As we approach Book 6, it is helpful to step back and take a big picture look at where we are in the epic.

Paradise Lost is comprised of twelve books. In reading through Book 6, we are at the halfway point! Whether that is relief or sadness to you, we need to consider structurally what has happened.

As I stated in my post about Book 1, Paradise Lost begins, as is traditional with classical epics, in medias res—in the middle of things. The work opens with Satan and his fellow fallen angels on the floor of Hell (“pandemonium”). The books that follow move forward in time and plot to Satan’s searching out the new world and its new creatures made in God’s image, Adam and Eve. Their fall into sin (the “after” that is yet to take place within the story) is foreshadowed by the dream Satan whispers into the ear of sleeping Eve. Then in Book 5, Raphael tells Adam about all that led up to Satan’s fall, filling in the “before” that occurred previous to the “middle” with which the entire work opened. Rather than being narrated in a straightforwardly linear fashion, the narrative goes from middle, to beginning, to end (and then, as we shall see, hints at the future that is far ahead).

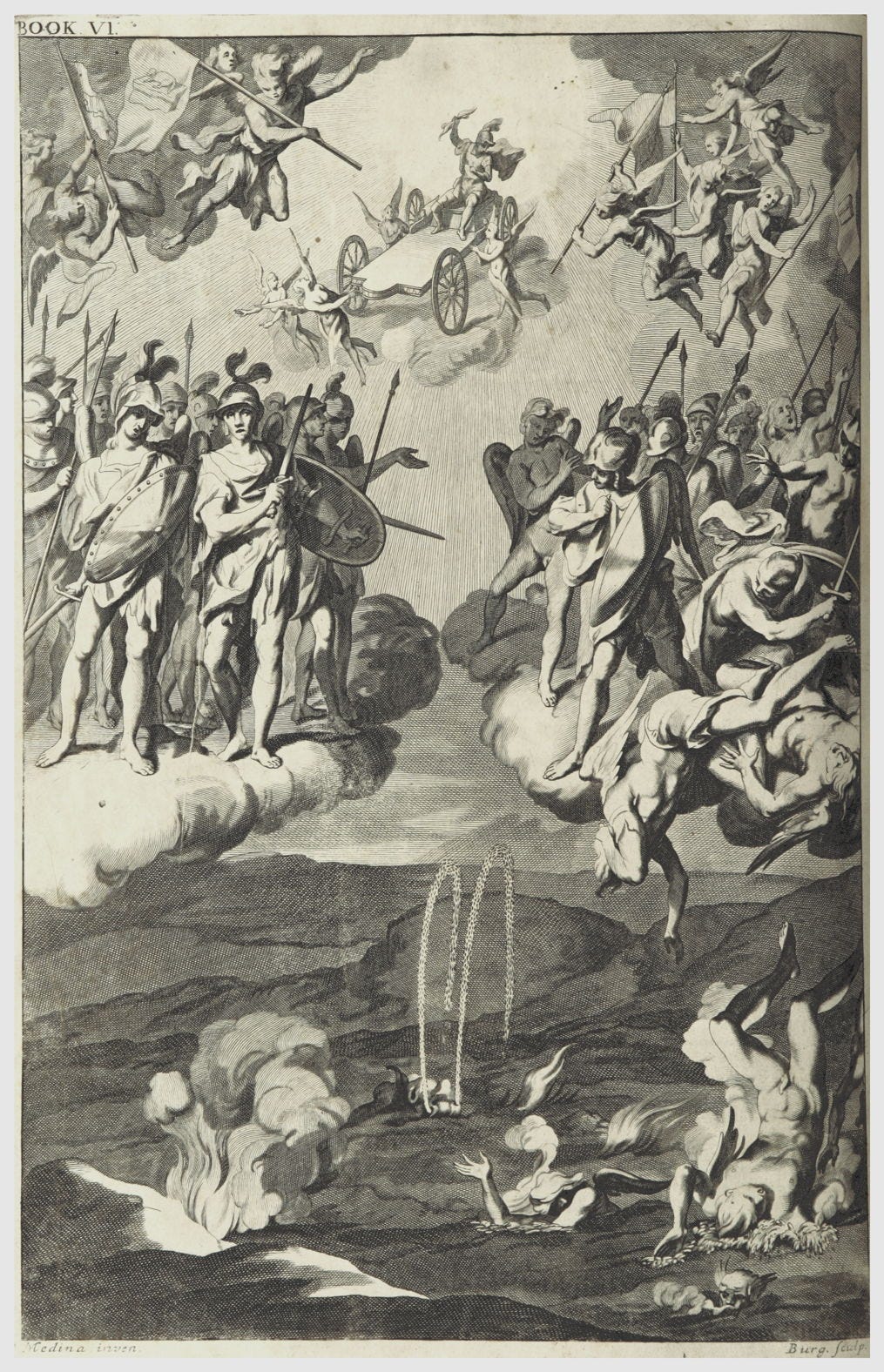

Book 6 continues what was begun in Book 5: Raphael is telling Adam about the great war in Heaven begun by Lucifer’s rebellion and ending in his being cast down to Hell. Raphael’s narration constitutes a story within the story. Indeed, about half of Book 5 is comprised of the start of this story within the story. Most of this concerns the seraph Abdiel, the sole angel among Lucifer’s legion of rebels who chooses to flee and return to God’s side.

Structurally, it is significant for Milton to spend this much time on this singular event. One thing it illustrates is that such a created being is free to choose whom he will serve, just as Adam and Eve are. Secondly, the context in which this story is told is Raphael’s coming to Eden at God’s behest in order to remind and warn Adam to remain obedient. Thus, the story of Abdiel presents a picture of a parallel temptation that Adam and Eve will face: serve and obey God or choose not to. (Technically, Abdiel’s story is a story within Raphael’s story within Milton’s story. Talk about a frame narrative!)

Book 6 ends where we began—with Satan and his rebels hurled down into the pit of Hell. We have come full circle. And then some. Book 6 ends with Christ’s victorious return to his Father in Heaven. The epic is now half told. Again, we already know the entire story (at least Milton could safely assume all his readers did).

So the question we should ask is what is the effect Milton achieves in structuring the story this way?

