[Gerrit Dou, “The Prayer of the Spinner” Public Domain https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15494955]

“Prayer (I)” is probably one of Herbert’s most known and most loved poems. And for good reason. (Note: Herbert titled several poems “Prayer,” which is why they are also numbered. If you’ve been here a while, you may recall that I wrote about “Prayer (III)” in one of my early posts here at The Priory.)

As a poem, “Prayer (1)” is both simple and complex. It consists of a series of metaphors for prayer. The poem doesn’t have even one grammatical sentence, but rather just this long list of metaphors.

That is not to say the poem has no structure. It is, in fact, a sonnet, one that uses the unusual rhyme scheme of ABABCDCDEFFEGG. Each item in the list is likened to prayer. Moreover, some of the metaphors are separated by commas, some by semicolons. I take those separated by semicolons to be separate items and those by commas to be connected in some way—perhaps. But I think it’s open to interpretation.

These metaphors characterize prayer in so many evocative ways that once encountering this poem, I don’t think one can see prayer—or those things likened to prayer—the same way ever again.

I commend for your listening joy this reading by Iain McGilchrist, a philosopher and psychiatrist most known these days for his provocative writing on the mind. (I’ve read a little of his work and it is fascinating and helpful for a skeptical age.)

I’ve taught this poem in the classroom countless times, and when I have done so, it has been more like praying than teaching as we simply contemplate and elucidate the power and effect of Herbert’s metaphors—both singly and cumulatively.

Let’s read the poem now, and then do the same—contemplate and elucidate. I shall go first (below) by offering my own impressionistic and associative responses, paraphrasing or explicating the metaphors as they move me.

I hope you, readers, will add your own impressions and illuminations in the comments.

Prayer, the church's banquet, angel's age,

God's breath in man returning to his birth,

The soul in paraphrase, heart in pilgrimage,

The Christian plummet sounding heav'n and earth;

Engine against th' Almighty, sinner's tow'r,

Reversed thunder, Christ-side-piercing spear,

The six-days world transposing in an hour,

A kind of tune, which all things hear and fear;

Softness, and peace, and joy, and love, and bliss,

Exalted manna, gladness of the best,

Heaven in ordinary, man well drest,

The milky way, the bird of Paradise,

Church-bells beyond the stars heard, the soul's blood,

The land of spices; something understood.

The poem opens with church imagery, which is most appropriate. It seems we are in for a more conventional ride than the one we will be taken on. “Church” and “banquet” are expected metaphors for a subject so central to the Christian life—prayer. Eating, feasting, and banquets are prevalent throughout the Bible. Even so, painting prayer as a feast is inviting and evocative. A feast or banquet suggests plenitude and company, variety and fellowship. I think of how important prayer support is from fellow believers, whether it is in seeking prayer for a health crisis, a lost dog, or some material need. If prayer is an “angel’s age” then it is immortal, yes? It is the breath of immortal God in us. It is the very soul expressed in words (albeit in a loose translation). “Heart in pilgrimage”—this can hardly be expressed any better or explained any further. Like many of the metaphors in this poem, it is perfect and complete. The “plummet” refers to the fall of humankind, a fall that necessitated Christ’s coming to earth to redeem us, making that fall, in the end, a happy or fortunate one, because in Christ’s work, God is glorified—and heaven resounds. This first stanza is filled with conventional Christian imagery—put to unconventional use.

The next stanza takes a strange—mechanical—turn. Prayer is an engine? An engine that works against the Almighty? Perhaps this image conveys the idea that prayer expresses a sinner’s will and wishes, and these may be will and wishes that are not God’s. Yet, he hears them anyway. They reach for him like a tower, perhaps even the Tower of Babel. While thunder rolls down from heaven to earth where we hear it and tremble, prayer rolls up from us to God’s ear (and he does not tremble). Prayer is powerful. Reversed thunder indeed. (This is one of my favorite images of prayer from the poem but it is hard to choose!) Prayer is a spear that goes through the side of Christ? Christ feels and bears and bleeds out our petitions to God. Prayer is music rendered at a tempo that contains all of creation in one score and is heard by all of creation.

