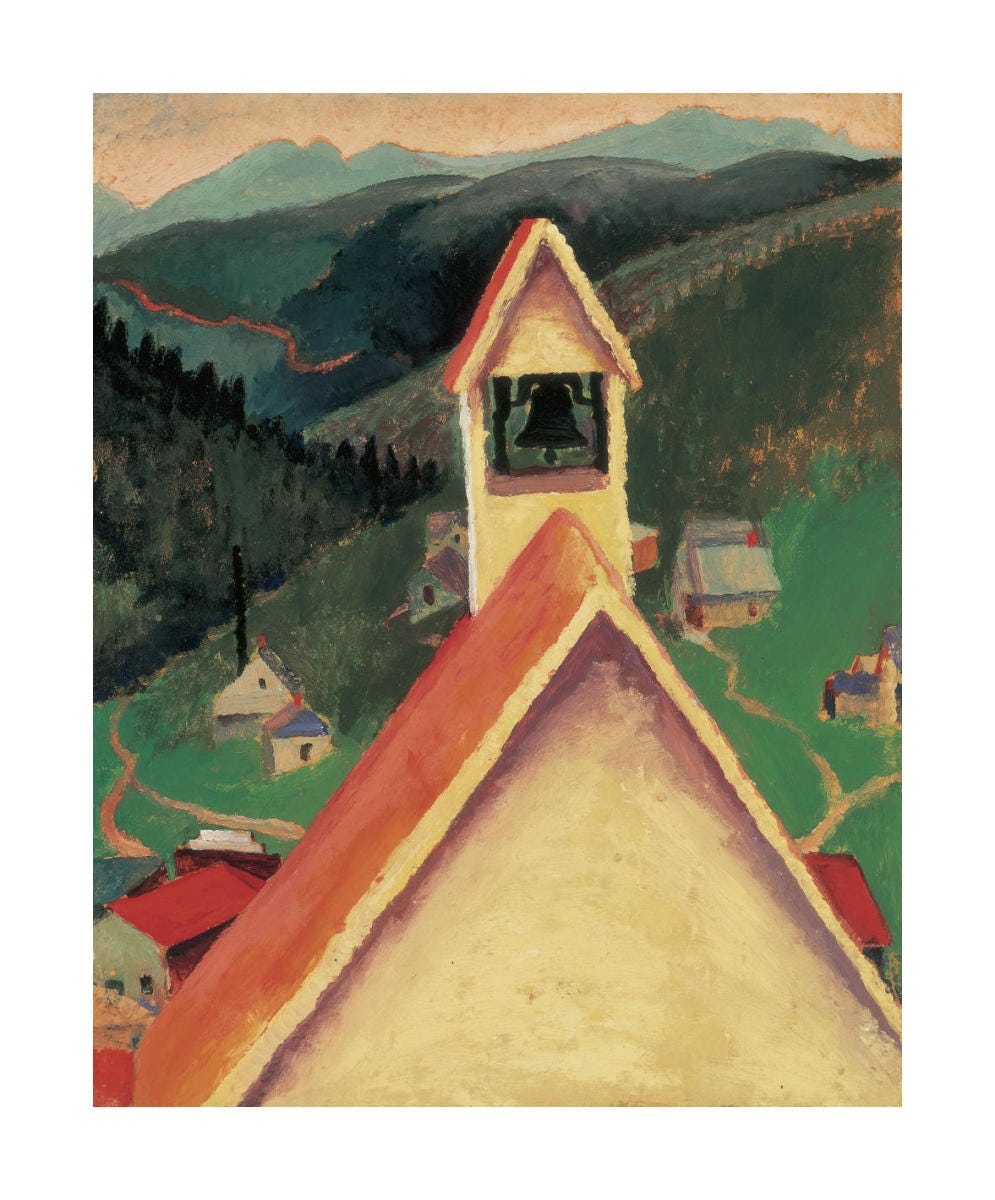

[Georgia O'Keeffe. Church Bell, Ward, Colorado, 1917]

John Donne’s “Meditation 17” is part of his larger work the shortened title of which is Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions. Donne wrote this book-length collection of devotions in 1623 while he was recovering from a serious illness—one that brought him close to death. Unlike many of his poems, this work of prose was published during Donne’s lifetime, the next year, in fact. By this time in his life, Donne was well-established in both church and state. He had been appointed Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral in 1621 and his sermons were becoming widely acclaimed. Donne dedicated Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions to the then-prince, Charles, son of King James 1, who would later become King Charles 1.

Each devotion in the collection consists of three parts: a Meditation, followed by an Expostulation, closed by a Prayer. The twenty-three devotions cover each day of Donne’s illness and are arranged chronologically in the book (which you can find in its entirety online here). While Donne uses the devotions to reflect on his own harrowing experience, he also sees his illness as an occasion for reflecting on the human condition more generally, one captured most powerfully in the essay he wrote on the seventeenth day of his sickness, “Meditation 17.”

Famous for the line, “never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee,” this mediation is justly the most well-known from the collection—but barely just. There are many riches within the entire work, too many to cover here.

So before moving on to this long-promised meditation, let me quote from one of the later ones, “Meditation 22.” This one is centered on the theme of the endless work required of the physicians attending to Donne’s sickness and the sickness of all humankind for each of us has a mortal body riddled with weakness and disease. “How ruinous a farm hath man taken, in taking himself!” Donne laments, “How ready is the house every day to fall down, and how is all the ground overspread with weeds.” This is the English language at its finest: how ruinous a farm man hath taken, in taking himself!

