In closing last week’s post, I suggested that as we read more of Paradise Lost, we think more about the overall structure of the work and the effect achieved by that structure. That’s where I want to begin our discussion of Book 3.

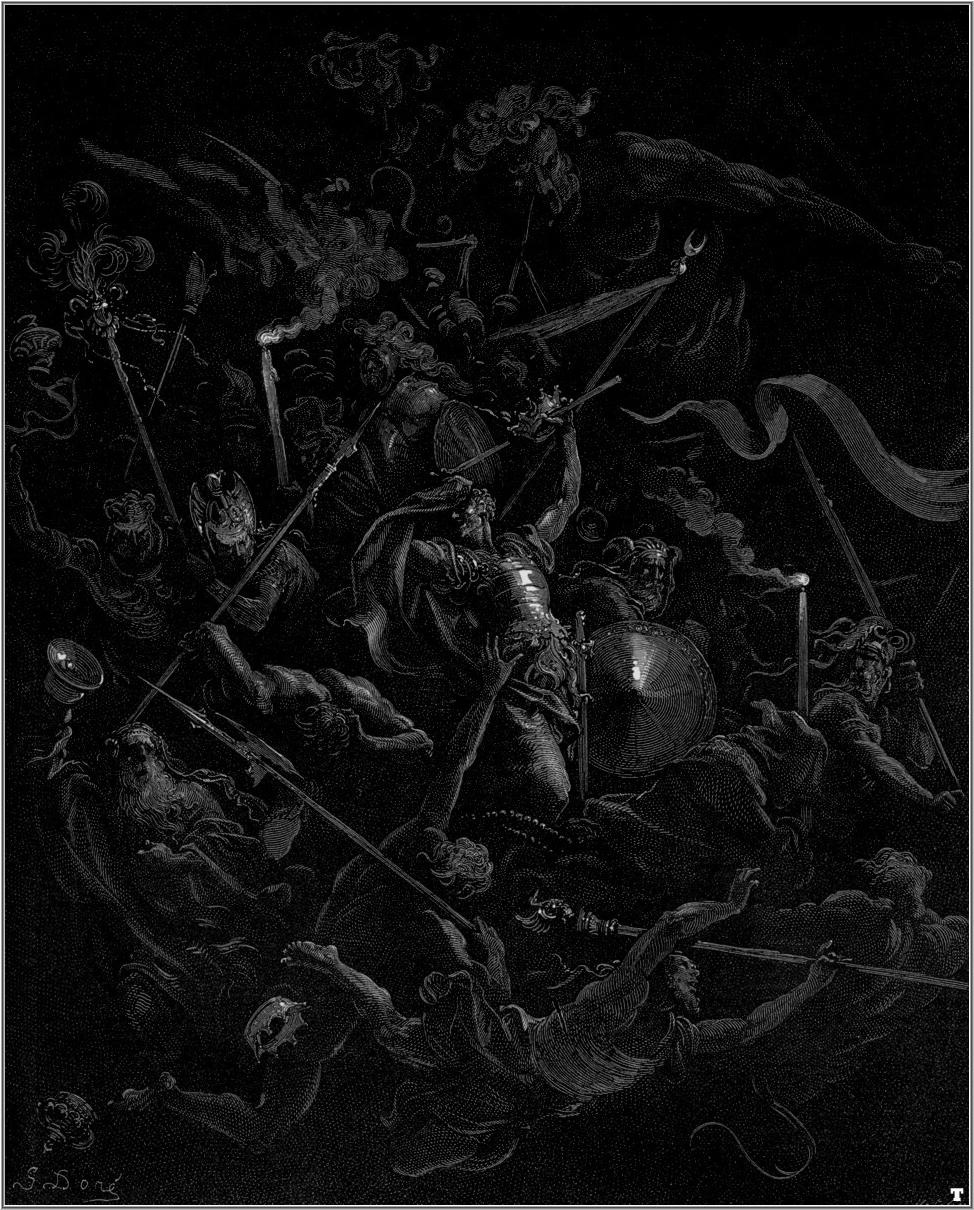

In leaving Books 1 and 2, we are emerging from a couple thousand lines describing a world of sin, death, and eternal night. The imagery of darkness as Satan flies “over the dark abyss” (2.1027) is overwhelming. But as he does so in those final lines of Book 2, something else emerges before the book closes, and Chaos begins to “retire” (2.1039):

… at last the sacred influence

Of light appears, and from the walls of Heav'n

Shoots far into the bosom of dim Night

A glimmering dawn … (2.1034-37)

Then, suddenly, Book 3 opens in a suffusion of light, “holy Light,” “eternal coeternal beam,” “bright effluence of bright essence increate” (3.1, 2, 6). What Milton has re-created is a sense of ongoing, interminable, and eternal chaos suddenly being broken when the Creator says, “Let there be light” (Genesis 1:1). In Book 3, set in Heaven, where God reigns with his Son seated beside him, we are in a world of light, love, and grace.

