Readers, I’m thrilled this week to bring you the insights of a true Milton scholar, Manuel Cárdenas. Dr. Cárdenas earned his PhD at McGill University and was appointed Assistant Professor of Renaissance & Early Modern Literature at the University of Alberta. His current book project, 'Their Solitary Way': Singular and Communal Knowing in Milton and Cavendish, investigates the self-authorizing potential of solitude in the seventeenth century alongside nascent communal epistemologies. You can learn more about Dr. Cárdenas at his faculty page. I’m so grateful for his willingness to share his expertise with us at The Priory.

It has been my great delight as an inveterate Miltonist to follow this series as Dr. Prior has ushered you into Hell and out through Chaos, across Eden next and then towards highest Heaven to witness war celestial and the creation of “This pendent world” (PL 2.1052). If you feel dizzied by the poem’s huge swings across place and time, you are in good company; Milton himself nearly falls off his figurative high horse at the start of Book 7 (7.16–20)! This is not flaw but feature in Paradise Lost, which works with your delirium to make old things seem new, and new things seem timeless.

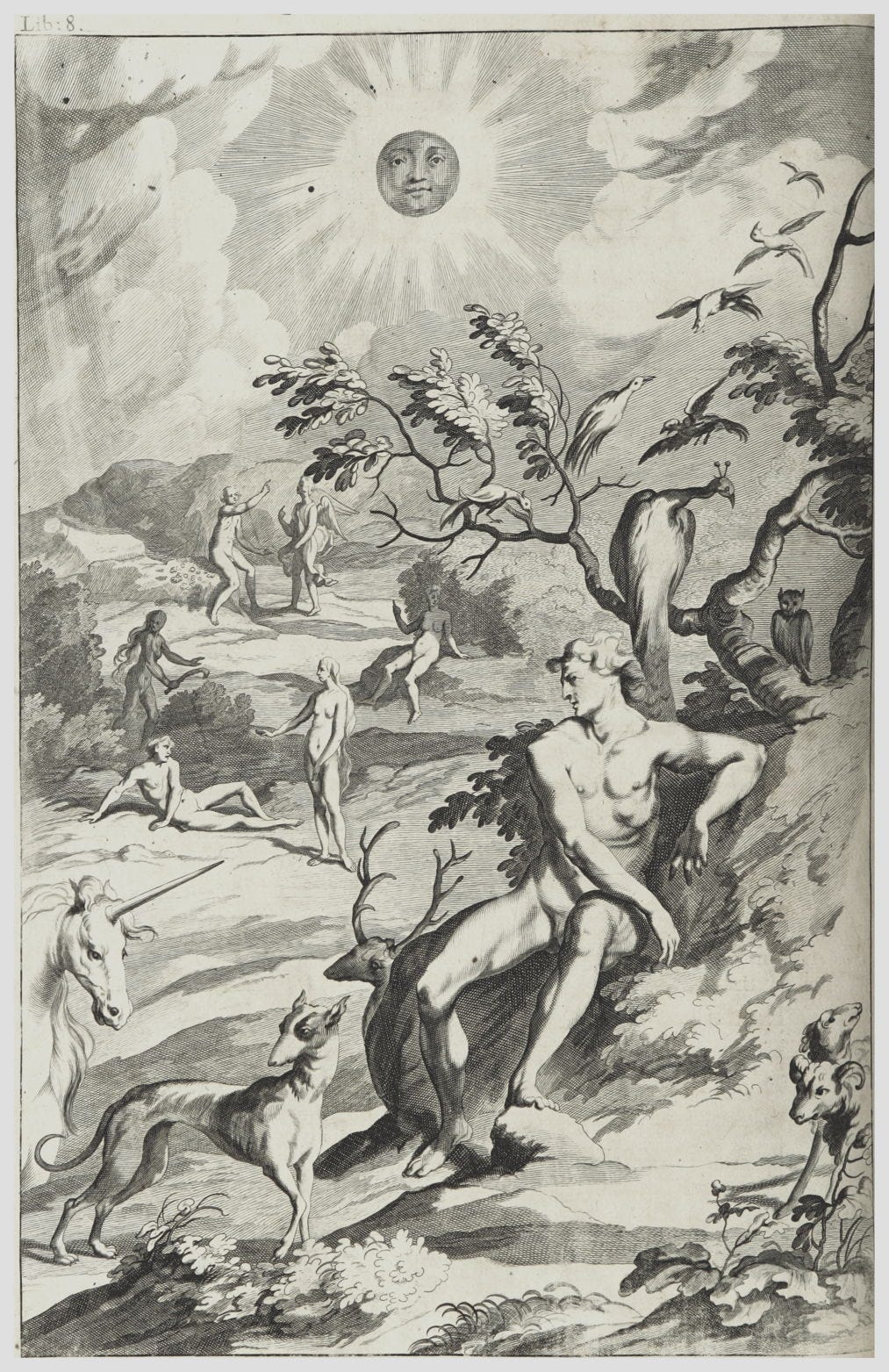

All the same, the poet knows we need solid ground, and it is in Book 8 that we may find our footing. No more talk of the essence of matter, the origin of evil, and the creation of the universe ex deo. When Adam tries to raise the pressing question of whether Earth orbits the sun or vice versa, he is gently (depending on whom you ask) denied by the archangel Raphael: “Think only what concerns thee and thy being” (8.174). This turns out to be quite a large domain. Adam, still hungry for conversation, takes the opportunity to “relate / My story” (8.204–5): the first moments of the first human, and so the story of us all.

I. “Who himself beginning knew?”

Adam’s birth narrative is freshly inventive and among the most illuminating parts of the poem. Milton this time expands on Genesis to put flesh and bones (so to speak) on Adam and God as beings who think and feel. We have here the lineaments of Genesis 2: God places Adam into the garden, warns him about the fruit of that forbidden tree, brings forth the creatures to be named by Adam, and forms out of his rib a suitable partner over whom Adam immediately rejoices. Milton’s every extension of this blueprint works towards creating psychological plausibility—to move Adam beyond figurative type into a person with a backstory and motivation.