There are lots of answers to this question. One answer I think of is in terms of parallels: the first half of Paradise Lost features one rebellion and Christ’s victory over that rebellion. The second half will consist (spoiler alert!) of the same.

And yet it will not be exactly the same, will it? And that difference is surely among the truths Milton wants to convey. This is a question we might keep in mind as we continue reading.

Now, to look at Book 6 a bit more closely.

To be completely transparent, I must disclose that battles (and “action” scenes of any kind) bore me. I’m sure it’s the way my brain is wired. I just can’t follow action or sports or fast-paced sequences (or even slow-paced as might be the better description for the battle scenes of Paradise Lost, haha!). So I will do the best I can to pick up on some important things that do arise from this action-packed book.

Perhaps the most interesting is that Milton “credits” Satan with inventing the cannon, fueled by gunpowder, to use in his war against God’s army of angels. There is much in history and literary criticism written on this. I want to make just a couple of observations.

I’m no expert (and know little, in fact) in the history of warfare. But with each different kind of machine of war capable of doing more kinds of damage we can find writers and thinkers pointing out the decline in civil society sure to come with such developments. “War is hell,” as the saying goes, and the machinery of war can be rightly seen as of the devil’s party. For Milton the cannon and gunpowder were no different.

Milton was born just a few years after the infamous Gunpowder Plot of November 5, 1605, a foiled conspiracy by Roman Catholic interests in England to assassinate King James I by blowing up Parliament and thereby (they hoped) gaining a more Catholic-friendly monarch as a result. As I said, the plot was foiled. We already know how much Milton detested Roman Catholicism (for both political and religious reasons). Such a tumultuous event so recent in his country’s history certainly shaped him. When he was seventeen years old and a student at Cambridge, Milton wrote a poem in Latin, In Quintum Novembris (“On the Fifth of November”) on this event. (You can read an introduction and translation here.)

This poem, which depicts Satan as the engineer of the Gunpowder Plot, is clearly an early version by the young poet of what he would write in maturity in Paradise Lost. (In his introduction to the poem in the Riverside edition, Roy Flannagan describes it as a “miniature Latin epic.”) As I was reading it and saw the lines in which Satan refers to his followers as “the faithful” and the pope as “sovereign,” I noticed just how much Milton’s Satan (here and even more in Paradise Lost, of course) must have inspired Lewis in writing The Screwtape Letters. (In the Upside Down,1 what Satan calls good is evil, and vice-versa.)

