"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”1

Correct me if I’m wrong, readers, but I suspect that George Herbert is a poet who is unknown and overlooked by many. I don’t believe I was introduced to Herbert in any of my own classes as a student, but only began to read and study him in the course of teaching British literature. Once I did, I marveled at what I had somehow missed.

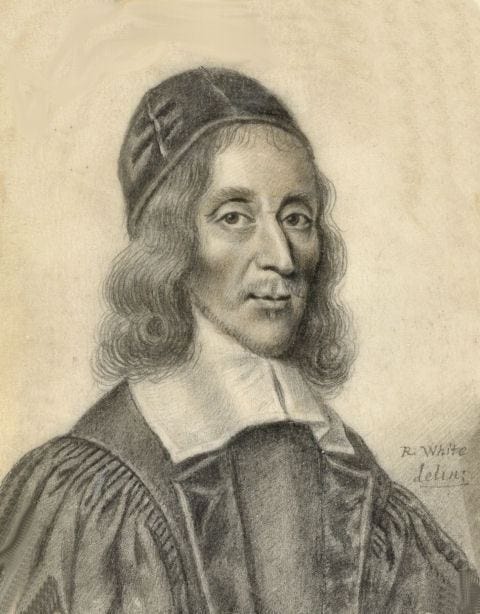

Herbert (1593-1633) was a contemporary of Shakespeare and John Donne. In fact, Herbert and Donne were friends, and despite some differences in their poetic subject and style, clearly influenced one another. Herbert attended Trinity College at Cambridge (I can’t believe I was just there!) and received a fellowship that allowed him to write poetry before being appointed as “public orator” for Cambridge and was elected to Parliament in 1624. He finally took holy orders, and in 1630—well into his thirties—began his pastoral ministry. He took a post in a country parish where, by all accounts, he served lovingly and faithfully before his life was cut short just three years later at age 39 following years of chronic illness.

We know much about Herbert’s life and temperament because of his poetry, of course, but also through his letters and a small guide he wrote for fellow clergymen (published posthumously in 1652) titled The Country Parson. Here he gives counsel for rural ministry, a calling so different from the aristocratic, politically-connected world that had been his life for so long. Here is a quote from The Country Parson in which Herbert talks about the place of mirth in the life and ministry of the rural pastor. (He covers all of the more expected topics, too, of course.) I’ve retained the older English because it is lovely. You can find the entire work here.

The Countrey Parson is generally sad, because hee knows nothing but the Crosse of Christ, his minde being defixed on it with those nailes wherewith his Master was: or if he have any leisure to look off from thence, he meets continually with two most sad spectacles. Sin, and Misery; God dishonoured every day, and man afflicted. Neverthelesse, he somtimes refresheth himselfe, as knowing that nature will not bear everlasting droopings, and that pleasantnesse of disposition is a great key to do good; not onely because all men shun the company of perpetuall severity, but also for that when they are in company, instructions seasoned with pleasantnesse, both enter sooner, and roote deeper. Wherefore he condescends to humane frailties both in himseife and others; and intermingles some mirth in his discourses occasionally, according to the pulse of the hearer.

Herbert’s surviving poems are found in a collection titled The Temple, which was published shortly after his death. The Temple is divided into three parts: “The Church-Porch” (an opening poem), The Church (the bulk of the text, containing 177 poems in a variety of forms), and a final concluding poem titled, “Church Militant.” We will consider in this brief series several (hopefully) representative reflections of Herbert’s wide range of poetic forms and styles. (I may have to add to the initial list as we go along. It’s so hard to choose!)

The Norton Anthology of English Literature describes Herbert’s poetry overall as “deceptively simple and graceful, especially compared to the learned, witty style of his friend John Donne.” I think that’s a helpful characterization, one good to keep in mind (even though the one we are starting with today is not his simplest). I also like the description given by the Poetry Foundation: “Herbert’s poetry, although often formally experimental, is always passionate, searching, and elegant.”

And it is that element of searching, I think, that is the recurring theme in many of Herbert’s poems. As the Norton Anthology (again) puts it, Herbert’s “primary emphasis is always on the soul’s inner architecture.” I think that is a lovely and accurate depiction. Herbert’s poems show him plumbing the depths of his faith, examining the state of his heart, and seeking to know and trust Christ more. I also like how this webpage devoted to Herbert’s life in Bemerton, home of his country church, describes him:

In common with most of us, George Herbert struggled for most of his life with conflicting desires. On the one hand, he was a gifted scholar who shone at school and university and for whom a glittering political career seemed to beckon. On the other, guided by his mother, he was conscious of a constant leaning towards a calling to ordination as a priest. This persistent inner turmoil was the source and inspiration of much of his poetry.

I chose “The Collar” to begin this series for a couple of reasons. First, it is a metaphysical poem. (Readers, if we were together in class, I’d quiz you on that right now. But since we’re not, you can go back and look at the posts on John Donne to brush up!) But Herbert’s metaphysical approach, while brilliant and evocative, tends to be gentler, more personal, and more earnest than Donne’s witty and cerebral style. In “The Collar” we will find a metaphysical conceit: an ordinary, physical object (a collar) pointing toward eternal, spiritual things. And yet “The Collar” is also deeply personal and searching. Not just a witty exercise, it is also an earnest prayer.