He and Eve will fall, of course, but that fall must make sense. And despite the weight of church history and our knowledge of the story, it is not obvious how a rational creature, made in the image of God and placed into utter delight, would choose to disobey.

In my reading, Adam’s later actions have everything to do with his first experiences of the natural world and his place within it. Milton’s unfallen man is in many ways a sublime creature: humble and grateful, yet bold and curious. Satan in Book 5 poorly reasons that because angels “know no time when we were not as now, / Know none before us,” they must be “self-begot, self-raised” (5.859–60). Adam takes a more unassuming approach: “For man to tell how human life began / Is hard, for who himself beginning knew?” (8.250–51). His story is one of gradual but incomplete understanding:

As new waked from soundest sleep

Soft on the flowery herb I found me laid

In balmy sweat, which with his beams the sun

Soon dried, and on the reeking moisture fed. (8.253–56)

Adam’s earliest memories are tactile and participatory. He feels before he sees, and seems almost still to be part of the earth from which he was formed, with the sun lapping his neonatal liquid. That great light in the sky then enables his “wondering eyes” to “gaze[] a while the ample sky” (8.257–58). Springing to his feet, only after viewing the glorious scene of “hill, dale, and shady woods, and sunny plains, / And liquid lapse of murmuring streams,” and with them “Creatures that lived, and moved” does he stop to look at himself (8.262–64). Adam’s instinct is to peer outward first.

Even after perusing and surveying himself (8.267–68), he asks, “Ye hills and dales” and “ye that live and move” to “tell, / Tell if ye saw, how came I thus, how here?” (8.275–77). Adam knows he was made and wants to know his maker. He strives to know more by conversation with other created things. He does not yet know that rivers don’t talk (though they “murmur”) or that aardvark and zebra cannot speak to him directly.1 And so, when his question is met with silence, a “pensive” Adam—thus possibly “gloomy, sad, melancholy”2 —sits down once again (8.287). Made for communion, his first joyous exploration ends in uncertainty or even disappointment.

