I reserve the right to change my mind, but Book 4 might be my favorite book of Paradise Lost. (I hope I don’t lose any of you here! The rest of the poem is amazing as well!)

We go in the first three books from the darkness of hell and chaos to the bright glory of Heaven. And in Book 4 we land on Earth. In this book we see good and evil mixed: Satan prowls, the garden teems with glorious animals and verdant vegetation, and two noble creatures walk upright with the stamp of God’s image in their bearing. Even before the fall is depicted in the poem, this is the world we know even though ours is the fallen one.

Milton gives extended descriptions of the beauty and glory of creation here. Of particular note is the beautiful detail offered in lines 223-84 of the river running through Eden (which is mentioned in the Bible in Genesis 2:10). Unless I missed a period, the entire sentence containing these lines doesn’t even end until some more lines later. This passage, like a river, gently winds around and through and around again. The footnote in my Riverside edition observes that there were no thunderstorms in the Garden of Eden; rather the garden has “a perpetual source of gentle watering” from this river.

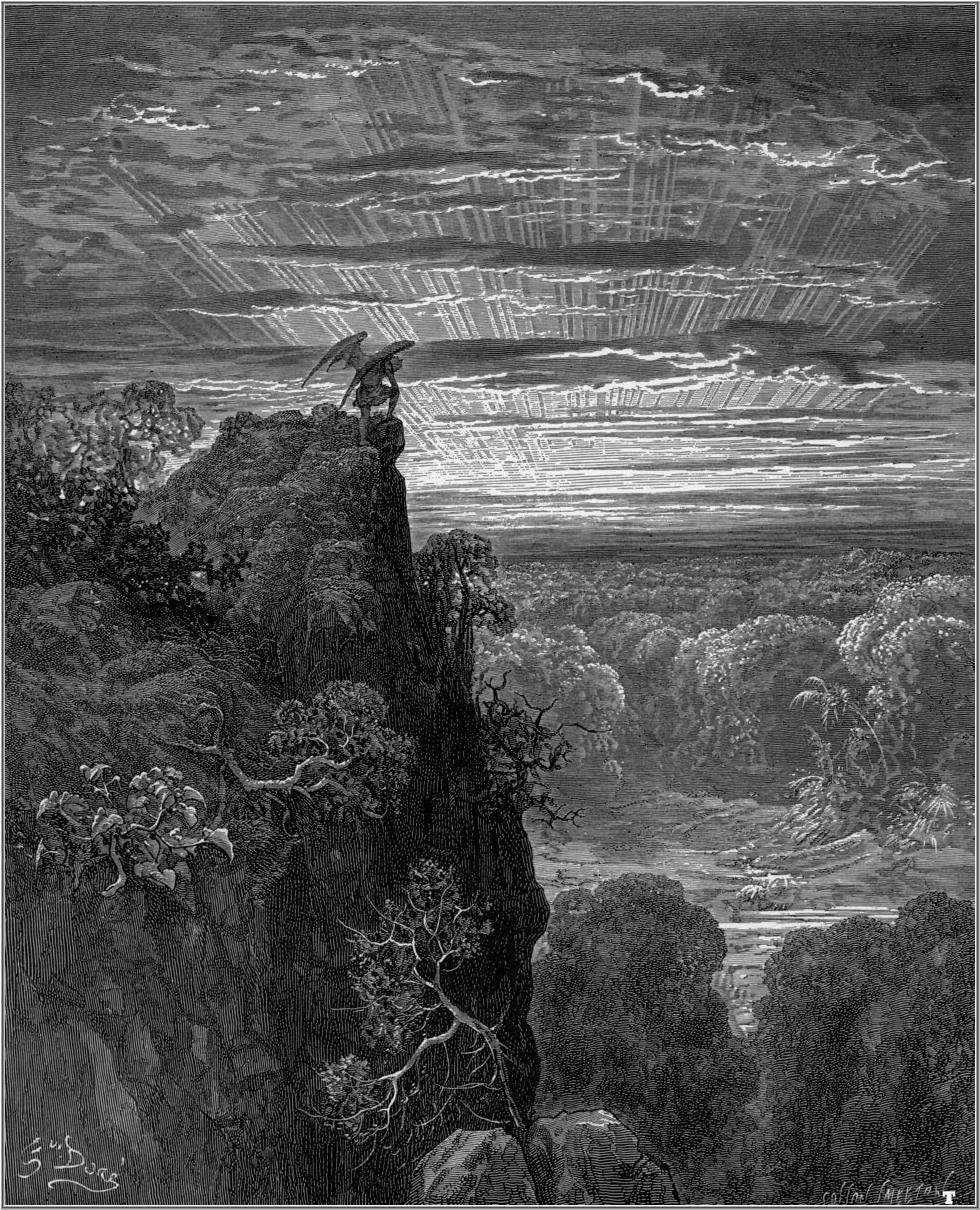

This “sentence” ends by bringing us back to the “Fiend” in line 285 who has been surveying all this, but, the poem says, “saw undelighted all delight” (286). What a powerful and poignant description of the Evil One. He can see so much beauty and goodness before him and yet cannot (or does not) delight in it. (I cannot help but examine myself and ask if I am ever guilty of the same. This phrase is very convicting.)

There are other punchy, powerful descriptions of Satan in this book which reveal deep spiritual and psychological insights into the nature of evil.

Satan curses God’s love, “since love or hate, / to me alike, it [God’s love] deals eternal woe” (lines 69-70)

He then curses himself, saying,

… since against his thy will

Chose freely what it now so justly rues.

Me miserable! which way shall I fly

Infinite wrath, and infinite despair?

Which way I fly is Hell; myself am Hell … (71-75)

Satan goes on to consider (or at least pretend to consider) repentance, but tells himself (or rationalizes) that repentance cannot “unsay what feigned submission swore” and “never can true reconcilement grow / where wounds of deadly hate have pierced so deep” (93-99):

