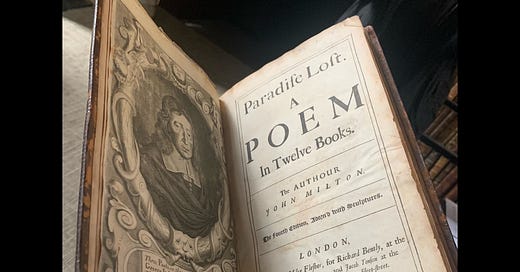

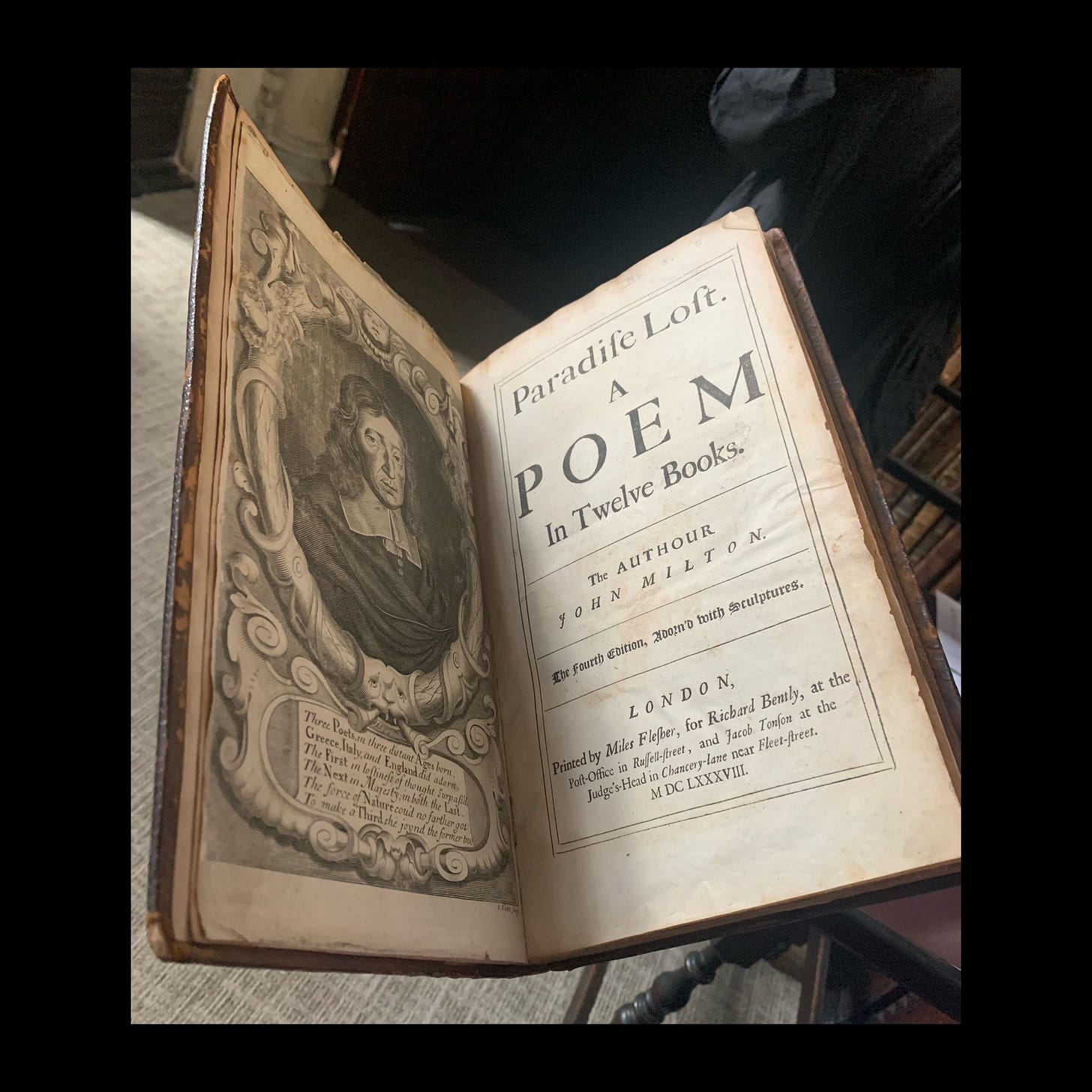

[This picture and the next were taken by me at St. John’s College Library at Cambridge University when I was able to visit last summer. This is a 1688 edition of Paradise Lost, the first illustrated edition.]

