"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”1

With “The Pulley” we return to the metaphysical conceit. Remember, a metaphysical conceit is an extended metaphor (which is what a conceit is) that uses some thing (often a physical object) to point through an unusual comparison to some spiritual, eternal, or transcendent idea (that’s the metaphysical part).

The first thing I will note about this poem is that the word “pulley” appears nowhere in it. (Sorry for the spoiler!) But if you are reading this poem for the first time, I think it is helpful to know that and to approach reading it by asking yourself, “Where is the pulley?” Or more specifically, “What is the pulley?”

The next point is to remind you of what we ought to always attend to in reading poetry: the stanza structure. Paying attention to stanzas generally means treating each stanza as almost a paragraph by considering what main idea is developed in that “paragraph” before moving on to the next. So for this week’s post, I will copy and read (for those of you who are listening) the poem one stanza at a time and pause to consider each one in turn.

When God at first made man,

Having a glass of blessings standing by,

“Let us,” said he, “pour on him all we can.

Let the world’s riches, which dispersèd lie,

Contract into a span.”

The poem opens on the event of God’s creation of humankind. “Let us,” God says (with Herbert’s nod to God’s trinitarian nature). God continues by expressing his will to grace humanity by pouring out all the blessings he can upon them. Herbert paints a picture of these blessings as being in a glass nearby. Isn’t this delightful? God has these blessings all at the ready, so abundant that they just pour out.

The poem then reminds us of the goodness of all God’s creation in noting that the entire world is filled with riches. And yet, human beings are distinct enough that God wants to contract (or condense) these riches within this special creation—this repository of blessings—man.

So strength first made a way;

Then beauty flowed, then wisdom, honour, pleasure.

When almost all was out, God made a stay,

Perceiving that, alone of all his treasure,

Rest in the bottom lay.

So the blessings thus flow: strength, beauty, wisdom, honor, pleasure. (By the way, these lines, like all in the poem, really, are very pleasurable to read aloud. Give it a try! Each word demands enunciation and contemplation and appreciation—as do all good blessings.) Just as the glass of blessings is almost poured out, God halts: “rest in the bottom lay.”

Now this is brilliant! What lay in the bottom? Rest: the rest or remainder of the blessings, of course. But also the blessing that is rest.

Why does God hold this blessing back? The next stanza explains:

“For if I should,” said he,

“Bestow this jewel also on my creature,

He would adore my gifts instead of me,

And rest in Nature, not the God of Nature;

So both should losers be.

If, God explains, he were to give humankind the blessing of rest, humans would worship God’s blessings instead of God, who is the source of blessings. We would “rest in Nature, not the God of Nature.” Now, there is potentially a whole theological treatise here in why it is that of all God’s blessings, it is rest in particular that the poet sees as one that would draw our worship away from God. I want to stop and wonder if any of the others might do so as well, but for now I don’t know. I do know that God sees rest as so important that he himself rested on the seventh day and that he builds rest into our rhythm of life and worship.

But here’s my favorite part of this stanza: the poem portrays God lamenting that if man were not to turn to God for rest, “both would losers be.” It’s not just that humans lose by not resting in God, but that God loses in not having us come to him. God desperately desires us to turn to him. (Of course, God isn’t “desperate” about anything, but you know what I mean—and, I hope, what Herbert means to communicate here about God’s desire to fellowship with his children.)

“Yet let him keep the rest,

But keep them with repining restlessness;

Let him be rich and weary, that at least,

If goodness lead him not, yet weariness

May toss him to my breast.”

So God withholds “rest,” while letting us keep “the rest” (isn’t language fun?), leaving us restless so that that restlessness will bring us to him. After all, we can’t count on our own goodness to bring us to God, which is a theologically significant point Herbert subtly but clearly includes.2

But here is my favorite part of the poem: Herbert depicts our return to God as a movement that is gentle, even maternal. It is not a thrusting but a tossing. It is not to his shoulder but to his breast that we return. (Again, I urge you to read this entire poem aloud, slowly, letting your mouth feel the words in a way that sends signals to your brain about their meaning. “May toss him to my breast” alone is filled with rhythm, alliteration, consonance that create the effect of being tossed from the tongue to the heart.)

Here we are at the end of the poem, and where is the pulley? You have probably figured it out by now, reader. What pulls us back to God?

Our restlessness.

As Augustine famously confessed, “Thou hast formed us for Thyself, and our hearts are restless till they find rest in Thee.”

