing Bible translation.

I’m not expert enough in Milton nor knowledgeable enough in the traditions of biblical interpretations to locate the sources of Milton’s views, let alone affirm or refute them, but here a couple of big ideas in Book 9 that I think are highly interesting and debatable.

First, was Eve alone when Satan tempted her? As I understand it, there are three basic schools of thought: Adam was there and didn’t stop her, Adam wasn’t there and Eve went to him after the fact as Milton portrays, or he was nearby but not close enough to see or hear what was happening. All these interpretations can be supported by the actual biblical text which reads in Genesis 3:6 that Eve gave the fruit to her husband “who was with her” (but at which point he was with her, exactly, is not definitive).

Milton obviously goes with the interpretation that Eve was working apart from Adam. He makes it her idea, one that Adam is reluctant to agree with. In this, is Milton assigning more or less blame to Adam? Does Adam fail to lead Eve as strongly as he should? Eve says so in lines 1155-56 when she asks Adam why he didn’t as “the head command me absolutely not to go”? And so they both, now fallen, descend into the blame game, arguing and disputing, insulting and name-calling (“ingrateful Eve,” Adam calls his wife in line 1164).

As I’ve mentioned before, Milton had his work cut out for him in trying to portray a pre-fallen world and pre-fallen people (none of us can really imagine it). But he does get the post-fallen condition right.

He gets it right but one might quibble with his emphasis. I’m not sure if I quibble or not, but the fact is that Milton uses the sexual relationship between Adam and Eve as the locus of the sharpest contrast between pre-fallen and post-fallen state. The biblical warrant for this might be found in the fact that their immediate shame is felt by them in their nakedness. Of course, not all nakedness is necessarily sexual, but tradition has made this the interpretation. Another way of understanding nakedness is as more general vulnerability but that understanding doesn’t show up in Milton or many places that I’m aware of.

Instead, we have sex.

Milton sharply contrasts Adam and Eve’s pre-fallen consummation in the garden bower described in Book 4 with the lustful passion that consumes them immediately (well, Adam more specifically) after they have eaten the fruit. Adam is inflamed by carnal desire and casts on Eve “lascivious eyes” which she as “wantonly repaid” (1013-15) and they soon become “wearied with their amorous play” (1045).1

On a human level (one played out over and over in this fallen world), it makes sense that the most immediate and dramatic consequences of the fall would manifest in sexual activity. But I don’t think this is supported directly by the biblical text (any more than the biblical text supports the consequences of the fall being that Eve’s desires would be “against” her husband rather than “for”).

Perhaps we fallen people can’t help but read backwards onto the biblical text through the lens of our fallenness—and our own struggles.

Interestingly, Milton has Adam consume the fruit out of his adoration of Eve and his desire to be with her. Because they are one flesh, Adam says to Eve, “to lose thee were to lose myself” (959).2 He is “fondly” (foolishly), the poem says, “overcome with female charm” (999). Is this an indictment of Adam? Or Eve? Of men? Of women?

I can’t help but think of Milton’s scandalous (for the times) argument in favor of divorce—of his own disappointment in marriage, separation followed by eventual reconciliation. I read Book 9 not as theology but as anthropology. And perhaps a bit of autobiography. And definitely as poetry. Sheer poetry.

I also can’t help but keep going back to what Milton seemed to be trying to point us to in Raphael’s description of a divine union that is not the sex that Adam and Eve know but that neither they nor we can comprehend in this earthly state.

Ultimately, Paradise Lost is human and not divine.

With all that said, before concluding this week’s post, let me point out a couple passages that I think are divine poetry:

Eve agrees to let Satan take her to the tree:

