"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”1

Readers, I’m thrilled to bring you a guest post this week by a scholar whose work I’ve long admired and respected: Dr. Alan Jacobs, Distinguished Professor of Humanities in the Honors Program at Baylor University, and a Senior Fellow of the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture at the University of Virginia. You can find out more about him at his website, but let me say a couple of things. Dr. Jacobs is not only a leading Christian literary scholar, but he also writes some of the best cultural criticism around. A book of his that I’ve used in my classes a number of times is How to Think: A Survival Guide for a World at Odds, which I highly commend to you. (The book is more timely now than ever, truly.) But the main reason I asked Dr. Jacobs to join us in this slow read of Paradise Lost is that (unbeknownst to me when we started) his next book is on this great work! Paradise Lost: A Biography (published by Princeton University Press and available for pre-order) releases this May. I can’t wait to read it! But you can read Dr. Jacobs’ insights on Book 10 now:

At the end of the fatal Book IX we left Adam and Eve devoting their time to “mutual accusation”; Milton tells us that “of their vain contest appeared no end.” But appearances can at least sometimes be deceiving.

This tenth book may be divided into five scenes, covering each of the three settings of the poem. This is the first time that we encounter Heaven, Earth, and Hell in one book.

First we return to Heaven, where the Lord God speaks to His angels: “Be not dismayed, / Nor troubled.” Don’t be dismayed, because all has happened precisely as the Father had foretold; and don’t be troubled because you could not have prevented it. An interesting beginning to this book! — the Lord reassuring His servants that He doesn’t blame them. And we are told that the Son, who previously (in Book III) had been proclaimed Redeemer, is now proclaimed Judge. This is the best possible news for the first humans.

So now to Earth — Scene Two. As Adam and Eve argue, here comes “the mild judge and intercessor both / To sentence man,” his voice carried to them “by soft winds” — but instead of rejoicing, they hide. They do not yet know the kindness of God; they only know the terrible promise made to them when they were still innocent, that in the day they eat of the fruit of the forbidden Tree they die.

Milton had an insoluble problem when he communicated to them that promise: When Adam is explaining to Eve about the threat of death, he says, “whatever Death is, / Some dreadful thing no doubt” — but how does he know what a “dreadful thing” is? — he who has never had anything to dread. Now that Adam and Eve have fallen and are just like Milton and us, there are no more difficulties of this kind. Our First Parents know all about dread now: that’s why they hide when they hear the Son’s voice.

(By the way, people who think that Milton was an Arian — that is, one who believes that the Son is not “of one being with the Father” — might need to explain why Adam and Eve, talking with the Son, treat him as God.)

What’s going on here, the Son wants to know, and Adam immediately turns from telling Eve that it’s all her fault to telling the Son that it’s all her fault — but also, kinda, the Lord’s own fault?

This woman whom thou mad’st to be my help,

And gav’st me as thy perfect gift, so good,

So fit, so acceptable, so divine,

That from her hand I could suspect no ill,

And what she did, whatever in itself,

Her doing seemed to justify the deed;

She gave me of the tree, and I did eat.

You have to wonder whether Adam says the “So fit, so acceptable, so divine” part with a sardonic sneer. If you hadn’t given her to me we wouldn’t be in this situation, would we?

To which the Son makes a simple and devastating response: “Was she thy God, that her thou didst obey / Before his voice”? Was she thy God? This is so unanswerable a question that Adam doesn’t even try to answer it; he falls silent, and the Son turns to Eve. And here is where the story, which has sunk lower than the lowest, begins its upward turn — though that may not be obvious at first.

So having said, he thus to Eve in few:

Say woman, what is this which thou hast done?

To whom sad Eve with shame nigh overwhelmed,

Confessing soon, yet not before her judge

Bold or loquacious, thus abashed replied.

The serpent me beguiled and I did eat.

She was not “bold or loquacious,” though Adam had been both. She does not accuse Adam, or justify herself, or blame God. No, she is “abashed” — she immediately sees (as Adam does not) that this is no time for prevaricating or excuse-making. Only the simple truth will do: “The serpent me beguiled and I did eat.”

