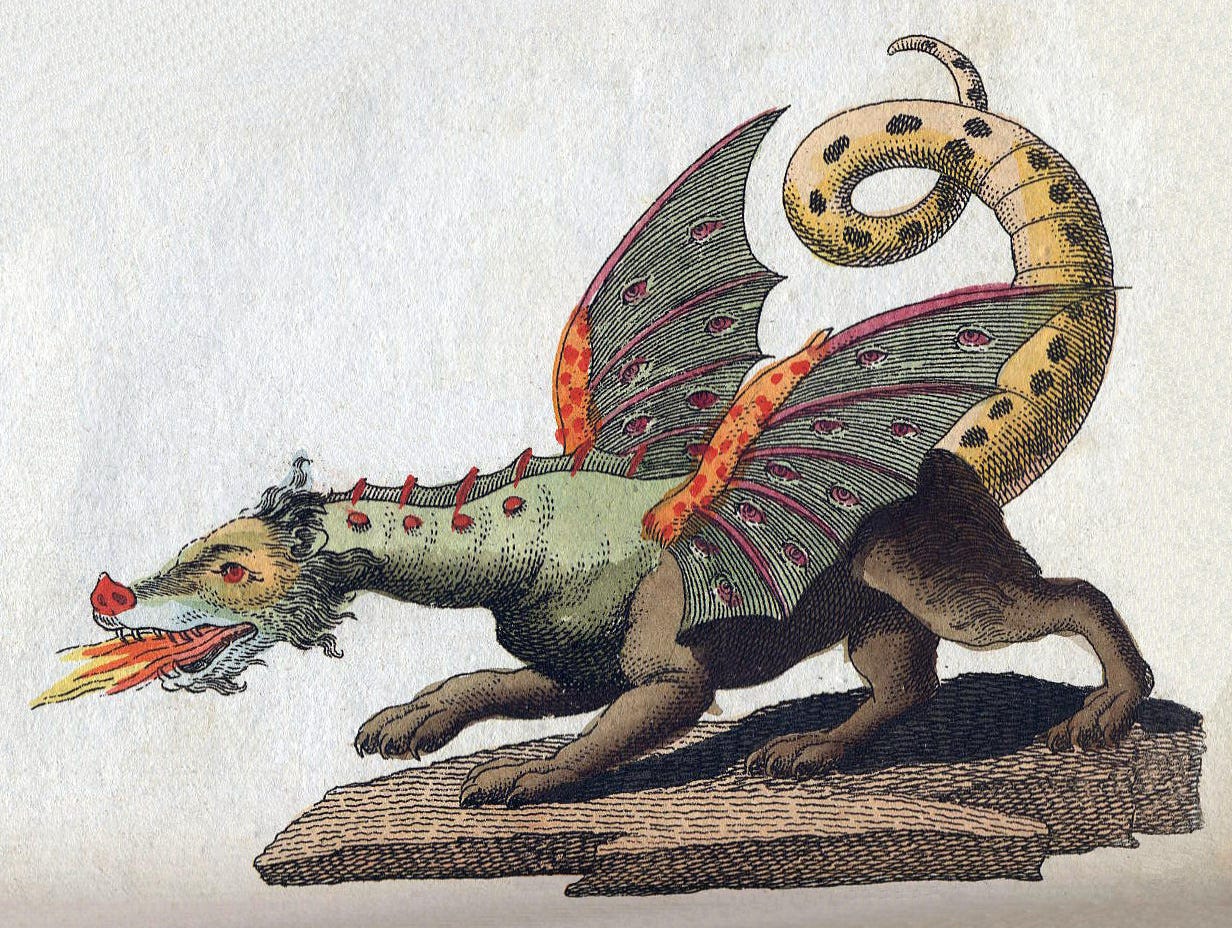

[Friedrich Johann Justin Bertuch, the mythical creature dragon, 1806, public domain]

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.” – Simone Weil1

I closed my first post about Beowulf by quoting J. R. R. Tolkien’s famous assessment that most of the lines in the poem constitute a “prelude to a dirge.”2 In other words, the work in it entirety is a lament, an elegy. All that comes before the mournful death, burning, and burial of the hero is the lead-up to the eulogy.

