[photo by Karen Swallow Prior]

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”1

This poem might, in one sense, be one of the easiest of Donne’s to understand. Part of that is because so many of its words and ideas are repeated, driving home the language, theme, and imagery. This repetition—along with the meter, alliteration, assonance, and the simplicity of the words themselves—is what gives the poem its hymnlike quality. Written during a severe illness in 1623, Donne had it set to music, in fact, and it continues to be performed to this day. (I will post links to a couple of those performances below).

In his Life of Dr. John Donne, Izaak Walton says this about the hymn:

[Donne] caused it to be set to a most grave and solemn tune, and to be often sung to the organ by the Choristers of St. Paul’s Church, in his own hearing; especially at the Evening Service; and at his return from his customary devotions in that place, did occasionally say to a friend, "the words of this Hymn have restored to me the same thoughts of joy that possessed my soul in my sickness, when I composed it. And, O the power of church-music! that harmony added to this Hymn has raised the affections of my heart, and quickened my graces of zeal and gratitude; and I observe that I always return from paying this public duty of prayer and praise to God, with an unexpressible tranquility of mind, and a willingness to leave the world."

When I say the poem is perhaps one of Donne’s simplest to understand, by no means do I mean that it lacks in his wit and brilliance. In fact the obvious theme of the poem—seeking God’s forgiveness for sin—makes it easy to miss the treasures of language that make this poem so rich and moving.

Before looking at each stanza, let me point out the puns (a form of wordplay Donne loved so much) that are key to grasping this layered richness.

First, each time the poem says the phrase “thou hast done,” it has two meanings. It refers most literally to God being done (or not done) with the ongoing need to forgive the speaker for his sins. Second, more subtly, Donne is punning on his name. So this phrase also signifies God’s possession of Donne himself: thou hast Donne.

The poem is also punning on the name of Donne’s wife, Ann More. As I explained in my earlier post, Donne was imprisoned for secretly marrying Ann against the wishes of her family, and the two suffered for years because Donne’s political career was ruined. So the word “more” in the last line of each stanza can also be read as a pun on Ann’s name, “More” (which Donne did other times as well).

Reading these lines with all of these meanings in mind adds a great deal to the depth of the poem’s searching questions and its beautiful language.

The poem is a hymn—or prayer—to God, the “thou” to whom the entirety is addressed.

Four times the speaker asks, “Wilt thou forgive” and identifies four categories of sin for which he seeks forgiveness: original sin, the sin he, along with all humanity, is born with, which started when his life began (lines 1-2); the sin he continues to commit and cannot seem to stop even though he hates this sin (lines 3-4);2 the sin by which he caused others to sin, even introducing such sin to them (lines (7-8); and the sin he avoided for “a year or two, but wallowed in” for many more (lines 9-10).

As he goes through this catalog of shame, he stops twice, in seeming despair, to tell God, “Wait. I have more.”

Two stanzas spent seeking forgiveness are then followed by a final stanza that is a confession.

I think the confession translates well into evangelical jargon, by which I mean to make it more relatable, but by which I do not mean to reduce it to this formula. Basically, Donne confesses the fear that he is not (or will not be) saved. This fear could be because he will die with unconfessed sin. It could be because he never was saved. It could be because Jesus isn’t real or eternal after all. The language the poem uses to express this fear that death will be for him just a “perishing on the shore” does not state the specific doctrinal point that would result in this eternal death. And that is why this confession is so powerful, poignant, and universal. Such doubt is something we all experience. It is so refreshing to me to see these eternal human questions asked in language that is outside my place and time. I love language but it reminds me that we are always bound by it.

“Swear by thy self,” Donne begs (asking God to “swear by God”—heh!) that Jesus (his Son who is also likened to the Sun) shall shine after death as he does now in life. Swear that this Jesus he believes in and who promises forgiveness in sins is real. If that be so, “thou hast done” and “I fear no more.”

How can such a poem by a man so different from me, living in a time so different from mine, using language so different from my own speak, so exactly the questions of my own soul?

I am undone.

Wilt thou forgive that sin where I begun,

Which was my sin, though it were done before?

Wilt thou forgive that sin, through which I run,

And do run still, though still I do deplore?

When thou hast done, thou hast not done,

For I have more.

Wilt thou forgive that sin which I have won

Others to sin, and made my sin their door?

Wilt thou forgive that sin which I did shun

A year or two, but wallow'd in, a score?

When thou hast done, thou hast not done,

For I have more.

I have a sin of fear, that when I have spun

My last thread, I shall perish on the shore;

But swear by thyself, that at my death thy Son

Shall shine as he shines now, and heretofore;

And, having done that, thou hast done;

I fear no more.

Here’s a performance arranged by Benjamin Britten:

Choir performance with music by Howard Helvey:

A beautiful solo performance, arranged by Pelham Humphrey, the original composer:

I tend to be a purist in most things, but this folk version is quite beautiful:

Simon Russell Beale introducing and reading the poem:

Up next:

· “The Flea”

***

BOOK NOTE:

If you’ve followed me for any length of time, you know a little (or a lot) of how confusing and dismaying these days have been for me (and so many others) in the church. It has been disorienting to have the veil lifted and to see underneath that what I thought all along was religious has really been political. In a strange way, it has been my study of history through literature that has given me the perspective I need to reorient myself and to remember that none of this is new. We need only to look at the life and times of John Donne to see another time and place where what was supposedly religious was, for the most part, political.