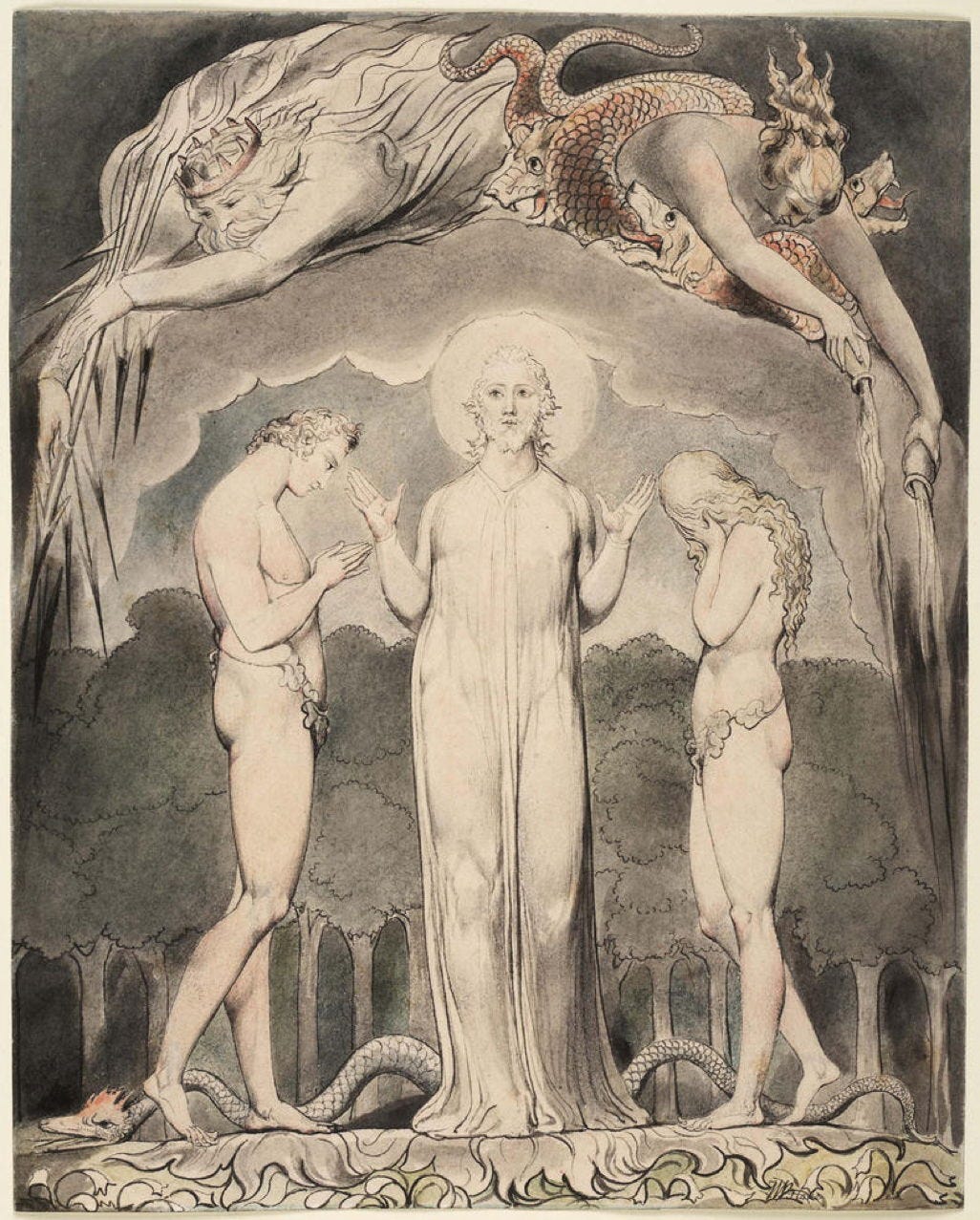

So now, having questioned the witnesses, the Son swiftly does the work of judgment, as described in Genesis 3:14-19. And having judged Adam and Eve … he pities them. Here Milton beautifully expands on Genesis 3:21, where we are simply told that “the Lord God made for Adam and for his wife garments of skins and clothed them.” Milton:

So judged he man, both judge and saviour sent,

And the instant stroke of death denounced that day

Removed far off; then pitying how they stood

Before him naked to the air, that now

Must suffer change, disdained not to begin

Thenceforth the form of servant to assume,

As when he washed his servants’ feet so now

As father of his family he clad

Their nakedness with skins of beasts….

(“The form of servant” comes from Philippians 2:7.) The Son looks upon Adam and Eve and thinks how unprepared they are for the change that is to come: for the labor, and sweat, and pain in childbirth, and, eventually, death. They are but “naked to the air”; he sees their weakness and misery and he loves them and he begins to care for them — a care that he will extend to all their descendents in time to come. It’s a beautiful moment.