II. “In solitude, / What happiness?”

The ensuing episode is crucial to Milton’s depiction of Adam and Eve and God, though it is rarely read in university, where professors typically assign only Books 1-4 and 9. To this point in the poem God appears in heavenly glory, often as just a voice—more often than not, a commanding voice. But the “Presence divine” appears to Adam directly and presents himself as the answer to Adam’s inquiry: “Whom thou soughtst I am,” he says, in playful intimation of his later revelation to Moses (Exodus 3:14; PL 8.314–16, emphasis mine). This God takes Adam “by the hand” (PL 8.300) as Adam will take Eve. He speaks “mildly” (3.317), with the familiar “thee”/“thou” address as he shows Adam the garden prepared for him and gives him authority over all creatures. Perhaps emboldened by his creator’s generosity, Adam takes the remarkable step of questioning whether this glorious Earth is quite enough for him to be satisfied:

So amply, and with hands so liberal

Thou hast provided all things: but with me

I see not who partakes. In solitude

What happiness, who can enjoy alone,

Or all enjoying, what contentment find? (8.362–66)

Talk about approaching the throne of grace with confidence! The “vision bright” does not get defensive, but “As with a smile more brightened,” engages in a lively debate of Socratic dialogue about the nature of solitude that ends with Adam’s full happiness (8.367–68).

I could spend (and have spent) a dozen pages on the nuance of that discussion, which touches on the intelligence of animals (“They also know, / And reason not contemptibly,” God reminds Adam [8.373–74]), whether friendship exists only among equals, whether and how God’s solitude differs from humanity’s. But just as important, I think, is God’s disposition towards his creature. He gives the human space to speak and takes his ideas seriously; he asks probing questions that push Adam to develop his thought in real time. This could be a frightening moment, but God is “not displeased” (8.398) with his creature’s request or even the pushback against the divine injunction to live happily among the animals (8.374–77).

At length, the “gracious voice divine” breaks the pretence: “Thus far to try thee, Adam, I was pleased, / And find thee knowing not of beasts alone, / Which thou hast rightly named, but of thyself” (8.437–39). So it is that Adam, who knew not his beginning, through discussion with God comes to understand himself and what God already knew, that it is “not good for man to be alone” (PL 8.445; Gen. 2:18). Eve is the culmination of creation. God tells Adam she is “Thy likeness, thy fit help, thy other self, / Thy wish, exactly to thy heart’s desire” (8.450–51). The first man began life separated from his native soil, reveling in creation but finding it incomplete. He is finally satisfied with the emergence of the fellow creature whom he considers a very part of himself: “one flesh, one heart, one soul” (8.499).

III. “Where art thou, Adam?”

Adam’s longing for Eve thus predates her existence, and his first experience of solitude as aloneness or loneliness may be the source of an insecurity that leads to disobedience in Book 9. He cannot imagine a world apart from her. Eve, for her part, refuses to be seen merely as an appendage, as a part. Her desire for independence (and maybe an insecurity about being secondary or inferior to Adam3) lays the foundation for her disobedience. These are symbolic figures, of course, but Adam and Eve are individuals, too, and the proper expression of individuality between friends and lovers is one of the poem’s great questions. All the same, Book 8 and the epic more broadly make community the basis for delight.

This is true not only of humans, but of angels and even God. Raphael’s story confirms angelic dance and feast and things more intimate (see 8.621–27). Although God says during the debate that he is “alone / From all eternity” and has no second, much less an equal (8.405–7), the poem itself insists on God’s desire for community in Heaven and Earth, with the latter one day joining the former.