Prayer is what my yoga teachers aim for: softness, peace, joy, love, bliss. God gave the daily bread of manna that covered the ground, and prayer is the daily bread we lift up to him by trusting him, asking him, and giving thanks to him. Daily. It is good when a good man or woman is glad (bad when a bad one is). In the church calendar, ordinary time constitutes most of the year—they are the days and weeks between the major seasons. These times, the non-holidays, the non-feast days are heavenly, too. For the kingdom of God is already at hand. Prayer reminds us of this. The ordinary is of heaven. So, too, are the extraordinary wonders: the sky adorned with stars, birds adorned with feathers, people decked out in fine clothes.

The couplet impresses me on how prayer involves all the senses: ears that hear church bells ring, eyes that see stars in the galaxies, movement we experience from inside when body and soul feel alive, the taste and smell of all spices that fill the earth. Through these senses and through the sense made possible by the human mind——we can, miracle of miracles, understand.

Amen.

NEXT UP (order may change at my whim):

BOOK NOTE:

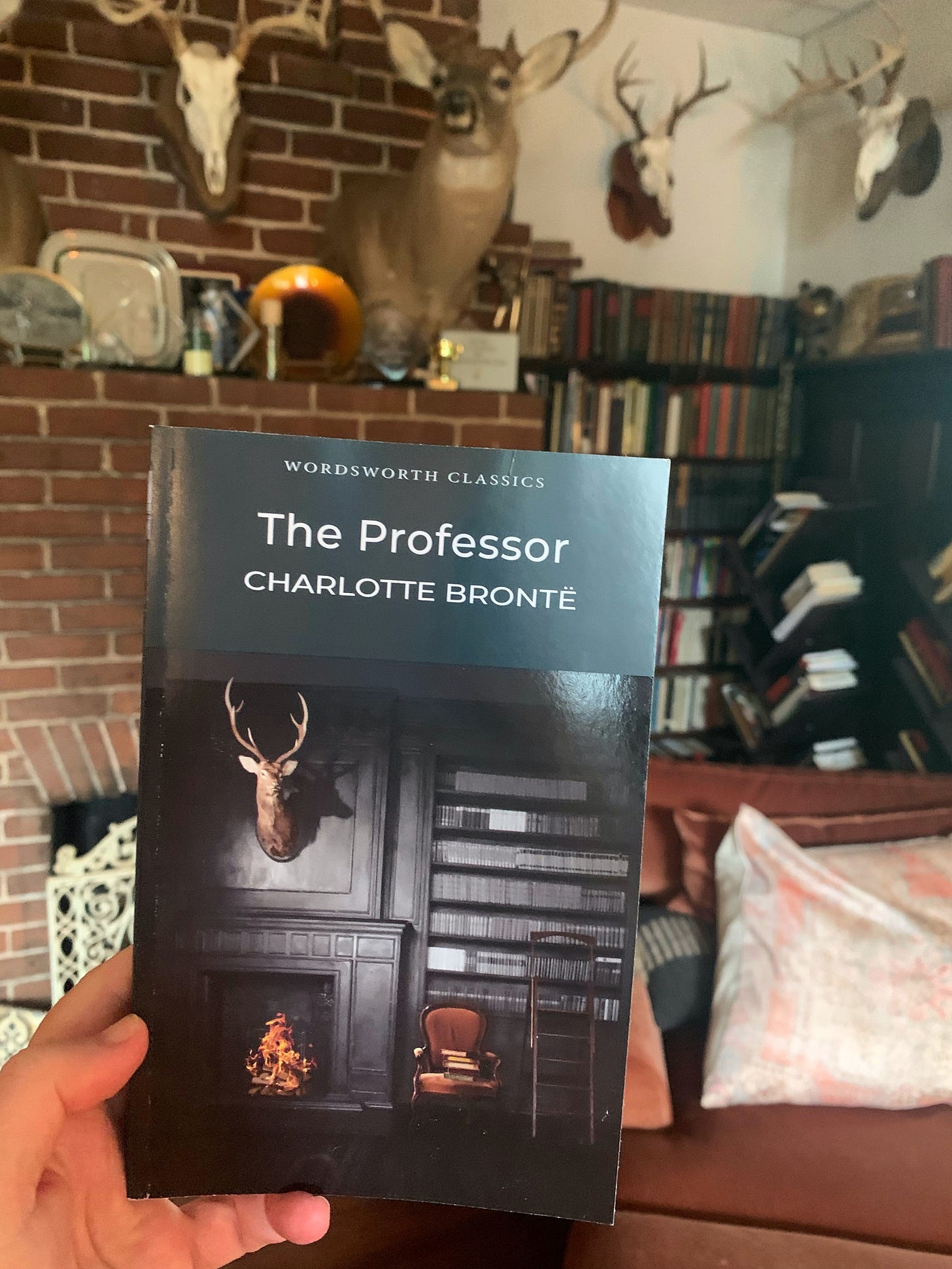

This week’s book is presented in tribute to The Priory’s beloved Holly, a gentle reader personified. She shared some of her beloved books in a recent post, and that post reminded me that I have not yet read Charlotte Brontë’s novel, The Professor. So I immediately bought a copy, picking an edition based on the cover alone because, really, why would I not get the one depicting a room that is so similar to my favorite room in my house (as you can see). It’s lightweight and therefore perfect for some travel I have coming up. I will report back at some point!

ONE ADDITIONAL NOTE:

I’ve seen lots of chatter on Substack lately from writers trying to figure out whether to quit or offer only paid posts or more paid posts, etc. As more and more writers join the platform, I am ever more grateful to have a good group of you willing to support my writing in this space. (It is my dream that someday this will be the place that Twitter once was, so keep joining!) Some of you have been doing this from the start, over a year