NEXT UP (order may change at my whim):

“Jesu”

BOOK NOTE:

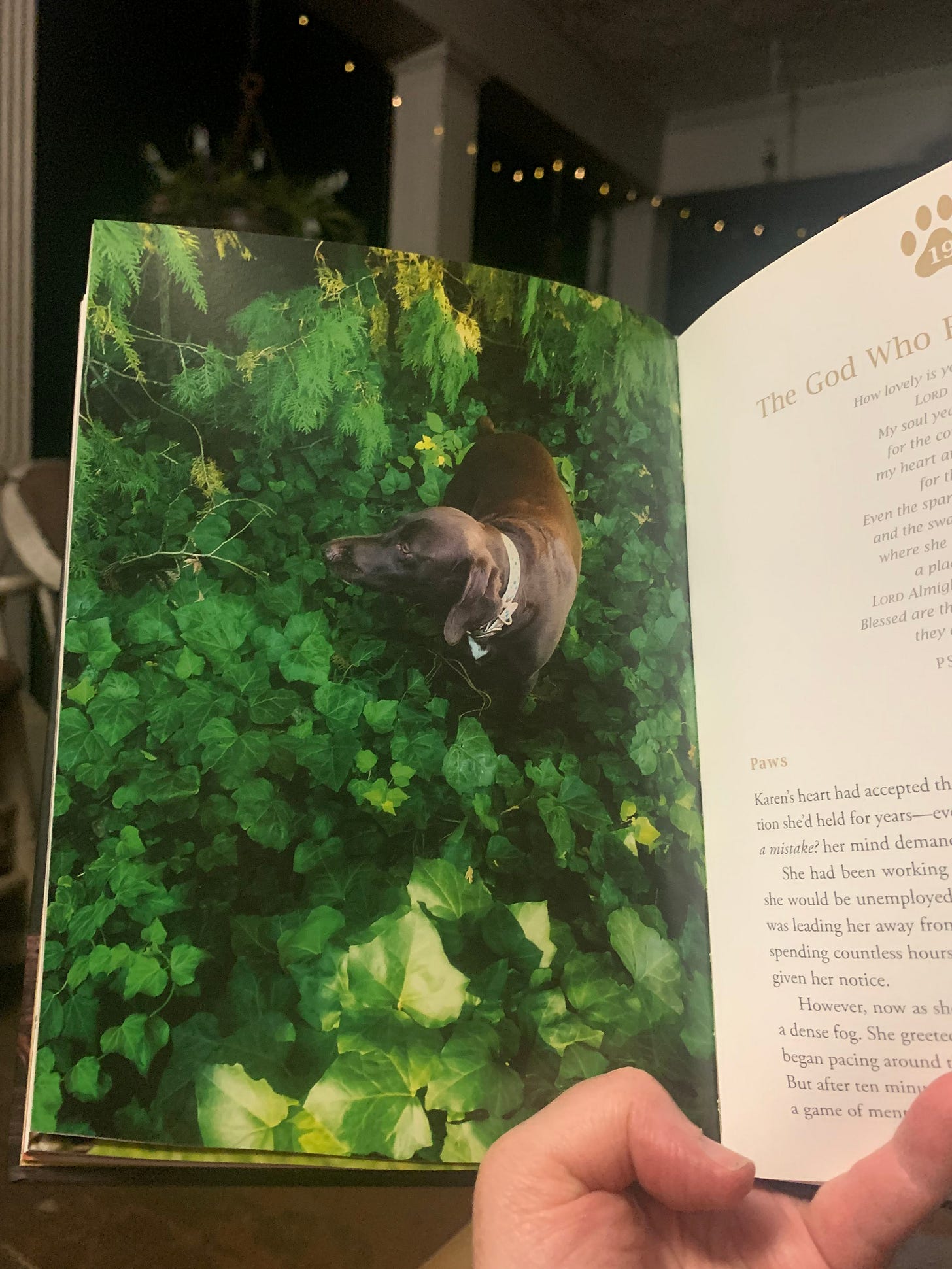

This week’s book is the newly-released Paws in His Presence: 50 Inspirational Animal Stories to Help You Pray and Ponder the Psalms by Jennifer Marshall Bleakley. To be clear, I’m a little bit biased toward this book because our dear Ruby appears in it! Jennifer draws on the story of Ruby being lost (which you can read here) and my own losses over the past year (which most of you know about, but you can read a bit about here and here). I’m thrilled to be part of such a thoughtful, beautiful collection of some of my favorite things.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

Whether or not Herbert was Calvinist, and if so, what kind of Calvinist, has received a good deal of critical attention. It’s interesting that the poem indicates that goodness might not (“if”) bring us back to God. And then, as I note, the language used to describe that return is gentle and maternal, not harsh and fiery the way some brands of Calvinists would have it.

"So BOTH should losers be" - isn't that an amazing, unexpected truth? Quite breathtaking. It makes me think of Paul's words to the Ephesians that he is praying for them to know (likely because like us they'd find it hard to believe) "the riches of his glorious inheritance in his holy people" - not riches he has for them, true as that is, but that they - we! - are HIS inheritance, rich and glorious. Herbert, again, is right on the money, both theologically and poetically.

Dear Karen, I listened to you read this post while I was driving today, and am anxious to get home and get my Herbert volume in front of me to read the poem. Hearing you remind us about the value of reading poems out loud so that the way the words sound in our mouths will send signals to our brain really resonated. Thank you again for inviting us all to your classroom.

(PS, how fun to have a story of Ruby in this upcoming book. Gosh I remember praying for her safe return all those years ago. How we rejoiced!)