We are nearly at the end of our long, slow read of Paradise Lost. Next week is the final book of this great epic. After that, Jack Heller will share some reflections about just how “Puritan” Milton was (hint: it’s complicated). Then we will take a break with some lighter fare before beginning our next slow read: The Pilgrim’s Progress.

To discuss Book XI, I’ve decided to shed some of the teacher and put on more of the woman. I want to talk about the aspects of this book that touch me more personally. In some ways, I resonate most with this book of all of them. I suppose that may be true of many readers given that this book brings us face to face with the effects of the fall, a reality none of us can deny.

I find Milton’s conceit—by which he reveals future things to Adam by having the archangel Michael reveal them to him—ingenious and effective. Since we now know nothing but the effects of the fall, Milton re-creates for us some of the shock that we should rightly have in understanding just how wrong the world went as a consequence of sin. Living in first the pre-fallen state and then the post-fallen one, Adam and Eve experienced that shock like we never could. Suddenly, everything has gone wrong.

And the most wrong thing, of course, is death.

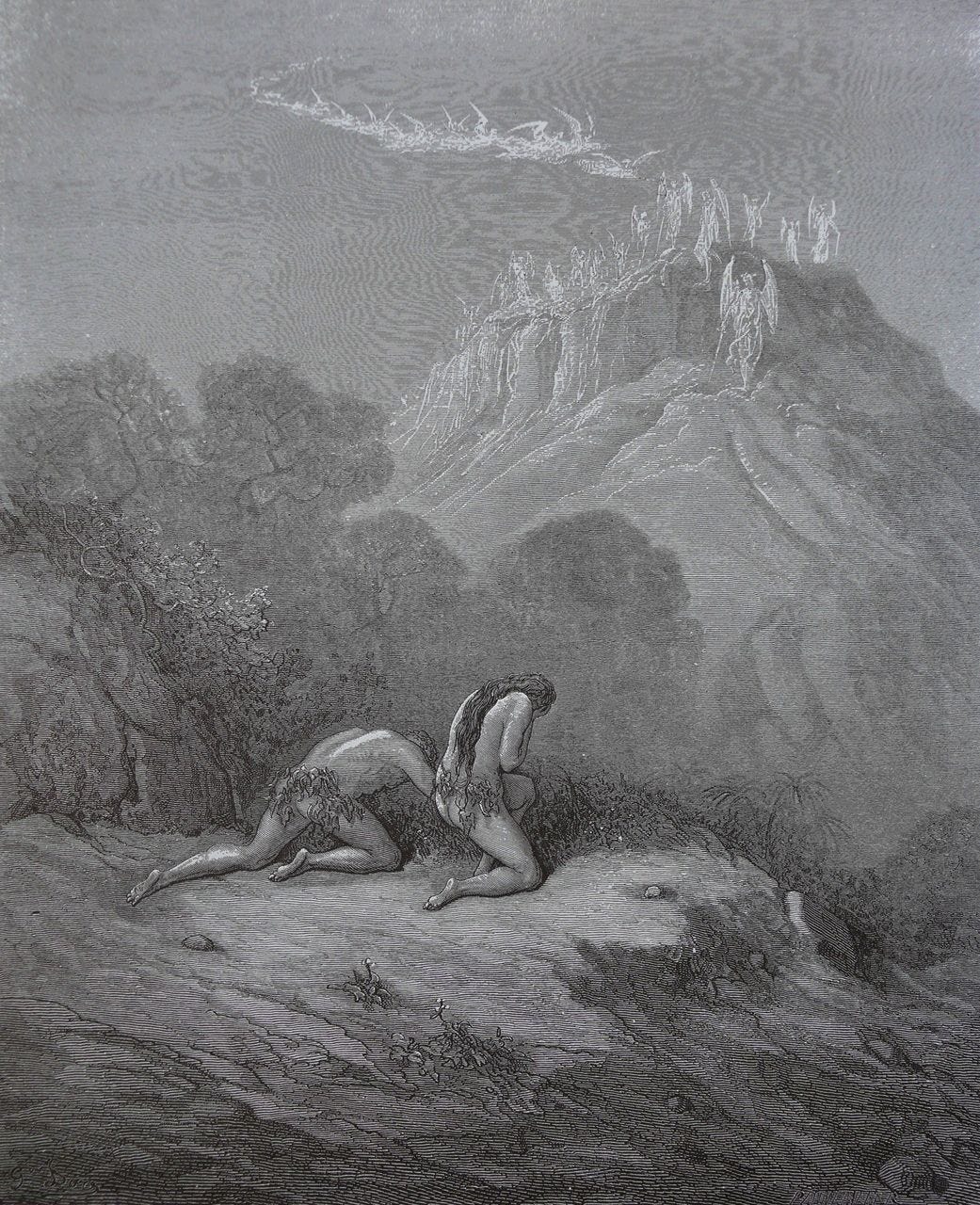

The poem has Adam foresee the murder of and by his future sons, but he sees it as something he doesn’t recognize or understand, having never been exposed to murder before. When Michael gives him the vision of Cain killing Abel, Milton describes Adam watching as brother fells brother. Adam,

… deadly pale, Groaned out his soul with gushing blood effused. Much at that sight was Adam in his heart

Dismayed, and thus in haste to the Angel cried. (446-49)

Adam cries out to Michael,

Alas! both for the deed, and for the cause!

But have I now seen Death? Is this the way

I must return to native dust? O sight

Of terrour, foul and ugly to behold,

Horrid to think, how horrible to feel! (461-65)

Michael goes on to explain death—heretofore inexplicable—in all its guises to Adam in (aptly) gruesome detail:

… Death thou hast seen

In his first shape on Man; but many shapes

Of Death, and many are the ways that lead

To his grim cave, all dismal; yet to sense

More terrible at the entrance, than within.

Some, as thou sawest, by violent stroke shall die;

By fire, flood, famine, by intemperance more

In meats and drinks, which on the earth shall bring

Diseases dire, of which a monstrous crew

Before thee shall appear; that thou mayest know

What misery the inabstinence of Eve