So farewell, hope; and with hope farewell, fear;

Farewell, remorse! all good to me is lost;

Evil, be thou my good … (108-10)

In addition to the inner psyche of Satan, Milton provides stunning visual portrayals throughout the book of Satan’s wiles. I find the description of Satan flying to the top of the Tree of Life where he sits like a cormorant (lines 172-201) utterly terrifying. (Perhaps I’ve watched Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds too many times?) When I did a search of cormorant, the first thing that popped up was this video, the title of which calls it “the world’s most hated and reviled bird.” Yikes.

Then, of course, we see Satan compared to a hungry, prowling wolf (183), a thief (188), and a hireling in the church (193). Milton was outspoken about the many corrupt clergy of his day, particularly the practice of hiring out the “livings” (as some clerical appointments were called) within the Church of England. He believed clergymen should be tentmakers, earning a living from other work, according to Roy Flannagan in the Riverside edition. So for Milton, a “hireling” like that mentioned in John 10:12 was a nasty thing indeed.

But this Book isn’t all Satan. No, indeed. Here we are introduced (first through Satan’s eyes) to Adam and Eve, portrayed, as best as Milton can, in their unfallen state--“sufficient to have stood, though free to fall,” God explained in Book 3 (3.99). Being fallen, can any of us really imagine what that condition would be like?

So how does Milton portray our first parents? There are some things in that portrayal to admire, some to ponder, and some to question, I think.

The most overwhelming sense for readers today (at least speaking for myself) is the vehemence with which Milton expresses that Adam is superior to Eve in every way. They are “not equal” (496). Adam was made for “contemplation” and “valor” (497) and she for “softness” and “sweet attractive grace” (498). And later when Eve recounts waking from her first sleep upon being created she says that her beauty “is excelled by manly grace / And wisdom, which alone is truly fair” (490-91). So, clearly, in Milton’s rendering, Adam and Eve’s virtues are not merely different, but Adam’s particular excellences are superior to Eve’s. This is similar to the view that today’s complementarians deny and partriarchalists enthusiastically embrace.