But what a eulogy.

And what a lead-up!

Each of the three battles narrated in the poem gets increasingly difficult for the hero.

Beowulf defeats Grendel alone, using no weapons, just the strength of his hands. Then, in battling Grendel’s mother, Beowulf first tries to use Hrunting, the sword loaned to him by his “frenemy,” Unferth. But the weapon fails. So Grendel resorts to his old method of hand-to-hand combat. But this monster outpowers him. He is only able to overcome this mad mother by using a magical sword he discovers in the monster’s underwater lair. Beowulf’s last battle, more than 50 years later, is his most protracted and difficult and, as it turns out, fatal.

This escalation of struggles contributes to the story’s drama, of course.

But another way of looking at this series of struggles is to consider the motivations, or the particular sins, of Beowulf’s opponents. Grendel, alien and outcast, is driven by envy that turns to hatred and malice toward people who’ve done him no harm. Grendel’s mother is fueled by vengeance against those who have done her great harm by killing her offspring. The dragon is “moved … to wrath” (line 2222) at the theft of a goblet from his hoard of treasure. Yet even before succumbing to the deadly sin of wrath, the dragon has clearly given in to greed.

Dragons can represent a great deal in stories, myths, and even the Bible. Yes, Virginia, there are dragons in the Bible. In fact, you can check out this fascinating podcast series on dragons in the Bible at The Bible Project. They say a lot in this series, but in sum, whatever dragons are or whatever they represent, they can be considered “creatures of chaos” who, in a variety of ways (whether as serpents in the garden or as evil spirits who tempt us), seek our harm rather than our good. The dragon in Beowulf certainly is such a creature.

Like the stereotypical dragon of mythical stories, this dragon’s drama centers around his horde of treasure. But it’s important to see how gold, jewels, gifts, and giving are prominent throughout Beowulf if we are to understand the significance of the dragon’s treasure trove.

The first king mentioned in the poem, Shield, founder of the Danish line, is described with the kenning “ring-giver” (line 36). Indeed, it was the duty of a good king to give gifts as a reward for loyalty and bravery. Thus, Hrothgar, called “the gray-haired treasure-giver” (line 607), bestows gifts abundantly upon Beowulf for his defeat of Grendel. In contrast to this good king, Hrothgar tells a story to those gathered in Heorot following Beowulf’s defeat of Grendel the story of a bad king, Heremod, whose life and reign spiraled downward after “giving no more rings / to honor the Danes” (lines 1719-20).

Furthermore, even in a pagan heroic poem in which women seem, at times, to be relegated too much to the background (sigh), women also take part in this gift economy. Hrothgar’s queen, Wealhtheow, “adorned in her gold” and “decked out in her rings,” graciously offers a goblet to all assembled, of all ranks (lines 612-19). And upon returning to his own homeland, Beowulf gives to his own queen the torque given to him by the Danish queen. (And many other gifts are given and received—exchanges accompanied by stories that give them even greater meaning—upon Beowulf’s return.)

Following the death of King Hygelac (whom scholars believe to be a historical figure), Beowulf becomes king of Geatland. “He ruled it well / for fifty winters, grew old and wise / as warden of the land“ (lines 2208-10). Later, Wiglaf reports after Beowulf’s death that his slain lord had also been a generous giver of gifts to his people (lines 2864-70). But wisdom is Beowulf’s greatest treasure.

In his wisdom, Beowulf senses his death “hovered near” (line 2421) in facing the dragon. But he fights anyway. He is not only wise, but courageous, too.

The dragon, on the other hand, embodies a spirit that is the opposite of magnanimity, generosity, and gift-giving. Of course, he’s a dragon—he’s supposed to be this way!