Shall bring on Men. Immediately a place

Before his eyes appeared, sad, noisome, dark;

A lazar-house it seemed; wherein were laid

Numbers of all diseased; all maladies

Of ghastly spasm, or racking torture, qualms

Of heart-sick agony, all feverous kinds,

Convulsions, epilepsies, fierce catarrhs,

Intestine stone and ulcer, colick-pangs,

Demoniack phrenzy, moaping melancholy,

And moon-struck madness, pining atrophy,

Marasmus, and wide-wasting pestilence,

Dropsies, and asthmas, and joint-racking rheums.

Dire was the tossing, deep the groans; Despair

Tended the sick busiest from couch to couch;

And over them triumphant Death his dart

Shook, but delayed to strike, though oft invoked

With vows, as their chief good, and final hope.

Sight so deform what heart of rock could long

Dry-eyed behold? Adam could not, but wept,

Though not of woman born; compassion quelled

His best of man, and gave him up to tears

A space, till firmer thoughts restrained excess ... (467-498)

Few but Milton could make poetry of such ugliness (although Charles Baudelaire comes to mind1).

As readers here know, I have faced death close-up and personal in recent days. As for all of us it moves from the abstraction of ideas and poetry to reality, one way or another, some day or another.

So, too, do the parts of the poem in which Eve and Adam lament the loss of the only home they have ever known. Here is Eve:

O unexpected stroke, worse than of Death!

Must I thus leave thee Paradise? thus leave

Thee, native soil! these happy walks and shades,

Fit haunt of Gods? where I had hope to spend,

Quiet though sad, the respite of that day

That must be mortal to us both. O flowers,

That never will in other climate grow,

My early visitation, and my last

At even, which I bred up with tender hand

From the first opening bud, and gave ye names,

Who now shall rear ye to the sun, or rank

Your tribes, and water from the ambrosial fount?

Thee lastly, nuptial bower! by me adorned

With what to sight or smell was sweet! from thee

How shall I part, and whither wander down

Into a lower world; to this obscure

And wild, how shall we breathe in other air

Less pure, accustomed to immortal fruits? (268-85)

Some of Eve’s lament expresses her new understanding of the perfection and immortality that they will lose. But some of her sorrow is simply in losing what she knows and loves and has held such an important place in her life: the paths she has trod, the flowers she has raised (to which she gave names), and the nuptial bower she shared with Adam.