Their retirement to their nuptial bower and its bed suggests a pure, unfallen sexual encounter. Yet Milton presents their unfallen union negatively nonetheless when he says that Eve did not refuse there the mysterious rites of “connubial love” (742-43). (Presenting unfallen sex as the woman not saying “no” is not exactly ideal. While we do not know the reason why, Milton’s newlywed wife did desert him shortly into their marriage, only to return eventually. And Milton did argue in favor of divorce, which was quite controversial at the time.)

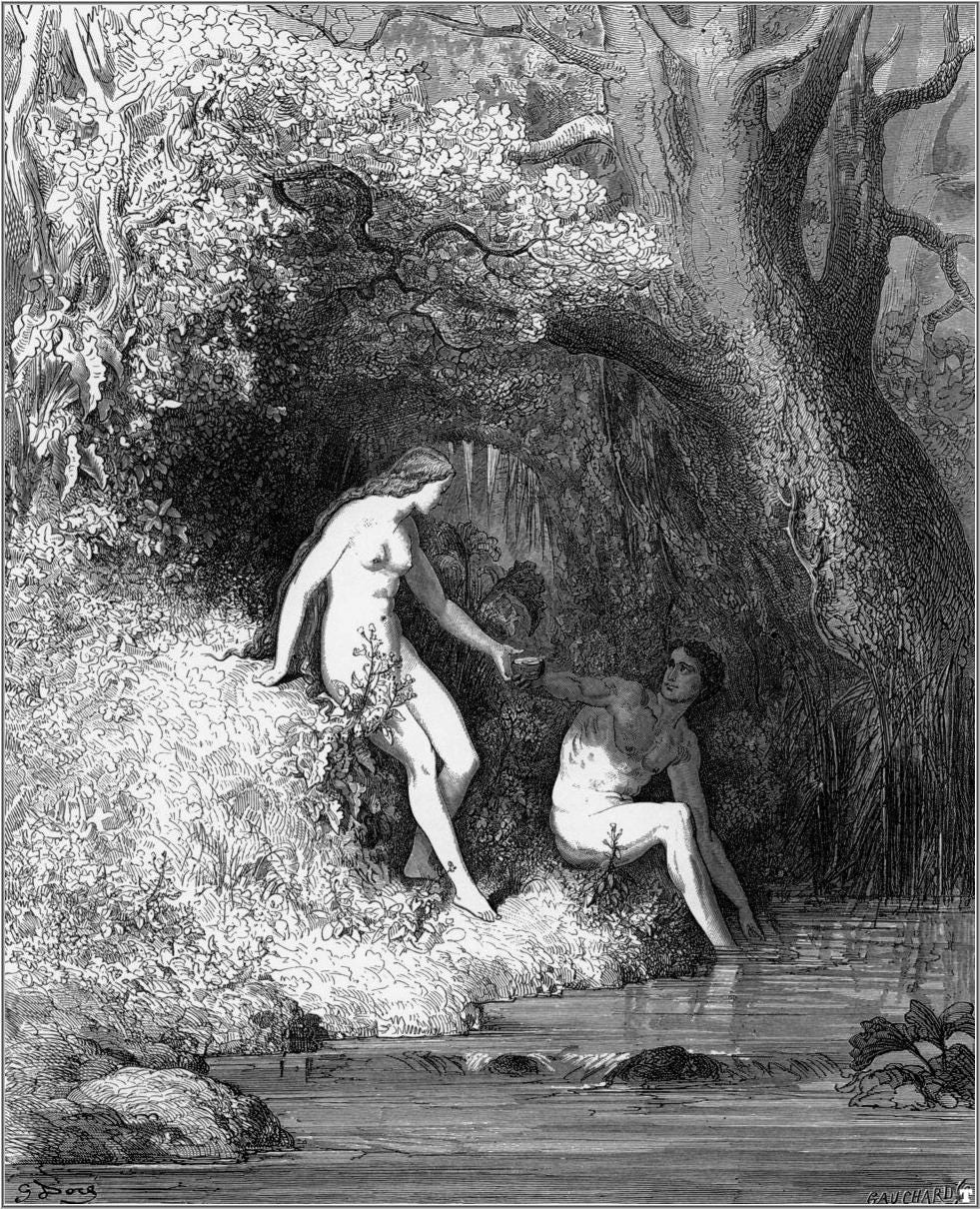

I do love how Milton describes the pair reclined on the riverbank, eating fruit and drinking water from a cup made from the rind, while all the beasts of the earth skip and play around them (320-55).