Now on to Scene Three: Satan hightails it back to Hell, and we go with him — though pausing to re-encounter Sin and Death and various rebel angels, who sense an opportunity for a serious investment in infrastructure. Death is the first one to get the idea — “with delight he snuffed the smell / Of mortal change on earth” — but it’s the demons who get to work building a bridge from Hell to Earth, to facilitate easy transportation for tempters and tempted alike.

Satan feels pretty great about how all this has worked out. He did everything he wanted and then some; he has been “successful beyond hope”; and all the payback he’ll receive is, he thinks, pretty trivial:

His seed, when is not set, shall bruise my head:

A world who would not purchase with a bruise,

Or much more grievous pain? Ye have the account

Of my performance: what remains, ye gods,

But up and enter now into full bliss.

Milton is not noted for his humor, but the joke here is, if I may say so, a damned good one, and the way you get it is to say that final word thus: blisssssssssss.

So having said, a while he stood, expecting

Their universal shout and high applause

To fill his ear, when contrary he hears

On all sides, from innumerable tongues

A dismal universal hiss, the sound

Of public scorn; he wondered, but not long

Had leisure, wondering at himself now more;

His visage drawn he felt to sharp and spare,

His arms clung to his ribs, his legs entwining

Each other, till supplanted down he fell

A monstrous serpent on his belly prone,

Reluctant, but in vain, a greater power

Now ruled him, punished in the shape he sinned,

According to his doom: he would have spoke,

But hiss for hiss returned with forked tongue

To forked tongue, for now were all transformed

Alike, to serpents all as accessories

To his bold riot: dreadful was the din

Of hissing through the hall….

One of the great passages in the poem! You can just see this “archangel ruin’d,” as he’s called earlier, standing on tiptoe, outspreading his arms, lifting his head, closing his eyes, awaiting the thunderous applause he knows is coming … only to hear the hisssssssssss of “public scorn.” And now, having abused language to abuse innocent creatures, he is deprived of that language, and can only hiss himself.

The fourth scene is a brief return to Heaven, where we get the celebration that Satan was denied: “the heavenly audience loud / Sung hallelujah.”

And then, finally, to Earth, where we find Adam musing on what has transpired, in a long soliloquy worthy of one of one of Shakespeare’s tragic heroes. Back and forth he goes, sometimes blaming God again —

Did I request thee, maker, from my clay

To mould me man, did I solicit thee

From darkness to promote me, or here place

In this delicious garden?

— sometimes wishing that, if he must die, he will die soon; mourning that his sin will afflict his descendents (“Nor I on my part single, in me all / Posterity stands cursed”) but then accusing God of injustice in making the innocent suffer. This final thought leads, for a moment, to a genuine understanding of what he has done:

On me, me only, as the source and spring

Of all corruption, all the blame lights due;

So might the wrath.

This seems a turning point — but a moment later he regrets that he must share the earth “With that bad woman.” He’s a mess: a confused, vacillating mess.