This hits home (pun intended) for me because I love my home. I love being home. I have lived in many places over the course of my life (three states and many more towns), but the place I call home now has been such for 25 years. I don’t ever want to leave. I offered it up the Lord when I thought, for a while, that he was calling me elsewhere. But that call ended and with it my beloved home was returned to me, my home with its flowers, its trodden pathways, and a well-loved marital bower. I feel you, Eve.2 (I’ve linked in the footnotes to an essay about my home, how I believe God prepared me for and led me to it from the time I was a very little girl. Someday perhaps I will write more about why I thought I would lose it, but did not.)

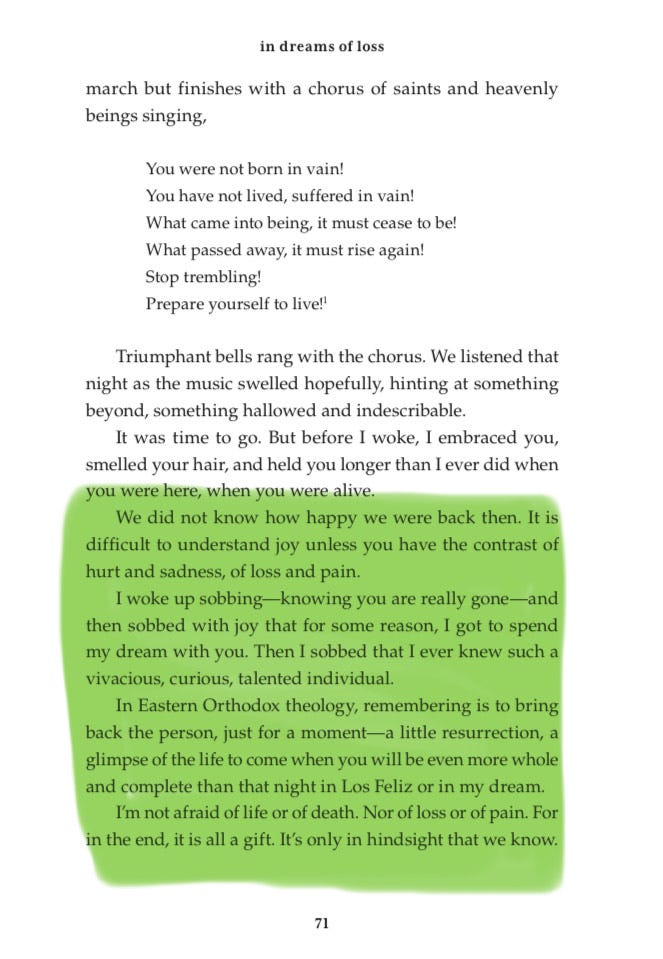

I love the way

(you may recall my author interview with her here from a while back) writes about loss and dreams of loss in her forthcoming book Undaunted Joy. Here she writes about the memories of a friend who died long ago, but that loss is like all great losses. She writes,Adam too, like Eve, waxes sentimental in recalling the place that has been not only home, but also the place in which he has worshiped and communed with God:

This most afflicts me, that, departing hence,

As from his face I shall be hid, deprived

His blessed countenance: Here I could frequent

With worship place by place where he vouchsafed

Presence Divine; and to my sons relate,

On this mount he appeared; under this tree

Stood visible; among these pines his voice

I heard; here with him at this fountain talked:

So many grateful altars I would rear

Of grassy turf, and pile up every stone

Of lustre from the brook, in memory,

Or monument to ages; and theron

Offer sweet-smelling gums, and fruits, and flowers:

In yonder nether world where shall I seek

His bright appearances, or foot-step trace?

For though I fled him angry, yet recalled

To life prolonged and promised race, I now

Gladly behold though but his utmost skirts

Of glory; and far off his steps adore. (315-33)

Adam’s concern is a bit different from Eve’s. He frets that he will not find fellowship with God as he did in Eden. He fears he will be “deprived” of the Lord’s “blessed countenance.”