Yet, it is striking that the story goes out of its way to explain that the one who broke into the dragon’s lair and stole away the jeweled goblet did so, not out of greed or malice, but out of need:

It was desperation on the part of a slave

fleeing the heavy hand of some master,

guilt-ridden and on the run,

going to ground. (lines 2223-25)

Such empathy and compassion on the part of the Christian narrator of this old story from a pagan heroic warrior culture is essential to understanding and appreciating this work. Indeed, this understanding is one of the poem’s treasures.

When Beowulf, having been mortally wounded by the dragon, wishes to see the treasure he and his one loyal warrior have won (the others having fled), it is not out of selfish gain. Rather, Beowulf can take comfort in knowing that even in death he has provided for his people.

That was a good king.

Beowulf’s remains from the funeral pyre in which he was burned are buried by his people with precious jewels and treasure, as befits a good king.

Yet, the poet notes, such “gold under gravel, gone to earth” is “as useless to men now as it ever was” (lines 3167-68).

More lasting than gold are the memories and testimonies of those who were witnesses like the twelve (ahem, twelve!) warriors who rode around Beowulf’s tomb, expressing their sorrow, extolling their late king, giving thanks for his greatness, carving his legacy into lines of poetry that will never pass away on this side of the new heaven and the new earth.

I think Tolkien is right that Beowulf is ultimately a dirge. The narrative, as exciting and adventurous as it can be in places, is not entirely linear or straightforward. It is filled with songs and memories and re-tellings of things past. It is, at times, like a memorial service in which people are invited to share their stories, whether funny or sad, about the deceased. In this case, the deceased isn’t just Beowulf, but a time, a culture, and a place that existed long before this poem was written down—and long, long before you and I read it.

What poem are we writing with our lives that others will read years or even centuries later?

NEXT READING: As I said before, there is no syllabus for this little course of mine. (But, there also are no tests or papers! Hooray!) In two weeks, we will start The Canterbury Tales! Again, I’m not sure how many posts I will make, but we will start with The General Prologue and see how it goes. Here is an online version that includes the text in both Middle and Modern English.

NEXT WEEK: We will have a little “fall break” from the British Literature “class,” and I will share an issue I’ve been processing that’s more personal—and personal to a lot of other people, too. It will be heavy. Thanks for being here to share the heavy burdens with me as well as the lightness of love of all things literary.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

J. R. R. Tolkien, Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics https://jenniferjsnow.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/11790039-jrr-tolkien-beowulf-the-monsters-and-the-critics.pdf

Fascinated to read about dragons here this morning as I'm doing a brief prayer-meeting talk on Ps.87 this evening - where we hear of Rahab (not of Joshua's day, different Hebrew spelling). The sea-monster, the dragon Rahab of Ps.89, Is.51. Commonly seen as a figure for Egypt, in Ps.87, along with current bogey-man Babylon, Rahab the Dragon is recorded among those who will acknowledge the LORD and be deemed to have been born in Zion. Who'd have thought it?! Even 'dragons' can be redeemed. Those who have sought our harm and hurled chaos across our days becoming part of why glorious things can and will be spoken of the city of God. Colour me astonished.

There is a lovely paragraph in Tolkien’s commentary on Beowulf. “He may earn glory by his deeds, but they are all in fact done as a service to others. His first great deed is the overcoming of a monster, that had brought untold misery on Hrothgar and his people: Grendel, a “feond mancynnes.” His other deeds are done as a service to his king and his people: he dies in their defence. Beowulf does not come first with Beowulf. He’s loyal, even to his own disadvantage.” (p274)

I think this is why I love the ancient tale of Beowulf. After deciphering the old words, sorting out an ancient culture, and remaining rather unsure of the mythology, Beowulf comes shining through. He is a true hero, selfless and brave. Beowulf and his thrilling adventures are worth the work.