"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”1

With Book 7 of Paradise Lost, we begin the second half of the epic.

Again, it helps to look at the overall structure.

Book 1, which opens the first half of the poem, is set in the fiery, consuming lakes of Hell where Satan and his followers face eternal punishment. Book 7, which opens the second half of the poem, is set in the lovely, generative new world made by God for humankind and all other creatures and created things, which he declares “good.” This “big picture” is helpful to keep in mind as we read.

Adding to this significant structural shift is a deep contrast between the mood and tone of each of these books. In literature, a tone or mood is created not by what is portrayed but by the words and imagery used to describe what is happening. The tone of Book 1 is, aptly, dark and foreboding, while the tone of Book 7 is light and joyful.

I went back to Book 1 to look at some of the words and images that Milton uses to describe this place called pandemonium. They include “chains,” “penal fire,” “horrid,” “vanquished,” “fiery,” “lasting pain torments,” “baleful,” “dismal,” “waste and wild,” “dungeon horrible,” “furnace flamed,” “darkness,” “doleful shades,” “fiery deluge,” and “ever-burning sulfur unconsumed.” And that’s all from just one short passage (48-69).

The contrast between the language used for this place and the language that describes the scene of creation in Book 7 could not be more dramatic.

Rather than the images of death, pain, and destruction that characterize the mood of Book 1, Book 7 uses language that conveys light, warmth, fruitfulness, and life. You could drop your pen on the page and it would hit such imagery every time, but a few exemplary words and phrases that leaped out at me include “capacious” (290), “generate,” “abundant,” “plenteously,” “fruitful,” “multiply,” “fill,” and “innumerable swarm” (387-99).

For me, it is the mood of Book 7 that leaves the most overwhelming impression.

Another strong impression comes from how closely Milton sticks to (while clearly expanding on) the biblical account of creation in Genesis in portraying Raphael’s narration of those events to Adam and Eve.

Milton includes all the key parts: God’s words declaring his creation “good,” the order of creation on the six days, his rest on the seventh. All of this is, of course, embedded within the larger narrative which is entirely of Milton’s literary imagination.

I want to look at some of my favorite parts and passages from Milton’s creation account.

First, beginning in line 224, Milton portrays God using a compass to circumscribe the universe. This is a quintessentially modern, scientific, and Enlightenment image, to be sure. Indeed, we saw this very image employed by John Donne in his metaphysical poem, “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning,” which we discussed here at The Priory some weeks back. Milton pictures God using one foot to center the compass while turning the other to create the vast bounds of the universe in a way that is “just,” or perfectly proportionate. Yet, even though such an image is very relevant to Milton’s own time, it is also one taken straight from scripture: Proverbs 8:27 says that when God established the heavens, he drew a circle on the face of the deep (ESV). The King James Version says he “set a compass upon the face of the depth.” I think if I had known about these passages, I’d have enjoyed high school geometry so much more!

In line 235, Milton echoes a line in Book 1 (17): “his brooding wings the Spirit of God outspread” as God initiates creation by infusing life and “vital warmth” throughout the mass of “watery calm,” before commanding, “Let there be light” (243).

A favorite (long) passage for me from this book is this one that describes the earth as an embryo in the womb of the waters, not yet appearing, and the mountains as emerging from the same:

The Earth was form'd, but in the Womb as yet

Of Waters, Embryon immature involv'd,

Appeer'd not: over all the face of Earth

Main Ocean flow'd, not idle, but with warme

Prolific humour soft'ning all her Globe,

Fermented the great Mother to conceave,

Satiate with genial moisture, when God said

Be gather'd now ye Waters under Heav'n

Into one place, and let dry Land appeer.

Immediately the Mountains huge appeer

Emergent, and thir broad bare backs upheave

Into the Clouds, thir tops ascend the Skie:

So high as heav'd the tumid Hills, so low

Down sunk a hollow bottom broad and deep,

Capacious bed of Waters: thither they

Hasted with glad precipitance, uprowld

As drops on dust conglobing from the drie;

Part rise in crystal Wall, or ridge direct,

For haste; such flight the great command impress'd

On the swift flouds: as Armies at the call

Of Trumpet (for of Armies thou hast heard)

Troop to thir Standard, so the watrie throng,

Wave rowling after Wave, where way they found,

If steep, with torrent rapture, if through Plaine,

Soft-ebbing; nor withstood them Rock or Hill,

But they, or under ground, or circuit wide

With Serpent errour wandring, found thir way,

And on the washie Oose deep Channels wore;

Easie, e're God had bid the ground be drie,

All but within those banks, where Rivers now

Stream, and perpetual draw thir humid traine.

