1[Photo of Windhover By Andreas Trepte - Own work, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5024397]

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.” – Simone Weil[1]

(Note: if you’re new here, first, welcome! Second, I invite you to read my very first newsletter. It not only introduces me but also introduces my current situation which produced The Priory. Weekly newsletters are free, but a paid subscription helps support all the other work I do—and lets you join this community in the comments.)

* * *

Today a new book releases that I had a hand in making. (Yes, I’ve been busy!) This book is a new edition of a classic work by Eugene Peterson, his study of Galatians, Traveling Light, newly re-issued by InterVarsity Press. I’ve written the foreword. (See the end of this post for details of a giveaway.)

I can’t reproduce the short foreword here (although I can encourage you to get the book or encourage your library to do so). But I will share a bit of what I include in it.

If you know anything about Eugene Peterson, you know that he loved the poetry of the nineteenth century British poet, Gerard Manley Hopkins. I love Hopkins, too. No, I adore Hopkins.

In the foreword to Traveling Light, I include one of Hopkins’ most beautiful poems and a bit of commentary on how the poem connects with Peterson’s study of Galatians and the theme of freedom in Christ that Peterson finds in that New Testament letter.

When IVP approached me about writing the foreword for this book, I wasn’t entirely sure I wanted to. I had to read the book first! That decided it. However, when I was digging in to the text more deeply in order to attempt a proper introduction to this rich work, I realized that I needed to study Galatians and Peterson’s words about this biblical text. I told my editor when I turned the foreword, “This was a piece I didn’t even know I needed to write, but I did.”

The Hopkins poem I include in the foreword is “The Windhover” (1918). The poem describes the speaker catching sight of this majestic bird, one he describes, paradoxically, as both “morning’s minion” and “kingdom of daylight’s dauphin.” (A minion is an underling while a dauphin is the title of a royal heir-apparent. Kind of like being human and divine … ) The bird’s exhilarating sweeping and swooping—both free and controlled, in the way of a skilled chevalier (or knight)—points the speaker to Christ and to the speaker’s need for him: “My heart in hiding stirred for a bird.” (Goodness! What a beautiful rhyme!) Like the riding bird, Christ is a knight, a warrior whose wound brings forth blood that is not merely red (and mortal) but gold (and eternal).

As with all of Hopkins’ poetry, this is a poem to be read aloud, read over and over, read for sound and sight as much as sense. It is as luxurious in its word play as it is in its theme on the most divine creation and the Creator.

The Windhover

I caught this morning morning's minion, king-

dom of daylight's dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing

In his ecstasy! then off, off forth on swing,

As a skate's heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: the hurl and gliding

Rebuffed the big wind. My heart in hiding

Stirred for a bird,—the achieve of; the mastery of the thing!

Brute beauty and valour and act, oh, air, pride, plume, here

Buckle! AND the fire that breaks from thee then, a billion

Times told lovelier, more dangerous, O my chevalier!

No wonder of it: shéer plód makes plough down sillion

Shine, and blue-bleak embers, ah my dear,

Fall, gall themselves, and gash gold-vermillion.[i]

It is Gerard Manley Hopkins who brought me to Eugene Peterson.

I’ve only come to know the work of Peterson a little in recent years, and the more I’ve read, the more I’ve realized what I’ve been missing out on for a long time.

I’ve also had a good chuckle at God’s keen sense of humor.

You see, I remember, when Eugene Peterson’s paraphrase of the Bible, The Message, written in “contemporary English” was completed in 2002, I snickered a bit with friends. “The Massage,” we called it, with knowing superiority. We were intellectuals. We were academics. We were serious Christians. We liked our Bibles to be translated, not paraphrased, and the more formally equivalent the better.

I’m still an academic. I’m still a serious Christian. But intellectual? Hmmm.

I’m reminded of the meaning of the word “sophomore,” which means “wise fool.” It’s not the first-year student who is such, nor the upperclass student, but the one with a smidgen of knowledge who raises the kind of caution offered famously by Alexander Pope in these lines from his brilliant poem, An Essay on Criticism (1711):

A little learning is a dang'rous thing;

Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring:

There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,

And drinking largely sobers us again.[ii]

Essentially, Pope predicted the Dunning-Kruger effect,[iii] the finding that the incompetent tend to overestimate their competence while the competent tend to underestimate theirs. “Wise fool,” indeed.

I’ve changed my mind about paraphrases of the Bible (and some translations, too). Different texts, different renderings, even different translations fulfill different purposes. Don’t get me wrong: as a longtime student of language, I prefer close translations to paraphrases. But only if we understand the telos of a thing can we even begin to judge its excellence. A paraphrase has a certain purpose, just as a close translation does.

Besides, all of this human life is a paraphrase, isn’t it? Human life, as real as it is here and now, is also a semblance of the one who made us and a foreshadowing of what is to come. Yet, it is still full of meaning, a striving to communicate the essences of ourselves and all we experience and understand.