But Michael assures Adam otherwise:

Adam, thou knowest Heaven his, and all the Earth;

Not this rock only; his Omnipresence fills

Land, sea, and air, and every kind that lives,

Fomented by his virtual power and warmed:

All the earth he gave thee to possess and rule,

No despicable gift; surmise not then

His presence to these narrow bounds confined

Of Paradise, or Eden … (335-43)

God is everywhere, Michael explains, not only in Eden. Not only that, but God charged humankind to steward all of the earth not Eden alone. There is much work to be done. Everywhere. Much joy to be had, too.

Part of the work of stewardship will now be self-stewardship. In several passages, Michael expands on one of Milton’s recurring themes throughout his work: virtue.

Because grace will now contend “with sinfulness of men,” Michael explains, humans must

… learn

True patience, and to temper joy with fear

And pious sorrow; equally inured

By moderation either state to bear,

Prosperous or adverse: so shalt thou lead

Safest thy life, and best prepared endure

Thy mortal passage when it comes. (360-66).

Later, Michael continues in this vein:

… if thou well observe

The rule of not too much; by temperance taught,

In what thou eatest and drinkest; seeking from thence

Due nourishment, not gluttonous delight,

Till many years over thy head return:

So mayest thou live; till, like ripe fruit, thou drop

Into thy mother’s lap … (531-36)

Of course, temperance and virtue are no guarantee of long or pain-free life. But virtue is good character, and good character is the best expression of the good life. This aspect of Paradise Lost is the poetic depiction of Milton’s prescription in Areopagitica: “He that can apprehend and consider vice with all her baits and seeming pleasures, and yet abstain, and yet distinguish, and yet prefer that which is truly better, he is the true wayfaring Christian.”

***

Next week: Book 12

Tentative Zoom meeting date for paid subscribers: I’d like to tentatively set this for Thursday, April 10 at 3:30 p.m. ET or Monday, April at 4:00 p.m. ET. I can adjust but not knowing where everyone is on the globe or in life, I am not sure how well this would work. Please chime in in the comments!