The dry Land, Earth, and the great receptacle

Of congregated Waters he call'd Seas:

And saw that it was good … (276-309)

The word “conglobing” in line 292 to describe the way in which drops of water form little globes as they land upon dry ground is both enchanting and utterly realistic in minute detail. Simply picturing this within the context of God’s grand scene of creation makes me marvel at his vast power and his loving attentiveness. I think Milton imitates the Creator well in this regard.

One other favorite passage: This is where Milton depicts the beasts climbing out of the ground. This delights me to no end. First is a language thing. Remember Amelia Bedelia, the children’s book character, and how she misinterprets so many idioms by taking them literally? It’s been decades since I read that book but I seem to recall one description of her “putting the lights out” by taking them outside and stringing them up in the clothesline so that they are “out.” (Language is so fun!) Well, Genesis 2:19 says that God formed the animals “out of the ground.” Until I read Paradise Lost, I always read that as making the animals from the material of the ground. I didn’t picture God making the animals coming “out of” or emerging from the ground! But that is just how Milton depicts it. And it makes complete sense to me.

It is also how the Italian Renaissance painter Raphael portrays it, too, in his painting of creation which hangs in the Vatican (the painting posted above).

No wonder the angels at the start of Book 7 were so full of praises to the Creator! And, too, Adam and Eve at the close!

Next week’s post on Book 8 will be a guest post from an actual Milton scholar (which I am not). I cannot wait to treat you (and myself) to that!

***

We will read The Pilgrim’s Progress together in coming weeks! We’ll rest a bit after finishing Paradise Lost. But if you want to plan ahead, you might consider getting a good edition for yourself. As the second most published book in the world (after the Bible), there are many. One word of caution is that many of these are redacted, abridged, and modernized—so there are great variations. This is the old copy I use, from Oxford World Classics. I’d say you are safe with any unabridged edition with original marginalia (and editorial notes also help). Note that some editions are modernized and take various liberties in so doing.

***

BOOK NOTE:

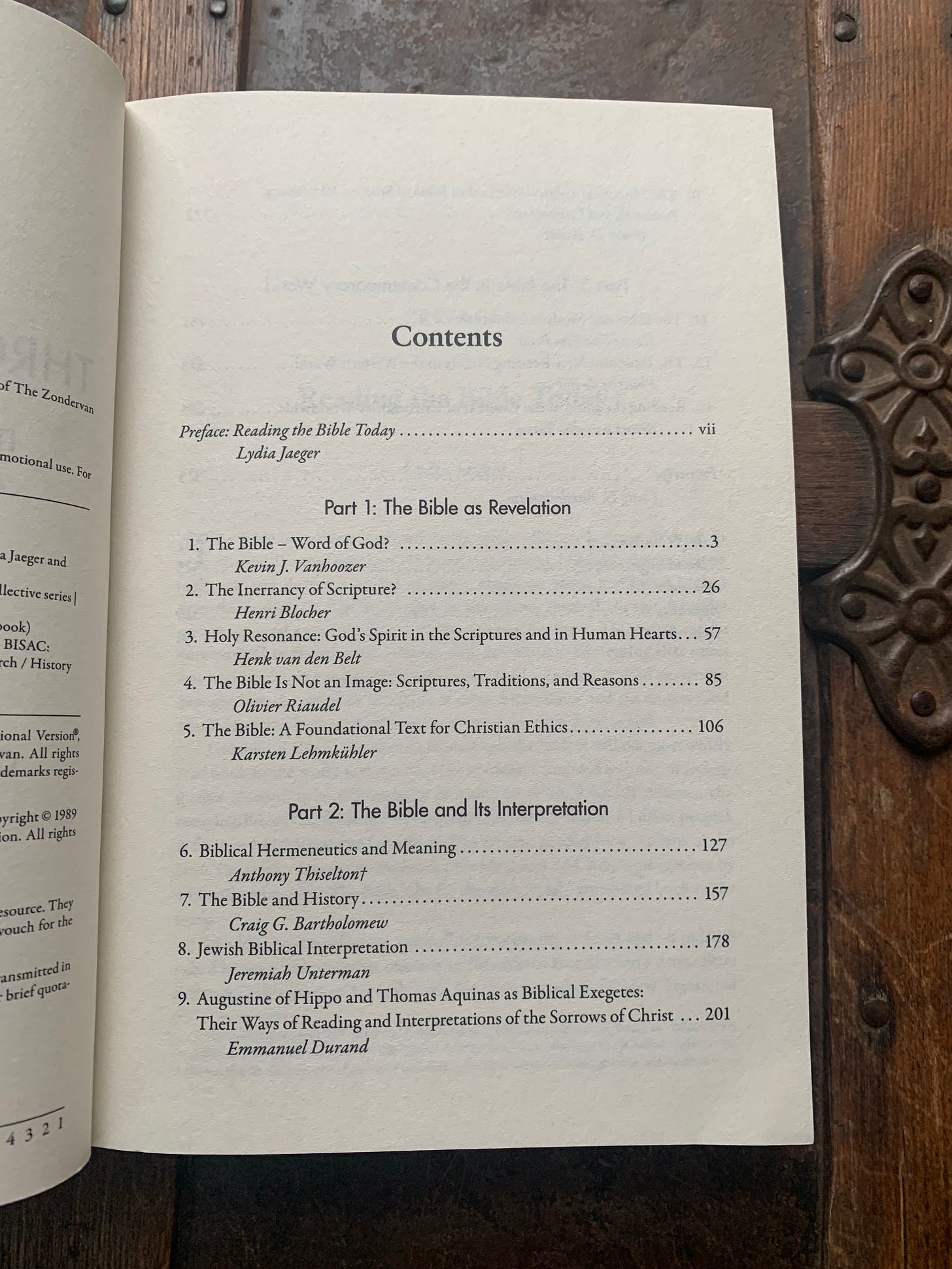

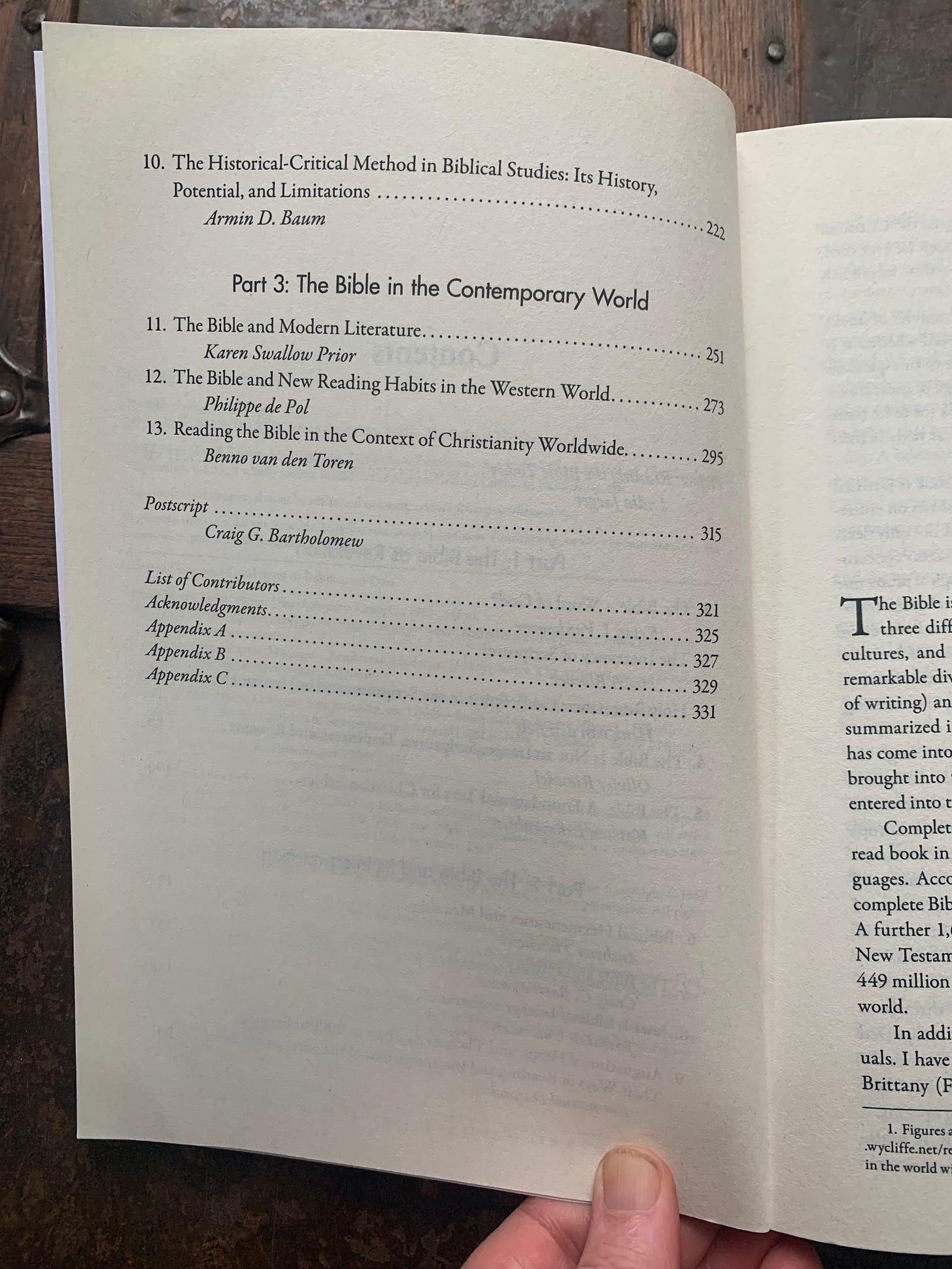

I finally have in my hands my copy of a book that has been in the works for some time, and to which I was honored to contribute a chapter. The book, The Bible Throughout the Ages: Its Nature, Interpretation, and Relevance for Today (Zondervan 2024) is an edited volume resulting from a collaboration of English- and French-speaking scholars writing on, well, just as the title suggests, how the Bible was read and understood throughout the ages. My chapter is on the Bible and modern literature. It really is a rich book!

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

I am so glad you mentioned the creation of the animals straight out of the earth. I laughed at the lion’s emergence:

“The tawny lion, pawing to get free

His hinder parts, then springs as broke from bonds,

And rampant shakes his brindled mane;”

That is so visual, and so exactly lion-ish!

For me, Book VII initially proved to be less provoking than previous Books. In short, I found the familiarity harder to overcome here. I think a large part of that is down to the slight change of approach. Until this point—for the most part, at least—Milton has drawn upon great swathes of Scripture, amalgamated them into his own narrative, added some imagery from classical literature for good measure, and then incorporated his own interpretation. In the first couple of pages of VII, he continues this trend, before turning to Genesis I and then simply* illustrated that narrative as he went. That change was necessary here, I think, but less stimulating.

All of that to say, I went away from this with two different takeaways, one negative, one positive. The negative in short was, I missed some stuff. In Books I-VI, I knew that I needed to be looking out for those extra layers, whereas here I could feel myself just moving with the motions of the movie playing out in my head. More than I few times I felt myself thinking, "I know this already." I saw certain allusions to other scriptures and stories, but those were washed away by the next wave of creation before I had much to think or say about them.

However.

By the end of VII—sitting with Adam at Raphael's feet—I began to feel the weight of that familiarity. "I know this" became, "Adam knew this!" and then, "If you know this, Adsum, do you live like it?"

God, having drawn the borders of the universe, took time to draw creatures out of the depths of our planet, us included! That should astound me, but I'm so used to it. Days can pass by without my thinking about it. If God created a lamb out of the nothingness next to me right now, I'd be beside myself, but the enormity of creation feels normal.

This morning, I have two questions to ask myself.

- How much have I missed?

- How much more will I miss, if I'm not careful?

Grace and Peace,

Adsum Try Ravenhill

*As simply as Milton was able...