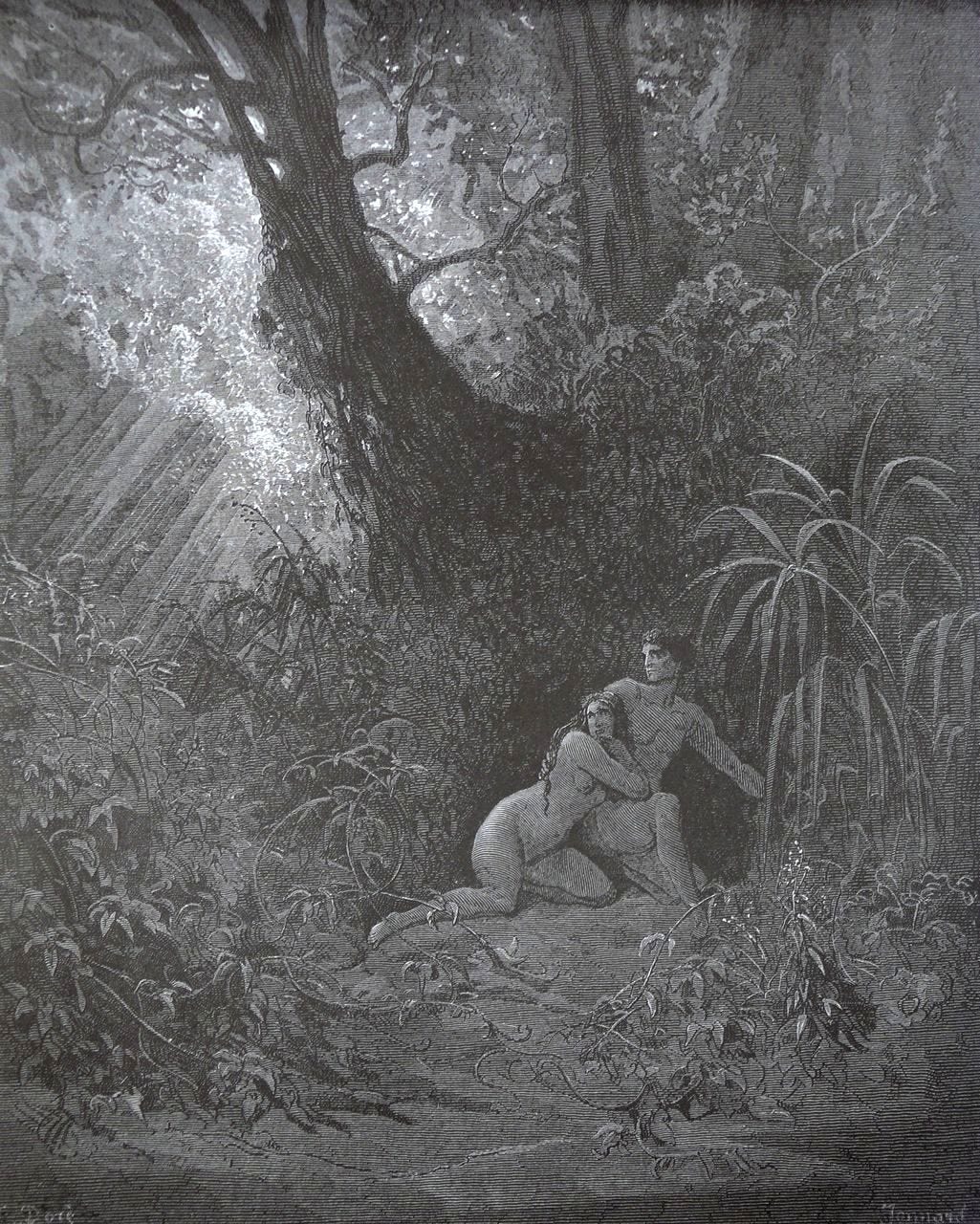

Meanwhile Eve is simply “desolate”; but when she sees Adam so miserable, she “Soft words to his fierce passion she assayed.” That is, she seeks quietly to comfort him — only to receive his rebuke: “Out of my sight, thou serpent”! He pours out his hatred unabated for around forty lines.

And then something happens that, every time I read it, brings tears to my eyes. To understand it, you have to understand how in their unfallen state Adam and Eve spoke to each other. She calls him things like “My Author and Disposer”; he addresses her as “Daughter of God and Man, accomplished Eve.” The courtesy is inventive and elaborate. But now listen to Eve, in what I believe to be the single greatest speech in this great poem:

Forsake me not thus, Adam, witness heaven

What love sincere, and reverence in my heart

I bear thee, and unweeting have offended,

Unhappily deceived; thy suppliant

I beg, and clasp thy knees; bereave me not,

Whereon I live, thy gentle looks, thy aid,

Thy counsel in this uttermost distress,

My only strength and stay: forlorn of thee,

Whither shall I betake me, where subsist?

While yet we live, scarce one short hour perhaps,

Between us two let there be peace, both joining,

As joined in injuries, one enmity

Against a foe by doom express assigned us,

That cruel serpent: on me exercise not

Thy hatred for this misery befallen,

On me already lost, me than thyself

More miserable; both have sinned, but thou

Against God only, I against God and thee,

And to the place of judgment will return,

There with my cries importune heaven, that all

The sentence from thy head removed may light

On me, sole cause to thee of all this woe,

Me me only just object of his ire.

“Forsake me not thus, Adam” — the most heart-rending cry imaginable. We may not have one more hour of life remaining, she says; shall we spend it in “mutual accusation”? She does not defend herself; she does not point out the obvious injustice of his denunciation, his refusal to take responsibility, his pointless hatred of one who is “already lost” and even “more miserable” than he is; indeed, she wishes to name herself “sole cause … of all this woe,” and pleads that the Lord will make her — “me me only” — the “object of his ire.”

It is grace to the graceless. It is mercy to the merciless. Eve is the first follower of the Son who pities the broken. All she asks is this: “Forsake me not thus, Adam.” And, after all, he does not forsake her. So the long healing begins.