This obscure early poem of Milton is even credited with inspiring (at least in part) the nursery rhyme commemorating Guy Fawkes Night (Fawkes was one of the conspirators, ultimately imprisoned, tortured, and hanged on the gallows):

Remember, remember, the 5th of November,

Gunpowder, treason and plot.

I see no reason

Why gunpowder treason

Should ever be forgot.

Guy Fawkes, Guy Fawkes, 'twas his intent

To blow up the King and the Parliament

Three score barrels of powder below

Poor old England to overthrow

By God's providence he was catch'd

With a dark lantern and burning match

Holler, boys, holler, boys, let the bells ring

Holler, boys, holler, boys

God save the King!

All of this to say, that Milton had personal, political, religious, and cultural reasons to link cannon warfare (and the gunpowder that fueled it) with Satan. It’s also noteworthy that Satan “invents” but does not create. In Book 6, he looks at the materials God created and perverts them to evil purpose (469-98)—as he always does.

Of course, this leads to another aspect of Book 6, and that is the very idea of warfare between angels, who (as many critics point out) can’t die except at God’s will. Their swords and cannons impede them momentarily in their battling but do no mortal harm.

It’s such an odd thing to picture that Alexander Pope ends up parodying it a few decades later in his mock-epic poem, The Rape of the Lock (1712)—a brilliant work that I won’t get into now. (But maybe we will read it together in the future? I adore Alexander Pope, but he’s a hard sell these days.)

On one level, it’s as inconsequential as (pardon my crudity, but it seems apt) a pissing contest,2 with no more at stake than false pride. In fact, the Riverside edition notes that “the cannons are phallic in shape but impotent” (p. 522, note 147). (We have so many such battles these days, don’t we?)

At the same time, if the angels are just battling one another in a war in which their own physical actions have no real, lasting consequences then what’s the point?

Ah. Perhaps we could ask ourselves the same question. The point for them is the same as it is for us when we know how things will end, and who the victor is. The point is our own obedience, our own service to our sovereign (whichever one he might be), and our glorification of him.

Christ wins. Now, then, in the future, and in Paradise Lost. And, of course, he did so, as described in Book 6, on the third day.

And once again, I’ve barely scratched the surface here. I am trying throughout this series to balance text and context. The balance this week tilted toward context, and in covering so much background and history, I’ve paid less attention than usual to the actual poetry. But you, readers, never fail here. Post your memorable lines, phrases, passages, questions, and insights in the comments!

In two weeks, we will discuss Book 7. Next week, I am excited to be able to feature a guest post on the revolutionary nature of Milton’s angels. It will be an interlude of sorts as we approach the second half of this magnificent epic work.

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”3

***

BOOK NOTE:

John Hawthorne has been a friend for many years now. I’ve admired his work and enjoyed his support, and I share his excitement at the release this week (February 13) of his newest book, which has been a labor of love for some time now. The title, The Fearless Christian University, says it all. What a need for our day. Congrats, John! I think John Milton would approve your effort.

Alexander Pope has a whole one of these contests in another of his witty satires, The Dunciad, published in 1728.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

I have read vv 498-506 over and over. Raphael continues the narrative describing the personal disappointment of individual fallen angels that they hadn't a role in the development of gunpowder and then imagines that one might "devise like instrument to plague the sons of men for sin, on war and mutual slaughter bent." In the ears of Adam and Eve a nightmare unimaginable, But for us, evidence of the perversion that we've suffered and suffer on others. Lord, have mercy.

Its funny you mention what you do about gunpowder. Milton wasn't alone. In Luther's Table Talk, the reformer muses about the origins of firearms.

No. 3552: Modern Instruments of War Deplored

March 19, 1537

Afterward he [Martin Luther] spoke of firearms and cannons, those most inhuman devices which smash walls and rocks and slay men in battle. “I think these things were invented by Satan himself, for they can’t be defended against with [ordinary] weapons and fists. All human strength vanishes when confronted with firearms. A man is dead before he sees what’s coming. If Adam had seen such devices as his descendants have constructed to fight one another, he would have died of grief.”