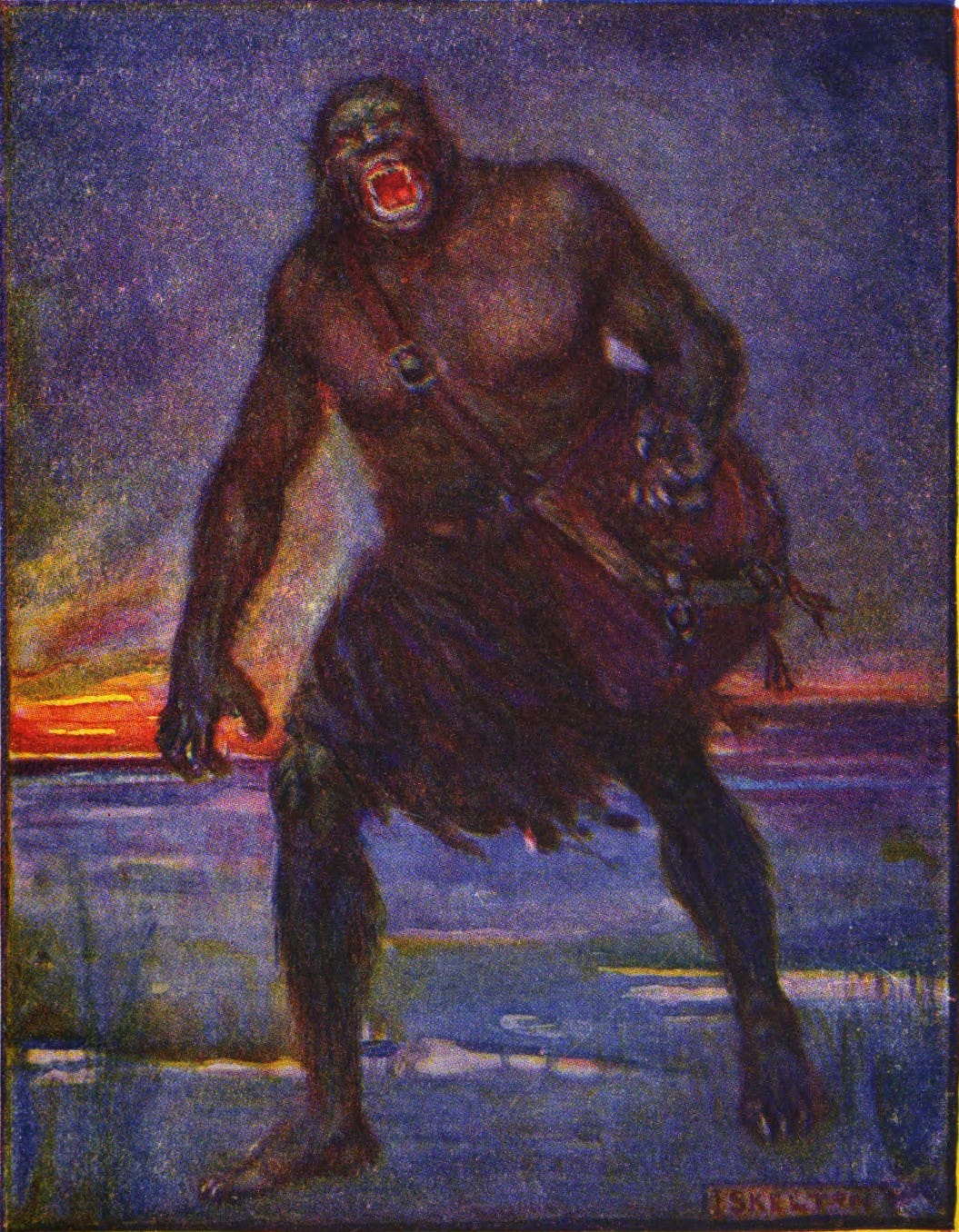

[An illustration of Grendel by J. R. Skelton from the 1908 Stories of Beowulf. (Public Domain)]

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.” – Simone Weil1

Dear readers, one month ago, The Evangelical Imagination released officially into the world! It has been a very busy time, in writing the book (obviously), but also in doing all the interviews, podcasts, and other conversations around the book. There have been a lot! If you missed any—or just want to catch one—you can find a list at this link. All of the interviews were so different and, to me, so interesting, as each host had different things to say. I hope you will check one or two out.

Now, back to Beowulf …

Last week, I addressed some aspects of the form of Beowulf. It is impossible to think well about a literary work (or any artwork, or any thing, really) without addressing its form.