Here we see God bending “down his eye” (58) to view his creation, the making of which is retold in language that echoes the account given in Genesis:

… before the Sun,

Before the Heavens thou wert, and at the voice

Of God, as with a Mantle didst invest

The rising world of waters dark and deep,

Won from the void and formless infinite. (8-12)

Not all of Milton’s language—or concepts—are so closely rooted in Scripture. This book in particular is deeply theological. Some of that theology is good, and some of it is off (as is well-established in the literary criticism). I will touch on some of those key theological points (because it is impossible to do Book 3 justice without doing so), but I also want to explain why I will merely touch on them here and elsewhere.

Theology is important, of course, regardless of one’s religion. And for those who share Milton’s Christian religion, his theology is even more important. But we don’t read this poem for its theology—at least not primarily. We should look for it, be aware of it, and be discerning, of course.

But you know how every year at Christmas the “Mary, Did You Know?” debate comes up? (If you don’t, you’re lucky.) Every year, Christians like to debate the theological (I guess?) question about the popular contemporary Christian song that basically asks if Mary knew what the Christ child she was carrying would do. I honestly don’t even know what answers people give. She knew something was up considering the circumstances, but she certainly wasn’t omniscient. But here’s the thing: I don’t know the song that well and detest that style of music, but I am pretty sure it’s a rhetorical question. Doesn’t anyone remember rhetorical questions? (That was a rhetorical question, by the way.)

I bring all this up because regardless of Milton’s quasi-Arianism in his portrayal of the Trinity,1 I think ultimately what he is doing in Book 3 when he describes a conversation between God the Father and God the Son (in which the Son seems not to know quite what the Father is up to in his plan to save humankind) is a rhetorical situation more than anything else. As with the Mary song, it offers up interesting questions to ponder and even debate, but that’s not the primary purpose of reading the poem—or any poem (including a CCM song about Mary).

Much has been written about the nuances of Milton’s actual doctrinal views and how much they do or do not appear in this work (and others). That’s an interesting and important discussion on its own but not one that I can tackle here. I do think we can consider the strengths and limits of the dramatic sense achieved when a great poet attempts to portray what, in the end, cannot be entirely translated into words, what is (to invoke a Miltonic word), ineffable.

Why do we read poetry in the first place? For the aesthetic experience.

So let me point out a few of these important theological points—I emphasize few because there are so many here—and then invite you into the aesthetic experience.

Line 78 points out that God sees past, present, and future all at once. When he is looking down at creation and humankind, he sees and describes all outside of time. Christ affirms this with a few simple words when in 227 he says to God that “thy word is past.” This means that if God speaks it (even in the “present”), it is already done. Those four words are so powerful and theologically rich.

In lines 114-119, God makes the important point that neither predestination nor his own foreknowledge negate the free will he gave to humankind (not to mention the other spiritual creatures he mentions a few lines earlier). Of course, this entire relationship between God’s sovereignty and humanity’s free will is an issue that both divides denominations and remains, ultimately, a mystery. I don’t think Milton aims to solve the mystery, but he acknowledges it.

Even more than acknowledging this mysterious relationship between sovereignty and free will, Milton has God make clear that he made humankind

… just and right,

Sufficient to have stood, though free to fall. (98-99)

This is a key passage in Book 3. In fact, some critics say that humanity’s free will is the central theme of Book 3.

I think an even more prominent theological theme in Book 3 centers on God’s justice and mercy—and how his grace overcomes. This emphasis is seen in these lines, for example:

… man shall find grace And shall grace not find means, that finds her way,

The speediest of thy winged messengers,

To visit all thy creatures … (227-30)

Heav'nly love shall outdo Hellish hate (298)

… with the multitude of my redeemd

Shall enter Heaven long absent, and return,

Father, to see thy face, wherein no cloud

Of anger shall remain, but peace assur'd,

And reconcilement; wrauth shall be no more

Thenceforth, but in thy presence Joy entire. (260-65)

I could go on and on with lines like these about God’s mercy, love, and grace as described in this book. The heavenly host—the angels—are in some ways foils in these scenes: their silence, awe, and later their loud shouts and hosannas help us see, hear, and feel the goodness and might of God (see especially lines 344-364).