Now, to continue on to the work at hand, let me note that it takes less than five minutes to read “Meditation 17,” so I hope you will read it in its entirety. You can also listen to Orson Welles do a fine reading here. I will highlight a few of my favorite passages in this essay and discuss them. But truly, the best approach to appreciating this devotion is simply to read it slowly, savor it, and read it again and again. It speaks for itself.

First, just a reminder that the imagery of the bell tolling in this context refers merely to a church bell (or perhaps that of the horse-drawn hearse) ringing for a funeral procession. (Recall that the young rioters in Chaucer’s Pardoner’s Tale heard that sound at the start of the tale. This was a common event.)

The opening lines offer the simple musing that it is easy when one is reminded of mortality to think of it as someone else’s mortality rather than our own. (It reminds of how we sit in church and hear a sermon and think, “Oh! So-and-so needs to hear that” — when in fact we need to hear it!) Then the seemingly sudden shift to talk of the universality of the church is not a shift at all, but rather a similar point (that leads to the larger point): death, like the church, is universal. It is for all, whether we realize or accept that fact. Moreover, another person’s death—just like another person’s baptism—affects us all.

This point is continued later in the devotion in the second half, which begins with its most famous line. This passage is worth quoting and reading so that we have all these famous parts in context:

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend's or of thine own were: any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bells tolls; it tolls for thee.

As beautiful as this passage is, it’s not my favorite part of the devotion. I will get to that in a little bit.

First, let’s consider the final part of the devotion where Donne employs another brilliant metaphysical conceit—if you thought that such conceits were limited to poetry, you were mistaken. This entire devotion—written in prose—is filled with conceits and the final one compares affliction to treasure (or money, or gold, or currency). Now, before you even get caught up in Donne’s meticulous expansion of the conceit, just stop and ask for yourself: how is suffering or affliction valuable? You might answer that question differently depending on your religious beliefs, particular doctrines, or worldview. But it is a question that must be asked because suffering is part of the human condition for all. We might differ on the answers but we all must ask the question.

I’m terrible with all things money-related (and therefore money metaphors), but it seems to me that Donne is contrasting currency in its symbolic sense versus its real value. “Currency” in terms of money is not even a term I understand. I don’t understand the “gold standard” or bitcoin or any of it. But I do understand that Donne is saying it is hard to see the value of suffering in the moment. But if suffering – or the tolling of the bell that reminds us of suffering – brings us to God, that is its ultimate value.

But my favorite part of this devotion is earlier, in the first half. It is where Donne employs another conceit, one that compares death to translation from one language to another. How could the book lover and language lover that I am (and that I know many of you dear readers are as well) not love, love, love this imagery?

… all mankind is of one author, and is one volume; when one man dies, one chapter is not torn out of the book, but translated into a better language; and every chapter must be so translated; God employs several translators; some pieces are translated by age, some by sickness, some by war, some by justice; but God's hand is in every translation, and his hand shall bind up all our scattered leaves again for that library where every book shall lie open to one another.

Death is a translation; God uses many translators. But God binds up all of our pages, and places us into that eternal library, where we will read and know all things.

Next week: Donne’s “The Bait” (by request)

Then: “Show Me Dear Christ, Thy Spouse So Bright and Clear”

***

Speaking of libraries, those of you following me on social media may be watching the progress being made on the little library my husband is building next to our house. I will plan to devote a post to that—the process and the outcome—once it’s all done. For now let me just say, what a gift! A library!

***

BOOK NOTE:

I “met” Rusty McKie a couple of years ago when he interviewed me on his podcast. (You can listen to it here.) I do a lot of podcasts. (And I do mean a lot!) But my conversation with Rusty really stands out to me even all this time later. Rusty was deep and sensitive, thoughtful and solid. I remember being very moved by his character and personality.

And now he has a new book that reflects all these things: The Art of Stability: How Staying Present Changes Everything. (The Art of Stability also is the name of his podcast.)

If you are interested in hearing a voice and/or reading the words of someone who flies under the radar, does the long and steady work, and is the real deal, Rusty is your guy.

I’m grateful for him and his new book.

***

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”1

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

I agree that the conceit of "translation" is marvelous. But I think Donne is having even more fun here with the double meaning of "translate." Just as old a meaning as "convert from one language to another" is "take or convey (a living or deceased person, a soul, etc.) to heaven or the afterlife" (OED, II.10). So when he writes that "some pieces are translated by age, some by sickness, some by war, some by justice," he means something both literal AND metaphorical. Some people die of age, some of sickness, some by war, some by justice (executed upon legal judgment). The whole passage vibrates back and forth between the two meanings, of our literal death on one hand and of our being bound in God's book on the other.

"Moreover, another person’s death—just like another person’s baptism—affects us all."

I was wondering whether to share this, but I am getting baptised! (6pm Sunday 18th August in Wales, UK) zoom link: https://us06web.zoom.us/j/83741848261?pwd=Cyk6qo7AiJJpWjSnb3ermR14NKp1ib.1

Meeting ID: 837 4184 8261

Passcode: 612468

All welcome to tune in! Glad to share the good news - Jesus is evangelizing, saving and reviving across the world.

Thanks for the articles, keep publishing!