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”3

***

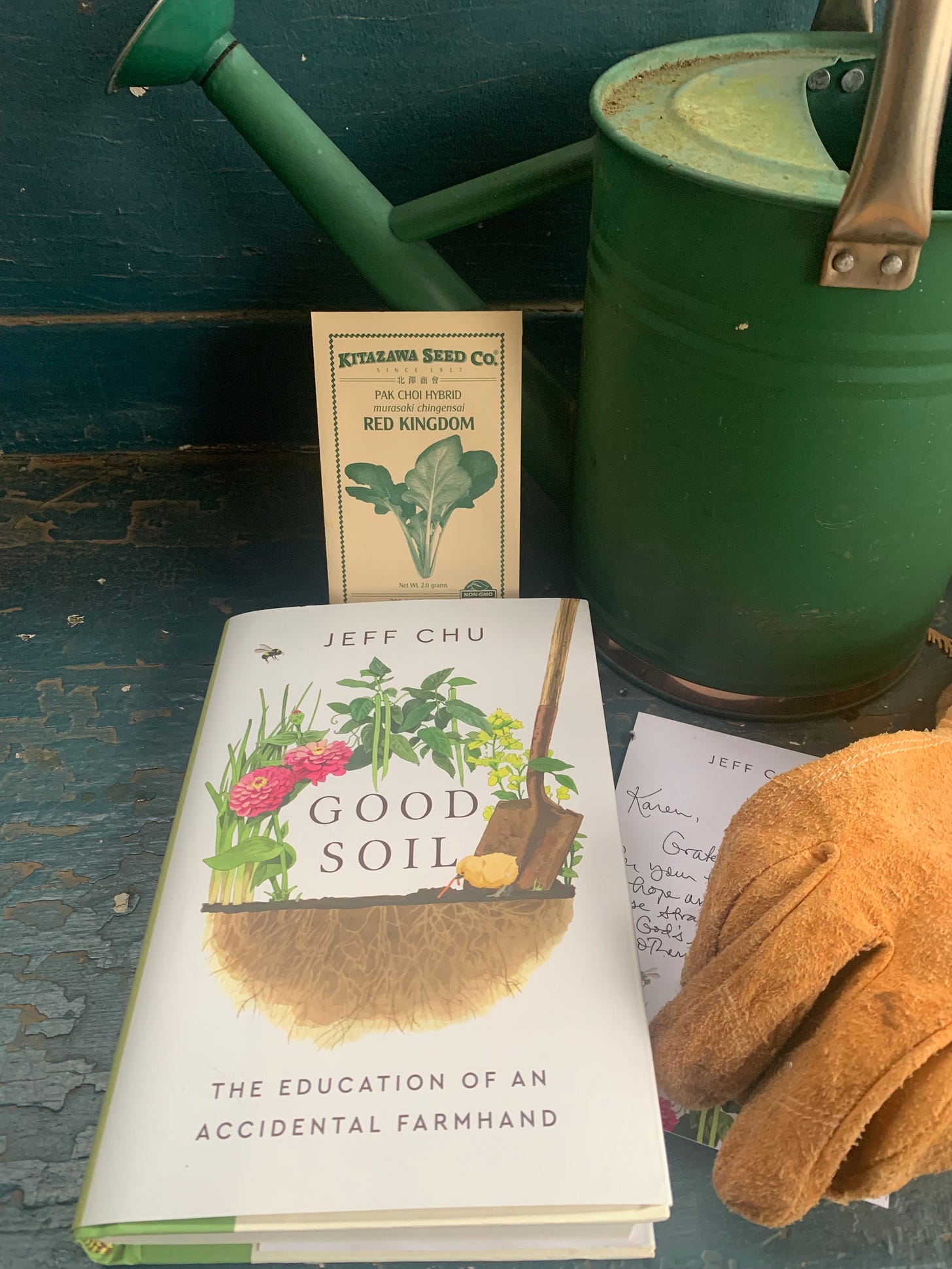

BOOK NOTE:

It is apt on a day in which we are discussing the loss of Eden to share a book that releases today, Good Soil: The Education of an Accidental Farmhand by

. Jeff has been a friend for a long time. I watched a bit of his journey as an “accidental farmhand” through his social media posts over the years. Jeff may have started out as a city slicker, but I know he could teach this country girl a lot about tending to the land and the creatures that inhabit it! Yet, if there is one thing I could say about Jeff (besides the fact that he is a beautiful writer) is that he is one of the kindest people I know.I’ve linked to Baudelaire’s poem “The Carcass,” which is not for the faint of heart. Be warned! But the brief analysis included at the end of the page I’ve linked is helpful to understanding a bit of what is going on in this startling poem.

Here is a link to an essay I wrote some time ago that includes the story of this house and home I love.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

Definitely follow modern medical advice rather than Milton

The wisest words of this section are lines 763-776, which begins:

"better had I Lived ignorant of the future, so had borne My part of evil only, each day's lot Enough to bear";

and continues:

"Let no man seek Henceforth to be foretold what shall befall Him or his children, Evil he may be sure. Which neither his foreknowing can prevent, And he the future evil shall no less In apprehension than in substance feel Grevious to bear".

Even those who foresaw the future in the Bible did not fully understand their visions. God does not burden his children with more than their daily burdens. As the Lord Jesus said, "Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof."

I note than in line 515-16, after Adam's vision of the diseases humanity will suffer, that Milton's Michael says, "Their maker's image then forsook them." As a nurse with experience of helping treat illness in three continents and in patients from every economic strata, I have seen all of the ailments Milton describes generally. In all my patients I have seen the image of God. No matter how broken and distorted the image may be - and by no means were all my patients patient in their suffering - no human is dehumanized by suffering physical or mental illness.

Also, as a lifelong asthmatic, Michael's supposed remedy at line 530 against all these diseases is nonsense. As the Preacher says "Time and chance happens to all". The lung infection which led to my childhood diagnosis of asthma happened when I was five months old. Among my patients I have encountered diabetic, cancer patients, stroke victims, etc. who say to me in bewilderment, "But I did all the right things." A good diet and temperate living will help reduce complications (eg. if I gained too much weight, it would make my asthmatic symptoms more acute), but all of us will will feel the lash of our mortality at some point.