Now we will turn to an aspect of the poem’s content by focusing on some of the ways in which the poem tells a story of events that occurred in a pagan, heroic culture, but are written down (and narrated) later by a (presumably) Christian writer. In Beowulf, we do not have a singular work originated by a singular mind or personality, but rather a story handed down, probably orally, for centuries before being written down, most likely by a monk with his own interpretation and worldview that differed from that of the characters whose story he tells. If in reading Beowulf you feel like you are ping-ponging back and forth between a pagan, pre-Christian world and a Christian one, congratulations: you are paying attention.

A little history: The A.D. 449 invasion of what we now call England by the Angles and the Saxons brought to that isle ancient Germanic culture and language. In 597 Christianity was formally brought to England from Rome through a mission ordered by Pope Gregory I. Gregory instructed the cleric who would become the First Archbishop of Canterbury—St. Augustine of Canterbury (not the more famous Augustine of Hippo)—to proceed slowly in converting this hinterland from paganism to Christianity. Rather than attempting to stamp out or outlaw pagan customs, the culture was gradually adapted to or transformed by Christian belief and practice. (This helps explain why many of our modern-day Christian holidays and traditions are intertwined with pagan ones.) This importation of Christianity from Rome brought with it Christian learning, texts, institutions, and clerics—eventually, too, the manuscript form of the old story of the old pagan hero from Geatland (now Switzerland).

Sometimes the Christian writer of Beowulf looks upon the subjects of his story with a distant eye, describing their pagan beliefs detachedly, as in lines 175-78 (Heaney translation) when he says that the warriors made vows at pagan shrines and offerings to idols: “That was their way.” This is such a tender expression, conveying such empathy despite the narrator’s clear disagreement. (There is so much we could learn from this example.) More obviously, throughout the story, particularly in describing various battles, the narrator ascribes the outcome to fate.

But in other places—many of them, in fact—outcomes are described as the will of “Almighty God.” At times, this seems to be the Christian writer re-interpreting the events and correcting the understanding of the people he writes about, as might any omniscient narrator explaining his story world. Other times, however, the narrator recasts the characters as thinking in Christian terms, as, for example, when he describes Hrothgar as giving thanks to “the Almighty Father” for Grendel’s defeat (line 527) and later, when Grendel’s mother takes revenge, “wondering whether Almighty God / would turn the tide of his misfortunes” (lines 1314-15). Beowulf, too, is frequently depicted as relying “for help on the Lord of All” (line 1272).

Beowulf himself is portrayed throughout the story as characterized by qualities befitting a pagan warrior (proud, boastful, and courageous) and at other times with qualities more closely linked to Christian virtues (humility, self-sacrifice, and submission to the will of God). The complexity of Beowulf’s character is one of the great achievements of the text, in my view.

The effect of this back-and-forth between the pagan world of the story and the Christian one of the writer can produce whiplash for the careful reader. Yet, I can’t help but think about future generations that might read our “Christian” texts, or listen to our “Christian” music, and watch our “Christian” movies and experience something similar as they see in ways we are blind to the same sort of assimilation of our surrounding culture into our understanding of what it means to be Christian.

One of the most dramatic of these “mash-ups” between the pre-Christian and the Christian worlds in Beowulf is the other central figure, Grendel.

There is so much to say about Grendel! But for now, I will focus on the ways in which Grendel embodies both pagan and Christian ideas, and does so in evocative and interesting ways.

Of course, because Grendel is a “monster,” and because Christians don’t believe in “monsters” (supposedly), our immediate sense of him is that he is the product of a pagan imagination and worldview.

Yet, the Christian writer of the text tells us that Grendel is one of those who dwelled among the banished monsters from Cain’s clan (lines 99-114):

…. And from Cain there sprang

misbegotten spirits, among them Grendel

the banished and accursed. (lines 165-67)

Grendel’s mother, too, the text says, was doomed to dwell in her watery cave since the time of Cain (lines 1260-63).

Most modern-day readers are likely to dismiss all this curse talk by merely grouping it in with other antiquated, unrealistic elements of the story: Beowulf’s retelling to Unferth of the several days he and his friend spent swimming in the ocean, the sea monsters he fought there, the spell that prevents weapons from harming Grendel, the underwater lair where Grendel’s mother lives (and Beowulf’s ability to stay underwater as long as he does to defeat her), and, of course, the very existence in the story of a dragon.

Readers today think of these things as “fantasy.” However, that category did not exist then as it does now.