But Satan is there in that scene, too. He is always there in this book. Watching. Preying. Scheming. Milton even shows him as a voyeur as the two embrace in their conjugal union: he turns aside with envy, yet “with jealous leer” eyes them askance (502-04). In self-imposed agony, he exclaims:

Sight hateful, sight tormenting! thus these two,

Imparadised in one another’s arms,

The happier Eden, shall enjoy their fill

Of bliss on bliss; while I to Hell am thrust,

Where neither joy nor love, but fierce desire,

Among our other torments not the least,

Still unfulfilled with pain of longing pines … (505-11)

The way Milton ping pongs back and forth between Eden and Satan, between Paradise and Hell, between the heavenly angels and the fallen angel in this book captures so well this fallen world.

In presenting a yet-sinless world, Milton has Satan, taking the form of a toad, first speak to Eve in a dream. This seems to serve to prepare the ground for the temptation to come (797-822). I’m not sure this was a move that was theologically or imaginatively necessary, but it is interesting.

Another artistic touch that impressed me on this reading is the notion of shame—both its presence and its absence—throughout this book. In first describing Adam and Eve, the poem notes that they do not yet conceal the “mysterious parts” of their bodies because they have yet to feel guilt or shame (312-13). But more interesting than this mention of shame (or its lack) is an earlier passage, one I referred to earlier where Satan considers repentance, but chooses not to. Here he says,

…. Is there no place

Left for repentance, none for pardon left?

None left but by submission; and that word

Disdain forbids me, and my dread of shame

Among the Spirits beneath, whom I seduced

With other promises and other vaunts

Than to submit, boasting I could subdue

The Omnipotent. Ay me! they little know

How dearly I abide that boast so vain,

Under what torments inwardly I groan,

While they adore me on the throne of Hell. (79-86)

Satan’s “dread of shame” –- the shame he would feel from his friends, the one he seduced into rebelling with him, if he were to change his mind –- is enough to keep him from repenting.

And this is what shame does. Brene Brown famously says this about shame: “Shame corrodes the very part of us that believes we are capable of change.” Satan uses shame to keep us from repentance and reconciliation from God, doesn’t he?

Sin came into the world when Adam and Eve sinned. But Milton shows that shame was here long before because Satan was here, Satan who is always whispering in our ear, always inviting us to feel his shame.

But Satan isn’t the only angel in these here parts. God has given us Gabriel, Uriel, and all the heavenly host.

Next up: Book 5

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”1

***

BOOK NOTE:

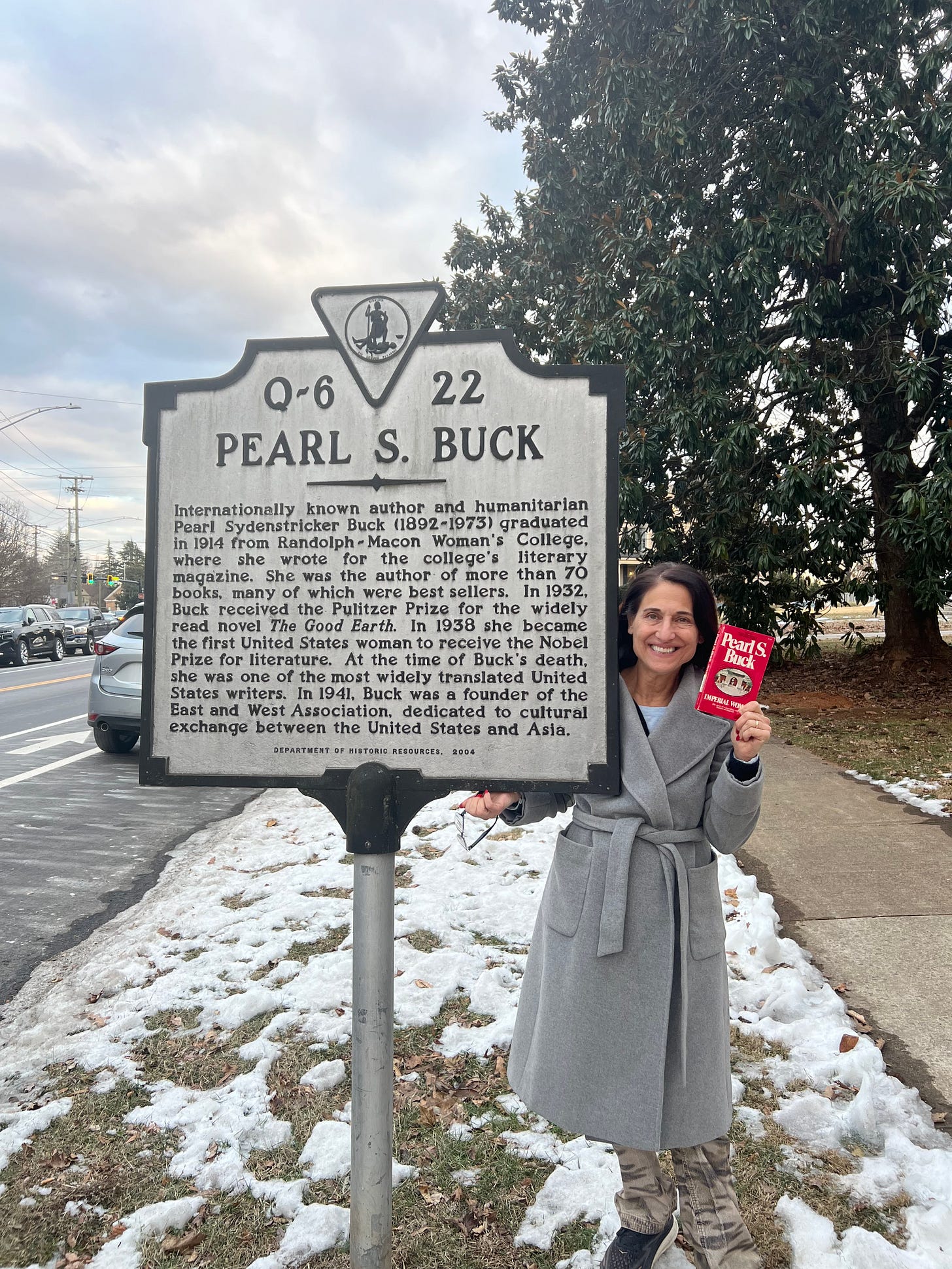

My friend

(who proofreads these posts for me so faithfully and well) gave me this book recently: Simple Abundance: A Daybook of Comfort and Joy.The entry for January 16 has this quote from Pearl S. Buck: “Order is the shape upon which beauty depends.” This is an apt quote to describe Milton’s poem, of course. But I have another reason for mentioning it. I had a visit last week from a very dear, old friend. She rarely reads fiction for pleasure and decided to bring a book along on her trip to enjoy. It happened to be one by Pearl Buck. But here’s the crazy part: my friend had no idea that Buck has a connection to where I live. Buck, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature for The Good Earth in 1938, graduated from a local college, then Randolph-Macon Women’s College. I took my friend on a hunt for the historical marker while she was here and what fun it was to find!

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

I'll be honest, I found Milton annoying in this chapter. It isn't just how he depicts Eve, it is also other little things, like why does he have Gabriel, who is always a messenger in the Bible, be a sentinel and captain? Shouldn't it be Michael disputing with Satan? And what in the world is Pan doing in Paradise?! Yes, I know, Milton is a man of his time, where intellectuals spoke of nature and Pan interchangeably. But Milton places other pagan deities in Hell, i.e. Moloch, Baalzebub (Baal), Dagon. Why does Pan get off? Doesn't Milton know the origin of the word panic, which originally meant 'an unreasoning fear induced by the god Pan'? I saw a few ancient Greek depictions of Pan when I was in Athens and I turned away from them with a shudder - there was a sense of evil in those marble Pans that I didn't sense in other depictions of Greek deities.