What though the field be lost?

All is not lost—the unconquerable will,

And study of revenge, immortal hate,

And courage never to submit or yield:

And what is else not to be overcome?

That glory never shall his wrath or might

Extort from me. (1. 105-11)

So declares Satan, the first character to speak in Paradise Lost, the character that has most fascinated readers of the poem for centuries now—the spiritual entity that has enraptured real folks for time immemorial.

Yes. The most recurring question for modern readers is this one: is Satan the hero of the poem? I contend that this is indeed a modern question, one that modern readers ask not so much because of how Milton portrays the character but because of how much that portrayal resonates with values we have today that weren’t valued quite so much (but perhaps a little?) in Milton’s day or by Milton.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves here. This question will linger throughout our discussion, however, which is why I wanted to begin with it. Like Milton, I have begun in medias res—in the middle of things, a prominent epic convention Milton follows here. More on epic conventions to follow.

For now, let’s get back to the beginning. My pedantic self wants to try to prepare you and help you with the reading and discussion of this massive, complicated work. I proposed working through a book of the poem a week. I realize now in sitting down to write this first installment that we could spend a week on a couple of lines. Seriously. So the first pedantic point I want to make is this: we will not even scratch the surface of this great epic here in this series. But I do think we will think, and learn, and delight quite a lot. Yes, I do. So let us do what we can. ‘Tis better to have caught a glimpse of genius in reading Paradise Lost than never to have read it at all. (Apologies to Alfred, Lord Tennyson.)

The first thing you will notice upon beginning is that each book begins with an “argument” laid out for us by Milton himself. Read it! Yes, it is a summary of what happens in the book, and Milton wanted us to have that summary. The idea of a “spoiler alert” is for works in which “what happens” (plot) is important. Well, here’s a spoiler alert for you: Adam and Eve eat the forbidden fruit and are expelled from the Garden of Eden. Paradise lost. Milton knows we know the story. What he wants us to enjoy is the language and imagination he employs in telling the story in epic, poetic form. Of course, he adds a tremendous amount to the material provided in the Bible, so the “argument” clues us in on that so that we can better focus on the language, the form of the story, and not just its content. So read the argument.

The next thing you will notice is that Milton’s poem doesn’t rhyme. Indeed, Milton says in his prefatory remarks about the verse that rhyme is “the invention of a barbarous age.” Ouch. (Well, he protests a little too much since we know he uses rhyme in other poems.) Paradise Lost is written in blank verse: unrhymed iambic pentameter. However, this isn’t just any blank verse. Milton employs this technique in a truly “epic” way: his thoughts don’t just run into one another for two or three lines; they often take a dozen lines or more just to complete a sentence or clause. The effect of this is to pull you in and keep you reading and reading until you are drawn far into the poem, passage by passage.

Now the tricky part of this technique is that Milton’s “sentences” aren’t just long, but they are scrambled in syntax as well. Typical English sentences begin with the subject and are followed by the predicate with other phrases and clauses tacked on: I kicked. I kicked the ball. I kicked the ball with glee. I kicked the ball with glee to my friend. I kicked the ball with glee to my friend in the yellow shirt. I kicked the ball with glee to my friend in the yellow shirt who was standing on the moon next to a pine tree covered with tinsel. Milton would do this: To my friend in the yellow shirt, standing on the moon, next to a tinsel-covered tree of pine, the ball I kicked with glee. Or something like that. You get the idea. Just as with my simple sentence with irregular syntax you must identify the subject, predicate, and objects, you must do the same with Milton.

However, this irregular syntax isn’t just a word game. It is a way of bringing emphasis and different slants of light to key images, words, and ideas. So pay attention not just to what Milton does, but how he does it and what the effect of that is.

The easiest place to begin to see this technique is in the opening lines. Notice that the first sentence is 16 lines long. Notice the opening lines signify prepositional phrases: “of” this and “of” that. Notice the grammar of the whole sentence. The sentence is an imperative: it exhorts the “Heavenly Muse” to “sing” of these things. You just have to find the implied subject and predicate in the middle of that long sentence. (The work is worth it, I think!)