***

WHAT’S AHEAD:

Just two more books to go and we will have read together one of the world’s great masterpieces: Book 11 and Book 12.

I will work on a date and time for a Zoom meeting. I wonder if late afternoon in my time zone (Eastern) might be best for folks who are across time zones?

We will read The Pilgrim’s Progress together in coming weeks! We’ll rest a bit after finishing Paradise Lost. But if you want to plan ahead, you might consider getting a good edition for yourself. As the second most published book in the world (after the Bible), there are many. One word of caution is that many of these are redacted, abridged, and modernized—so there are great variations. This is the old copy I use, from Oxford World Classics. I’d say you are safe with any unabridged edition with original marginalia (and editorial notes also help). Note that some editions are modernized and take various liberties in so doing.

Finally, I want to welcome the many new subscribers that have joined us here at The Priory. It is my desire to keep all my posts free to any readers, but I can do that only because of the support of those of you who are able to become paid subscribers. Your support makes this work possible for me to do and to make available to the world. Please consider becoming a paid subscription if you are able. (Group discounts are available when two or more sign up together.) Paid subscribers get to comment and, truly, it is our discussions that make these posts as rich as they are. Thank you.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

Thank you very much for this. I can tell by how you write about this book that you are passionate about it.

It is fascinating that before his fallen state, Milton wrote Adam and the Angels dialogue in what seemed to me as a "lofty" speech. It's English, but I almost did not recognize it, as if it was over my head. Once Adam, in his fallen state, began to talk about death, I was like, "There's the language I understand." I feel Milton did this deliberately.

On another note, I appreciated how you treated Eve in this essay. I liked your interpretation. In my opinion, the most interesting part of this book is lines 783-795.

Yet one doubt

Pursues me still, lest all I cannot die,

Lest that pure breath of life, the spirit of man

Which God inspired, cannot together perish

With this corporeal clod; then in the grave,

Or in some other dismal place, who knows

But I shall die a living death? O thought

Horrid, if true! yet why? it was but breath

Of Life that sinned; what dies but what had life

And sin? the body properly hath neither.

All of me then shall die: let this appease

The doubt, since human reach no further knows.

For though the Lord of all be infinite,

Is his wrauth also?

I think what is so appealing to me about this section is that it is so very human. He is in despair, and he has questions and wonders about death- I can empathize with that. Many of us have been there.

And then there is Eve. One of the most tender parts of her speech to me is when she suggested suicide in lines 1001-1006:

with our own hands his office on ourselves;

Why stand we longer shivering under fears,

That show no end but death, and have the power,

Of many ways to die the shortest choosing,

Destruction with destruction to destroy.

She sounds so strong, but I think she is terrified. To be at the place of wanting to attempt is a very vulnerable feeling. As a reader, Milton takes us on a journey to the bottom of her despair. It makes me want to give her a big hug.

Milton's imagination is undoubtedly fertile. The description of personified sin and death emerging from hell to conquer the earth is especially chilling. But in Genesis 3, after the consequences declared by God*, Adam's first response is to name Eve (before this, Eve is simply named Woman). In the Hebrew, the name Eve is Chavah (Eve is an Anglicized transliteration of the name), meaning life, because, Genesis 3:20 says, "she was the mother of all living". That is the Biblical Adam's first recorded response to the heavy consequences of sin, recognition that the woman God gave to him will bring all other humans into life.

But in Milton's version, Eve is already named, and his Adam and Eve discuss the possibility of choosing to die without offspring. They eventually decide against it in a weak and vacillating way, but Milton's portrayal is ultimately pessimistic, lacking the hope of the Biblical account. The reasoning portrayed in their discussion about whether to die without offspring reminds me of those who criticize refugees or those living in oppressive conditions for having children, saying things like "They should know better than to have children in that environment." But that is what humanity does, our hope forever outweighs our despair, or we would simply lie down and die after each disaster in which we find ourselves. In Genesis, Eve names her firstborn in the hope that he is the promised seed that should crush the serpent. He isn't of course, he becomes the first murderer, of his brother no less, but nevertheless that hope continues. Eve has her third named son, Seth, after she looses both Cain and Abel. She never lost hope, and she was right to not do so, for from Seth is traced the earthly ancestry of Jesus Christ.

*N.B. Arianism does not deny the Son could be called God in some sense, but rather says the Son was created, making the Son less than the Father: (https://hardonsj.org/arianism-denial-divinity-jesus/), which Milton indisputably says not only in PL, but also in other writings.