Some readers of this series on Paradise Lost have registered surprise that Milton’s God seems not to walk with the humans in the cool of day. In fact he does, though it’s far from explicit. When the Son (who is referred to as God in this passage) arrives after the Fall to act as “mild judge and intercessor both… walking in the garden” (10.96; 10.98), the humans hide from him. With some genuine hurt, he calls aloud:

Where art thou Adam, wont with joy to meet

My coming seen far off? I miss thee here,

Not pleased, thus entertained with solitude. (10.103–5)

Conversely, God is wont to, used to, seeing a delighted Adam running to see him, an unfallen image of that prodigal son who sees his father across the field while still a long way off. God, “not unpleased” in his earlier conversation about his hypothetical solitude, is now not pleased to be met with solitude rather than his creature.

As Book 8 draws to a close, melancholy also draws near. The hungry sun, now satisfied, has set. Adam says goodbye to Raphael “the sociable spirit” (5.221), and for the first and last time, angel has supped with man. Eve returns from her flowers and Adam returns to their bower. This night will be the last that they enjoy in full unity, a knowledge made tragic by this book’s illustration of what human life is supposed to be like. How such unity may be fractured and how loneliness and shame seep into its cracks is the subject of Book 9.

Milton knows it will be some time before God again walks the garden—in Gethsemane, then outside a tomb near Golgotha, and finally by the Tree of Life (Rev. 22). Paradise Lost and Book 8 especially might represent his best attempt to immortalize Adam and Eve’s short time walking alongside him, before they, “with wandering steps and slow, / Through Eden took their solitary way” (12.648–49).

Next week: Book 9

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”4

***

WHAT’S AHEAD:

Book 10 of Paradise Lost will be a guest post from Alan Jacobs. You can check out his writing here.

I was wondering if there would be interest in having a Zoom meeting for paid subscribers when we wrap up Paradise Lost? I know it would be impossible to pick a time that would work for everyone. And I have to figure out the best way to communicate it once I do. (I know it’s theoretically easy, but that’s not the same as actually easy for me!) Anyway, might you comment, readers, and let me know if you’d be interested in a celebratory chat when we are done?

We will read The Pilgrim’s Progress together in coming weeks! We’ll rest a bit after finishing Paradise Lost. But if you want to plan ahead, you might consider getting a good edition for yourself. As the second most published book in the world (after the Bible), there are many. One word of caution is that many of these are redacted, abridged, and modernized—so there are great variations. This is the old copy I use, from Oxford World Classics. I’d say you are safe with any unabridged edition with original marginalia (and editorial notes also help). Note that some editions are modernized and take various liberties in so doing.

At least for now; a complicating but exciting possibility in Milton’s Eden is that all creation can change and move closer to God. Indeed, nature is already animate.

The first definition of “pensive” in the Oxford English Dictionary, still current in the 17 th century.

Recall, though, that Adam asked for an equal and God said he gave Adam his exact wish. Her intelligence and verbal acuity indeed seem at times to surpass Adam’s, as critics have often observed.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

I notice some unintentional irony in the exchange from lines 540 - 594. Adam tells Raphael that he knows Eve is his inferior in mental abilities, but whenever he sees her, reason and wisdom desert him. Raphael replies that Adam shouldn't blame nature but should be guided by wisdom to love his wife but not be ruled by passion. The irony is, that that both Eve and and Wisdom are in the feminine - Raphael speaking of both in the feminine pronoun actually creates a bit of confusion in the reader's mind, requiring a second reading - yet Milton insists the woman is naturally, pre-fall, the inferior of the man in wisdom.

Angels enjoying "whatever pure in the body thou enjoyest" raises an eyebrow. We know Jesus said that angels neither marry nor are given in marriage (Matthew 22:30). I suppose it could be said that rules regarding intimate union on earth are different than rules in heaven, but I doubt it. To quote G. K. Chesterton, "Reason and justice grip the loneliest star... On plains of opal, under cliffs cut out of pearl, you would still find a notice-board, "'Thou shalt not steal.'" (from The Blue Cross).

I’m on the road speaking and can’t wait to catch up on these comments when I’m home!