And with the invocation of the Muse, we have another epic convention. Milton invokes this convention but Christianizes it. These aren’t the pagan muses of Greek myth, oh no. The heavenly muse is the Holy Spirit, and Milton invokes the Spirit’s aid in composing this great work. The purpose, the poet states plainly in lines 25 and 26, is to “assert Eternal Providence / And justify the ways of God to men.”

And when the story begins, it begins in hell, named in line 756 with a word of Milton’s coinage: “pandemonium,” literally, demons everywhere.

These are the demons cast from heaven for their rebellion against God. Milton follows another epic convention in cataloging many of them by name and ample description. Among them is Beelzebub, whom Satan sees in his degraded state and laments,

O how fallen! how changed

From him who, in the happy realms of light

Clothed with transcendent brightness, didst outshine

Myriads, though bright! (1. 84-87)

The demons are rousing themselves in the aftermath, and led by Satan, they are defiant, as we see in the lines with which I opened this installment.

Satan goes on to rally them in lines 157-65:

Fallen Cherub, to be weak is miserable,

Doing or suffering: but of this be sure—

To do aught good never will be our task,

But ever to do ill our sole delight,

As being the contrary to his high will

Whom we resist. If then his providence

Out of our evil seek to bring forth good,

Our labour must be to pervert that end,

And out of good still to find means of evil …

Let me draw your attention now to lines 192 to 220. This long passage describes Satan (in both appearance and character) and does so using what has come to be called (aptly) a Miltonic simile (a very long comparison). These lines are long, and bulky, and cumbersome—just as Satan is described as he lies prone on the ground, “extended long and large” (line 195). As the mythical, terrible creatures described in the next few lines were, “so” (line 209) is the Arch-Fiend. (Remember that to say one thing is “as” another is a simile.) This simile is serpentine in every way.

Read these lines again and closely. Does this monster seem like a hero to you?

I will end my thoughts here by noting again how little I can get to in a format such as this.

However, I do think that together we can bring much more to the table. Many have expressed interest in joining this slow read of Milton’s epic masterpiece. I am thrilled! I encourage all of you who are part of our smaller community of paid subscribers to participate (as you always do) by commenting—any way you wish, of course. But here’s what I would love for you to do: drop a line or a passage or a phrase from Book 1 that struck you. I can’t offer more than a few lines each week. But each of you can point readers to more. What a gift that would be if you are so able to offer it. (How I wish we were all in a room together! Alas, the virtual one will have to do.)

Next up: Book 2. (Find it online here.)

***

BOOK NOTE:

It happened unexpectedly! Usually, I plan a big reveal of the cover and title of my latest book. But, alas, holidays and death got in the way, and my book got out on the internets where a delighted reader discovered it and spilled the beans! So here it is officially: You Have a Calling: Finding Your Vocation in the True, Good & Beautiful. Coming in August but available for pre-order now (and pre-orders really, really help).

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”1

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

You’re right, Karen, that Milton’s sentences are typically very long and syntactically complex. But sometimes he can fire off a short one that is downright aphoristic, e.g., lines 254–55:

The mind is its own place, and in itself

Can make a Heav’n of Hell, a Hell of Heav’n.

(I’m reading the Hackett edition of Complete Poems and Major Prose edited by Merritt Hughes, in which the apostrophe often appears to indicate elision of a syllable for the meter’s sake.)

These two lines could be taken as summing up the tragic confusions that humanity’s fallen state is prone to—and the mind itself being a “place” is evocative too, of the wandering over an interior landscape of which we are all capable.

Karen, I'm reading my son's edition of "Paradise Lost," edited by David Scott Kastan -- and he does not point out something that stood out to me. Could I be over-interpreting? When Milton invokes the Holy Spirit in lines 19-22, he writes,

"Instruct me, for thou know'st; thou from the first

Wast present, and, with mighty wings outspread,

Dove-like sat'st brooding on the vast abyss

And mad'st it pregnant."

Professor Kastan notes the reference to Genesis 1:2 when the Spirit hovers over the waters; but he does not mention Milton's foreshadowing of Jesus. Not only does the Holy Spirit appear as a dove at Jesus' baptism, but Milton's use of the word "pregnant" is -- well, pregnant. Obviously, the dark abyss is made expectant and full of possibility here -- as in the phrase "a pregnant pause" -- but also, in the New Testament, it is this same Holy Spirit that makes Mary pregnant with Jesus. Even at the beginning of this poem -- before the need has arisen -- our salvation is at hand.