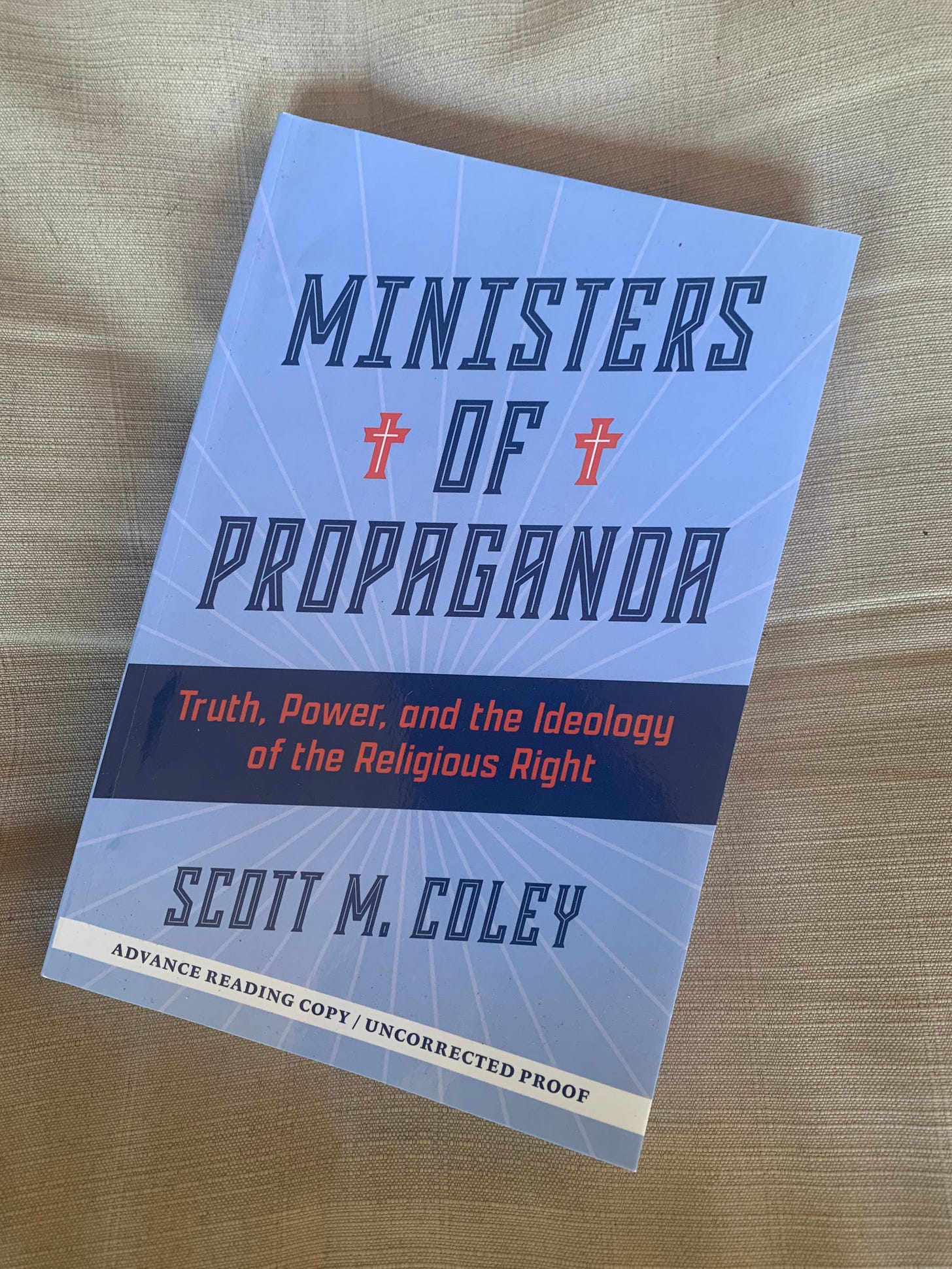

This week’s book note, appropriately then, features a new release by my friend, Scott Coley: Ministers of Propaganda: Truth, Power, and the Ideology of the Religious Right.

I’m only partway through, but I have to tell you, this book is eye-opening. I trust Scott in a particular way because he shares the same background as me, and some of the same institutional experiences. He gets it. Slowly, I am getting it, too.

NOTE OF THANKS: The Priory has seen a lot of new subscribers and supporters over the past couple of weeks. It really means a lot to see this and to see so many of you who started on this journey with me stay, read, and share these posts. It will be coming up soon on a year’s time of this, and it makes me reflective and thankful. I expect I will write some of those thanks and reflections on that anniversary. But for now, I just want to express my deep, deep gratitude. It’s not too much to say that in some ways, you all have saved my life.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

This category of sin beautifully reflects the ones Paul talks about in Romans 7:15-20 when he talks about the struggle of doing what he hates to do—as we all do from time to time: https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Romans%207%3A15-20&version=NIV

I had never read this poem prior.

Beautiful expression of twin fears that he is not worthy of salvation and that his faith in the idea of salvation was misplaced. I love this series!

I think the phrase "But swear by thyself" is a reference to passages in the New Testament book of Hebrews, in chapters 6 & 7. Chapter 6:13-20 in the King James version:

'For when God made promise to Abraham, because he could swear by no greater, he sware by himself, Saying, Surely blessing I will bless thee, and multiplying I will multiply thee. And so, after he had patiently endured, he obtained the promise.

'For men verily swear by the greater: and an oath for confirmation is to them an end of all strife. Wherein God, willing more abundantly to shew unto the heirs of promise the immutability of his counsel, confirmed it by an oath: That by two immutable things, in which it was impossible for God to lie, we might have a strong consolation, who have fled for refuge to lay hold upon the hope set before us: Which hope we have as an anchor of the soul, both sure and stedfast, and which entereth into that within the veil; Whither the forerunner is for us entered, even Jesus, made an high priest for ever after the order of Melchisedec.'