Likewise, most of us today (me included) struggle to understand or explain rationally the passages in the Bible that mention giants (whether Nephilim or Rephaim), the Leviathan, the Behemoth, Cherubim, the Beast, or the sons of God (which may or may not be angels, depending on whom you ask) taking as their wives the daughters or men and having offspring (like Grendel, perhaps?). Such creatures—even when they appear in the Bible—that cross the boundaries drawn by the dictates of reason are more easily written off as myth or fantasy or just ancient old people not having a clue.2

But this crossing of boundaries is exactly what Grendel (along with his mother) represents in the story.

In the Old English of the original manuscript, Grendel is identified as a mearcstapa, literally a “mark stepper” or, more loosely translated, a “border-walker” (line 103).

Artist Makoto Fujimura insightfully applies this idea of the border-walker in his stellar book, Culture Care, to artists and others who serve society (especially the church) by leading from the margins, moving in and out of different communities, translating one community for the other, inhabiting the spaces in between tribes, and thereby serving as a bridge between polarized and fractured communities.3

But few understand, let alone love, the border-walkers. (Ask me how I know.)

Not all border-walkers are heinous, murdering fiend or demons (line 86) like Grendel. But more often than not, they are misunderstood, suspected, rejected, and outcast. (Ask me how I know.)

And this is what makes Grendel so relatable.4 He is all too human.

Grendel, the story tells us, is roused to his murderous rage— “harrowed,” the text says in line 87, which means “distressed”—upon hearing the revelry and song within the mead hall, a party to which he is not invited. Moreover, the song they sing inside is one of Creation, of the Creator, of the One whom his kin—and he—have long rejected. Grendel, the text explains, has “nursed a hard grievance” (line 87). He has become bitter.

Embittered, alienated, alone, Grendel does not kill in cold blood. Rather, he hotly desires what he does not and cannot have.

None of us is immune from such desires. Of course, we need not and ought not respond—literally or metaphorically—as Grendel does.

And yet Grendels are all around us.

Lord, bring us more Beowulfs.5

To be continued ….

P.S. Just a reminder that this newsletter is free to read! But by becoming a paid subscriber, you not only get to comment here (the comments are so, so rich!), but you also simply support my work not only here but everywhere else where you can find me. I’m grateful, of course, for supporting me just by being here and by reading my words.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

Of course, the folks at The Bible Project never shy away from such things! Here’s a podcast they did titled God, Abraham, Demons, and Giants: https://bibleproject.com/podcast/theme-god-e12-god-abraham-demons-giants-qr/

Also, this documentary film with the late Old Testament scholar Dr. Micahel Heisner, The Unseen Realm, examines biblical texts that mention the Nephilim and other “supernatural” beings and events in the Bible.

Makoto Fujimura, Culture Care: Reconnecting with Beauty for Our Common Life. Downers Grove, IL, InterVarsity, 2017.

Also, check out the substack of my friend Jon Ward, named for this very concept:

John Gardner’s classic 1971 novel, Grendel, retells the story from Grendel’s perspective: https://www.amazon.com/Grendel-John-Gardner/dp/0679723110

To be clear: Beowulf was an imperfect hero. My call is not for more knights in shining armor tilting at TikTok windmills. Beowulf (the character) has pagan and Christian qualities. We can rightly say of him: “that was a good king.”

That Grendel is a border-stalker is fascinating and so worth pursuing, as you've done here. It got me thinking about Paul's words, "genuine, yet regarded as impostors; known, yet regarded as unknown; dying, and yet we live on; beaten, and yet not killed; sorrowful, yet always rejoicing; poor, yet making many rich; having nothing, and yet possessing everything" (2 Cor 6:8-10) - they definitely have that liminal ring to them. Maybe there's a sense in which all genuinely Christian living in this world is to be found there often, too? But, yes, it is a dangerous place, given how susceptible to bitterness and "nursing a hard grievance" we are. When we're pushed to the margins we're at that same point on the border of another kingdom, one whose wisdom does not come down from heaven and is most definitely not peaceable (Jas. 3:13-18). But we can pray for one another, knowing that God gives grace to the humble.

Thank you so much for doing these lessons on Beowulf, Karen. I'm reading Heaney's translation and Tolkien's essay along with your insights. Tolkien brings up the discussion about whether Grendel is a "devilish ogre" or a "devil revealing himself in ogre-form," settling on the former, saying that he can only bring about temporal but not eternal death. This contrasts with the dragon who eventually caused Beowulf's demise, the dragon/serpent representing something much more insidious in literature than mere monsters. I was inspired to write haikus because of pondering these ideas :).

Grendel, a monster,

Of this world was begotten.

He had a mother.

Dragons lie on hoards

Of treasure guarded–they lie.

Like father, like son.