ago. Some of you are new supporters. I’m thankful for all of you. It is my desire to continue offering my “classes” here for free for the foreseeable future. Every one of you who supports me makes that possible. And if you are not yet doing so and want to contribute to this little gift I’m offering to the world (I hope it’s a gift, haha!), I would truly be grateful. If not, a free subscription is also a hugely helpful way to support my work, too. :)

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”1

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

Herbert's poem is itself a banquet, so many rivers of thought emptying into the one ocean. I love it dearly. Each line can be lived with (and in) for a long time but I find I'm most often taken with how he chooses to close the poem with what feels like the most prosaic phrase in the whole: prayer is "something understood". By whom, George? By God himself? He knows what these apparently random, half-formed utterances mean? That's so hopeful. By me?? I fear not. It remains elusive.

Re plummet - I think I've always read that as a noun rather than a verb, having in mind the plumbline that determines (sounds) how deep the sea is, so prayer tries to comprehend the depths of heaven and earth. Perhaps Herbert intends both noun and verb?

Malcolm Guite has a collection of 27 sonnets that take this poem phrase by phrase and develop its thoughts. It's a wonderful collection (it's in a book titled 'After Prayer'). Highly recommended.

Thank you, Karen.. I hope you enjoy it.

The engine I thought of is an ancient one, the seige engine, conveying the idea of besieging God in heaven with one's petitions. It connects in my mind with Jacob wrestling God, saying "I will not let thee go, except thou bless me." Or Job, pleading in chapter after chapter with God as in a court of law to answer Job's case. Or Jesus, telling us to pray and not to faint.

Herbert's poetry is in a style that I associated with modern poetry - creating shapes from words, or like this Prayer, composing an entire poem from multiple different short metaphors. When I took a course in writing, they talked about such modern poetic techniques and never mentioned Hebert, yet he was the real innovator.