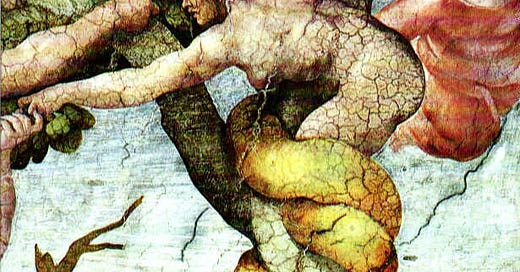

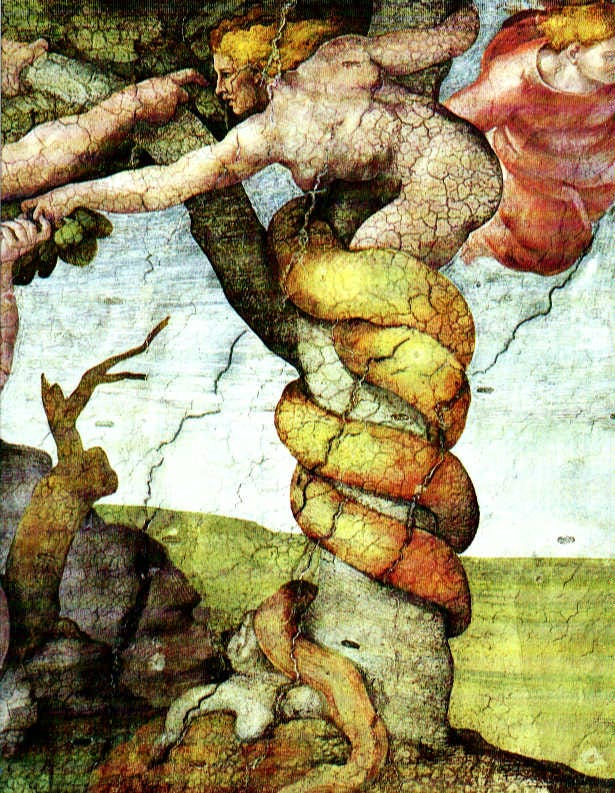

Lead then, said Eve. He leading swiftly rolled

In tangles, and made intricate seem straight,

To mischief swift. (631-33)

Eve eats the forbidden fruit:

So saying, her rash hand in evil hour

Forth reaching to the Fruit, she pluck'd, she eat:

Earth felt the wound, and Nature from her seat

Sighing through all her Works gave signs of woe,

That all was lost. (780-84)

The last lines of Book 9 (what a pun!):

Thus they in mutual accusation spent

The fruitless hours, but neither self-condemning,

And of their vain contest appeared no end. (1187-89)

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”3

WHAT’S AHEAD:

Book 10 of Paradise Lost will be a guest post from Alan Jacobs. You can check out his writing here.

I was wondering if there would be interest in having a Zoom meeting for paid subscribers when we wrap up Paradise Lost? I know it would be impossible to pick a time that would work for everyone. And I have to figure out the best way to communicate it once I do. (I know it’s theoretically easy, but that’s not the same as actually easy for me!) Anyway, might you comment, readers, and let me know if you’d be interested in a celebratory chat when we are done?

We will read The Pilgrim’s Progress together in coming weeks! We’ll rest a bit after finishing Paradise Lost. But if you want to plan ahead, you might consider getting a good edition for yourself. As the second most published book in the world (after the Bible), there are many. One word of caution is that many of these are redacted, abridged, and modernized—so there are great variations. This is the old copy I use, from Oxford World Classics. I’d say you are safe with any unabridged edition with original marginalia (and editorial notes also help). Note that some editions are modernized and take various liberties in so doing.

C. S. Lewis, ever squeamish about sex, did not like this turn in the work. In A Preface to Paradise Lost he calls this “one of Milton’s failures” (161).

Yet, as any brave widow or widower can attest, this is a lie. It might feel true, but it is not.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

A quick missive. I immediately went to Bonhoeffer's "Creation and the Fall" in order to see how this Christian thinker dealt with the issue of Eve. The gist is that Eve is taken from Adam and then given back to him. Adam's fall will become complete as soon as Eve takes the fruit; but Eve's fall is also brought to completion with Adam's rebellion.

Now here's the thing. Adam and Eve are freely given to one another out of God's compassion. (Milton's non-Trinitarian theology would have blinded him from this, and, as the guest from earlier pointed out, solitude is considered a beautiful thing for the independent thinking Milton.) In any case, neither Adam nor Eve work or want for one another; they are simply given one another because God says it is not good to be alone (this is the first time God declares something to not be good that we know of). The Fall begins when human beings believe they must take. And, reunion is only restored when human beings can once again receive a gift from God which will make them whole.

The late Tim Keller noted that the difference between a contract and a covenant is that the former occurs when the two parties enter into an agreement based on what what they can get from the other; while a covenant occurs when one or both of the parties is focused on what they can give to the other. As Bonhoeffer states, "The theological question is not a question about the origin of evil but one about the actual overcoming of evil on the cross; it seeks the real forgiveness of guilt and the reconciliation of the fallen world." The point of the Christian faith isn't an insight we glean or a work we perform; but a gift we receive.

There are so many things worth mentioning in Book 9! Here's Satan on entering the serpent:

"O foul descent! That I who erst contended with Gods... am now constrained into a beast, and mixed with bestial slime" (163-5). And then: "But what will not ambition and revenge descend to? Who aspires must down as low as high he soared, obnoxious first or last to basest things." (168-171)

How often do we see this played out, where naked ambition makes people descend into the depths of slimy corruption in pursuit of whatever drives them: money, power, fame, sex.

I was also taken by this very modern-sounding line from Eve, after eating the fruit and becoming "enlightened," who calls God "our great Forbidder" in line 815. And isn't that how God has been portrayed these days? He is a Killjoy. He suffocates us with his rules. He robs us of our freedom to be our best selves! Milton is prescient.