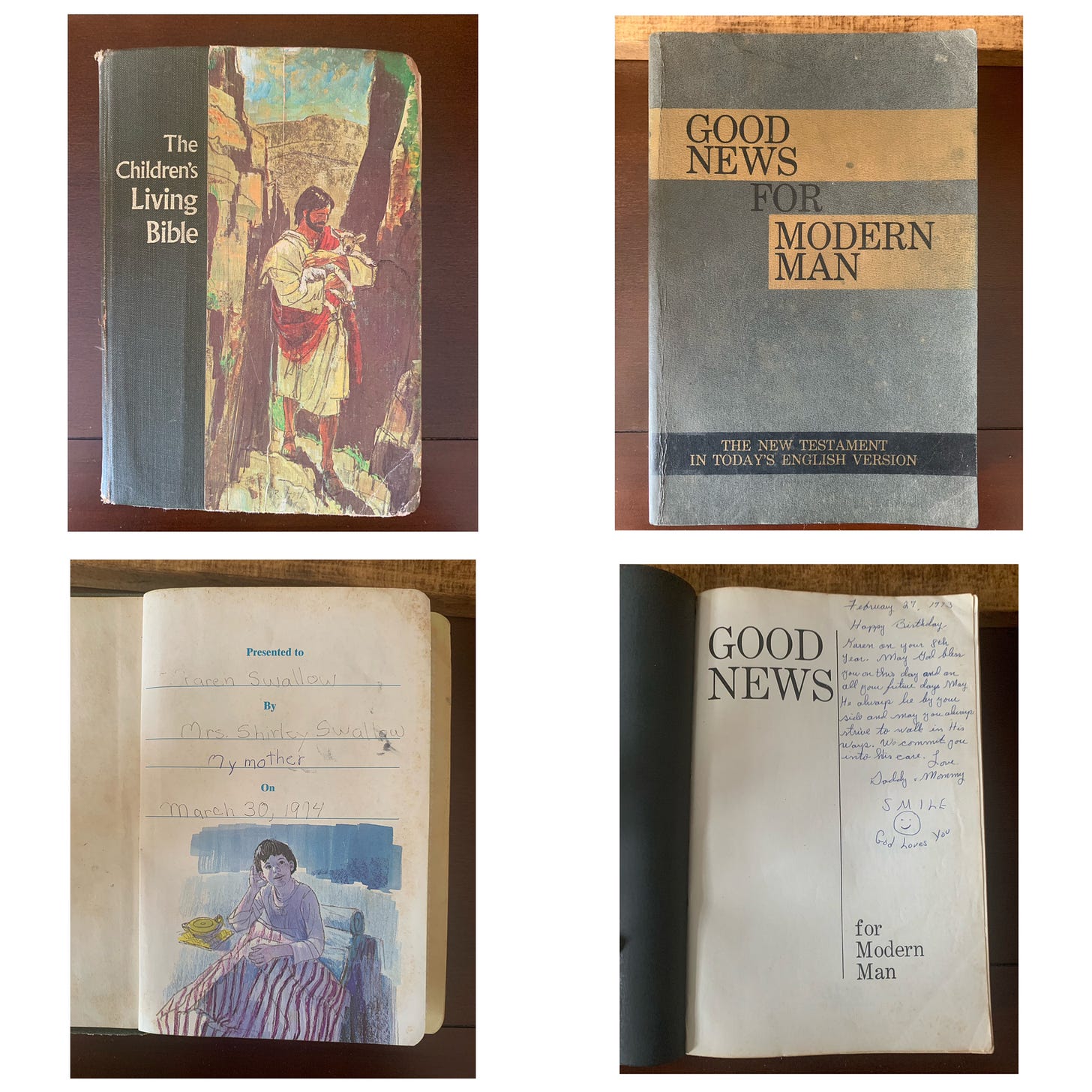

My first “real” Bible as a child was The Children’s Living Bible, a paraphrase. The parents who raised me in the faith also gave those scriptures to me when I was yet young, and that Bible helped me to grow and to remain in the faith. I’ve had (and have) countless versions of the Bible since then. They are all precious. None of their words will return void (even if I prefer some of their words more than others).

[A photo taken by me of the two Bibles my parents gave me as child. I still have them.]

The thing I’ve learned over the years is that language is most powerful when it’s playful. Precision is extremely important, too, of course. But how do we know what we mean unless we have a menu of words from which to choose? And how do we choose the best, right word without an array of possibilities? How do we find the fixed Truth without the dance of Grace?

I once was a child.

Then when I grew up, I thought I was superior, educated, and smart.

Now, I just want to keep learning—like a child.

And to be free—in Christ.

****

*NEW DISCOUNT GROUP SUBSCRIPTION PRICE: I’m still figuring out how this Substack thing works. Now groups of two or more paid subscribers receive 20% off each subscription. Paid subscribers are able to comment on posts (this allows me to keep the trolls away). I hope this helps more of you to join the conversation!

*BOOK GIVEAWAY: Restack this newsletter and I will choose one restacker over the next few days to receive a copy of Traveling Light.

[i] https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44402/the-windhover

[ii] https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69379/an-essay-on-criticism

[iii] https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/dunning-kruger-effect

What are other favorites of Peterson any of you have and why? I need to choose more of him to read.

Eugene Peterson's body of work has richly blessed my life and teaching, especially "A Long Obedience in the Same Direction" (on the Psalms of Ascent) and "Eat This Book" (on the necessity of meditation on the Word). I believe several of his book titles are drawn from Hopkins' poems.