But the biggest disappointment was during the evening scene. Milton's Adam and Eve don't walk with God in the cool of the evening. I wonder if his theology got in his way? He probably couldn't think how to depict the Father walking with them, but an orthodox theology would have them walking with the Son.

I also loved Book IV! Two observations that stayed with me:

1) Satan’s lostness and despair is so intricately portrayed that instead of the vile and scary portrait of him in previous books, I was overwhelmed by the regret and “eating away at oneself” that will never end— a loneliness and lostness that not only never improves, it never stops. It only worsens. It made me think of C.S.Lewis’s depiction of hell in The Great Divorce— utterly alone (instead of the “we’ll be miserable together” idea) and forever growing lonelier.

The self-destruction, regret, and despair in lines 18-25 in particular:

“Upon himself; horror and doubt distract

His troubled thoughts, and from the bottom stir

The Hell within him, for within him Hell

He brings, and round about him, nor from hell

One step no more than from himself can fly

By change of place: now conscience wakes despair

That slumbered, wakes the bitter memory

Of what he was, what is, and what must be

Worse; of worse deeds worse suffering must ensue.” (Italics mine)

2) In contrast with Satan’s realizations, the observation of Adam and Eve in the garden is wholly appealing and delightful. I wondered before reading it if there would be troubling, bothersome depictions of men and women because of Puritanism and Patriarchy and Bad History. And there were a few lines that sounded off of course. But I didn’t get the same warning signs of a denigrating view of women as some did. Is it possible to have a more charitable reading? Or am I woefully unable to see the problem? I don’t fall into either of the complementarian/egalitarian camps but would probably lean more egalitarian if pushed on an interpretation of these things from a unified biblical persepctive. Still, the picture of Adam and Eve in the Garden here, to me, read more as a fully satisfying and utterly untarnished fellowship with one another that possibly reflects the original intention and creation of a man and woman, without the mess that has ensued from the fall. Even the parts that can sound abrasive in our current moment (e.g. “Whence true authority in men; though both/ Not equal, as their sex not equal seemed/ For contemplation he and valour formed/ For softness she and sweet attractive grace/ He for God only, she for God in him:” (295-299), I read as an affirming of the beauty of gender creation, and what we could even read as missing when we don’t affirm binary sexes. It’s striking that Satan is utterly enthralled by their worthy, divine, image-bearing glory (not disgusted). And the sweetness of their mutual satisfaction and enjoyment of one another is something he will never experience.

Several lines also pointed to a joint companionship in work and play and worship (lines 610-619 where Adam calls her his “Fair consort” in their mutual need of rest from their daily work appointed by God, and in 726-28 where he says, “Which we in our appointed work employed/ Have finished happy in our mutual help/ And mutual love, the crown of all our bliss” 726-728). The picture is of working alongside one another in the garden. But there is certainly a descriptive difference in the qualities of their attraction to one another. And I guess this too I found more affirming than prescriptive. Maybe Milton describes her submission to Adam in their foreplay (is he actually talking about foreplay? It seems like it!) And that is off-putting. But it might also be actually just feminine. And it might not mean that everything a woman does has to be submissive, but that pre-fall it was pretty great. And Adam didn’t exploit it or turn away from it. He gave her what she wanted and needed. (740-744) It was mutual. The best display of the mutuality everyone seems to be hankering so hard for today. (Karen, I know you read line 743 where Eve does not refuse Adam differently. So maybe I am misinterpreting here.)

Finally, it seemed to me as if Milton was going on and on in an effort to say that the beauty of their sexuality and sexual intimacy is absolutely celebrated and reflective of the image-bearing quality of true relationship and love— which again is something that is so starkly different from the loneliness of the separation from God and from all fellowship of any kind we see in Satan. I know that Milton was a Puritan, but whatever forms of prudery people often associate with puritanism (or an Augustinian view of sex), this seems to be flying in the face of all that (Lines 745 and on—).