The other reason I chose this poem to begin with is that it is fresh on my mind since I include it in my forthcoming book on calling and vocation—and that’s what this poem is about. (So you get kind of a sneak peek of my new book that comes out next year!) The fact is that calling is the subject of many of Herbert’s poems. “The Collar” is about Herbert’s call to wear the clerical collar.2

But even more than that, this poem is his expression of lamentation and frustration to God—and his ultimate faith in God despite so many hard disappointments.

Knowing these two main points offers the best way, I think, to approach this poem. I will add a few more notes here and then end with the poem itself. It’s one of those works which—once reading it—leaves little to say, at least at first. So let me draw your attention then to a couple more things.

Notice that nearly the entirety of the poem is in quotation marks. All but the first half line and the last few lines are one long monologue offered by the speaker to—we figure out eventually—God. It is God who is the “thou” and “thy” referenced by the speaker. It is God who is the object of this violent outburst, one preceded, in fact, by a fist slammed onto the table (or board). This hammering fist—the scene visualized and heard—is key to hearing the tone in which this expostulation is offered. It suggests anger, frustration, and, slowly, loss and bewilderment as the speaker (who is assuredly reflecting the state of Herbert’s own soul) declares his intention to quit the ministry, give up the collar, and do something more fruitful with his life. He even blames God—the God who could bring forth fruit in his ministry but doesn’t, whose thoughts are “petty,” who winks and does not see. Whoever serves a God like this, the rant concludes, deserves what he gets. What an idiot and fool he must be!

So he raves and raves.

Until he hears the Lord saying softly, “Child.”

And the minister responds, “My Lord.”

Note that the first word of the poem is “I.” The last word is “Lord.” In between is one long expression of heartfelt pain, anguish, anger and despair, spoken to God about God. And all that dissolves with one loving word from God: “Child.”

I struck the board, and cried, "No more;

I will abroad!

What? shall I ever sigh and pine?

My lines and life are free, free as the road,

Loose as the wind, as large as store.

Shall I be still in suit?

Have I no harvest but a thorn

To let me blood, and not restore

What I have lost with cordial fruit?

Sure there was wine

Before my sighs did dry it; there was corn

Before my tears did drown it.

Is the year only lost to me?

Have I no bays to crown it,

No flowers, no garlands gay? All blasted?

All wasted?

Not so, my heart; but there is fruit,

And thou hast hands.

Recover all thy sigh-blown age

On double pleasures: leave thy cold dispute

Of what is fit and not. Forsake thy cage,

Thy rope of sands,

Which petty thoughts have made, and made to thee

Good cable, to enforce and draw,

And be thy law,

While thou didst wink and wouldst not see.

Away! take heed;

I will abroad.

Call in thy death's-head there; tie up thy fears;

He that forbears

To suit and serve his need

Deserves his load."

But as I raved and grew more fierce and wild

At every word,

Methought I heard one calling, Child!

And I replied My Lord.

NEXT UP (order may change at my whim):

BOOK NOTE:

It’s been a joy to interact over the past year or so with the Blackaby family. Years ago, like many Christians, I was influenced by the work of the family patriarch Henry Blackaby through his famous Bible study, Experiencing God. After years of fruitful ministry, Henry died just earlier this year. Last year, Blackaby Ministries hosted what turned out to be a lively conversation with me, which you can view or listen to here. Recently, Mike Blackaby and Daniel Blackaby published a book that it was my honor to endorse: Straight to the Heart: Communicating the Gospel in an Emotionally Driven Culture (David C. Cook). This seems a fitting book to present when we are beginning a study of George Herbert, for the book is a guide (for pastors and others) to communicating the Christian faith in ways that reflect the heart of our times: through story, beauty, art, desire, and community.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

The Norton Anthology footnote for this poem also points out that “collar” also suggests the slave’s collar (as the speaker feels the clerical collar has become that) and that it also is a pun on the word “choler” which refers to his anger. Perhaps most importantly, the poem ends with another pun: God as Caller.

Also, isn’t that a great collar Herbert is wearing in his portrait above?

I’ve been thinking about this poem all week. Your comments, friends, have been so rich. My attention was just drawn to these lines, lines that really must be read and heard *just right* I think to really get:

Have I no harvest but a thorn

To let me blood, and not restore

What I have lost with cordial fruit?

Let me paraphrase this passage a bit because I think it contains so much.

It’s asking/saying: Do I have no harvest but a thorn that draws my blood and does not restore that blood with any fruit?

And here”cordial” refers also to wine … Christ’s blood. Herbert sees no fruit from this thorny vine. He also does not see the restoration of his suffering and labor with Christ’s blood.

By the end, he’s come to his senses, but here he is questioning it and questioning everything.

So powerful. So real.

Just, wow - what an intense and intensely honest and vivid expression of the conflict inherent, it seems, in all calling. Such wrestling. And to conclude it with an apparent allusion to the calling of Samuel which reads so mild by comparison is very affecting.

In his book, Music After Midnight: The Life and Poetry of George Herbert, John Drury observes that "‘The Altar’ and ‘Easter-wings’ ... are shaped and physically formed like their subjects. Those poems, however, make shapes to fit order. The marvel of ‘The Collar’ is that it makes a shape to fit disorder. There was, perhaps, nothing like that again until T. S. Eliot wrote The Waste Land." He also quotes Herbert's brother Edward saying of his sibling, ‘he was not exempt from passion and choler' and comments that "The Herberts were an inflammable lot. ‘Choler’ sounds just like ‘Collar’..."