And here is my segue to what I really wanted to emphasize this week: the aesthetic experience of reading poetry. Now, as far as poetry goes, Paradise Lost is a lot, as is already clear. We have the allusions. We have the archaic and obsolete words. We have the Miltonic similes that go on for line after line. Although he greatly admired Paradise Lost, the great eighteenth century critic Samuel Johnson did admit that it is “one of the books the reader admires and puts down, and forgets to take up again. None ever wished it longer than it is.”

So let us at least feel the poetry where we can. Satan is described as a vulture that gorges on “the flesh of lambs” (434) as he walks “up and down alone bent on his prey, alone,” “on this windy sea of land” (440-42).

In contrast, Milton invites us our senses to “taste and see that the Lord is good” (Psalm 34:8):

Thus while God spake, ambrosial fragrance fill'd

All Heav'n, and in the blessed Spirits elect

Sense of new joy ineffable diffus'd:

Beyond compare the Son of God was seen

Most glorious, in him all his Father shon

Substantially express'd, and in his face

Divine compassion visibly appeared,

Love without end, and without measure Grace … (135-42)

What theological insights do you see in this Book? What errors? What aesthetic riches do you see, hear, feel in Milton’s poetry? What interesting words, arresting passages, new insights, surprises do you find? Please comment below!

Next week: Book 4. Read it online here.

BOOK NOTE:

This new edition of Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey from Renewed Books has a cover and introduction designed to attract young adult and teen readers—which is perfect, because this novel is Austen’s most fun! It’s for all ages, but it is perhaps the novel that would appeal most to younger readers. I’m delighted to see this new edition, especially since the introduction was written by one of my former students!

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”2

Arianism was a heretical teaching of the fourth century churchman Arius that held that Jesus was created by God and therefore not an eternal part of the Trinity. Orthodox Trinitarian belief is expressed in the Athanasian Creed.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

At the close of Book 3 there is a conversation between Satan and the Archangel, Uriel. With compliments and cunning, Satan coaxes the angel to tell him the location of man among all the stars and planets. (660) I find Milton's description of the give-and-take of this conversation in lines 680-690 to be very enlightening. "So spake the false dissembler unperceived; For neither man nor angel can discern Hypocrisy, the only evil that walks invisible, Except to God alone, by his permissive will, through heaven and earth: And oft though wisdom wake, suspicion sleeps at wisdom's gate, and to simplicity Resigns her charge, while goodness thinks no ill where no ill seems..." Hypocrisy can beguile even angels, apparently, and only God can see through hypocrisy's invisibility cloak. A very relevant warning.

Having received my copy a week late, it took until now to catch up! In order to do so, I had to make a commitment to stop underlining every passage along the way. Once I crossed that hurdle, I then had to constrain myself to reading only one short passage aloud per page, rather than the entirety of the book. I feel like a child again, picking up Shakespeare's plays for the first time.

With that said, it is Milton's use of silence that most affected me.

Man cannot save himself, but can lose himself. Once-heavenly beings can lead him to the path of damnation, and escort him down it, but they cannot—and will not—turn him away from it. The souls of the Elect (184) require one perfect redeemer, who can dwell among them, live a life contrary to theirs and yet beset by all of its temptations and trials, and then die in their place.

God seeks such a one:

"He asked, but all the Heavenly Choir stood mute,

and silence was in Heaven; on man's behalf

Patron or intercessor none appeared."

— III. 217-219

Milton's poetic license covers a very different vehicle here than a clergyman's license ever could, and so he uses all the horsepower at his disposal to drive the point home. This event never happened, but the effects remain the same. No created being in heaven or earth could redeem the breaking of the world, and all the effects that ricocheted off as a result. The fall damns the man.

But...

I am sure others will cover the following passages and so I'll end there. Milton's silence struck me, because that very same silence stands before every salvation. Andrew Peterson sums this up beautifully:

"Is anyone worthy? Is anyone whole?

Is anyone able to break the seal and open the scroll?

The Lion of Judah who conquered the grave

He was David's root and the Lamb who died to ransom the slave"

We realise our guilt, are confronted by our shame, our sin covering our hands and feet. Suddenly, we ask, can anyone take this from me? Can anyone save me?

If you're reading this, and you're wondering.

There is. Run to him.

Grace and Peace,

Adsum Try Ravenhill

P.S. Goodness me, that was longer than I intended. Thank you so much Karen for putting this together. What a terrific read.