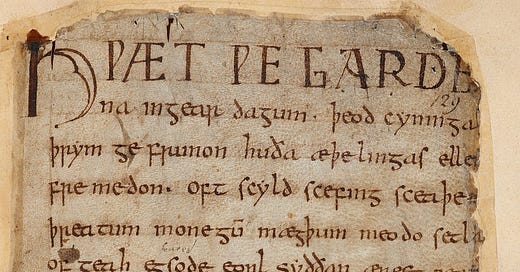

[First page of Beowulf in Cotton Vitellius A. xv., British Library]

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.” – Simone Weil1

In last week’s newsletter, where I lamented the state of higher education, I mentioned specifically the perilous conditions of the humanities right now.

In introducing Beowulf here, as promised, I want to start by talking about the value (and beauty) of studying foreign languages. After all, the language of Beowulf is a different language from our own.

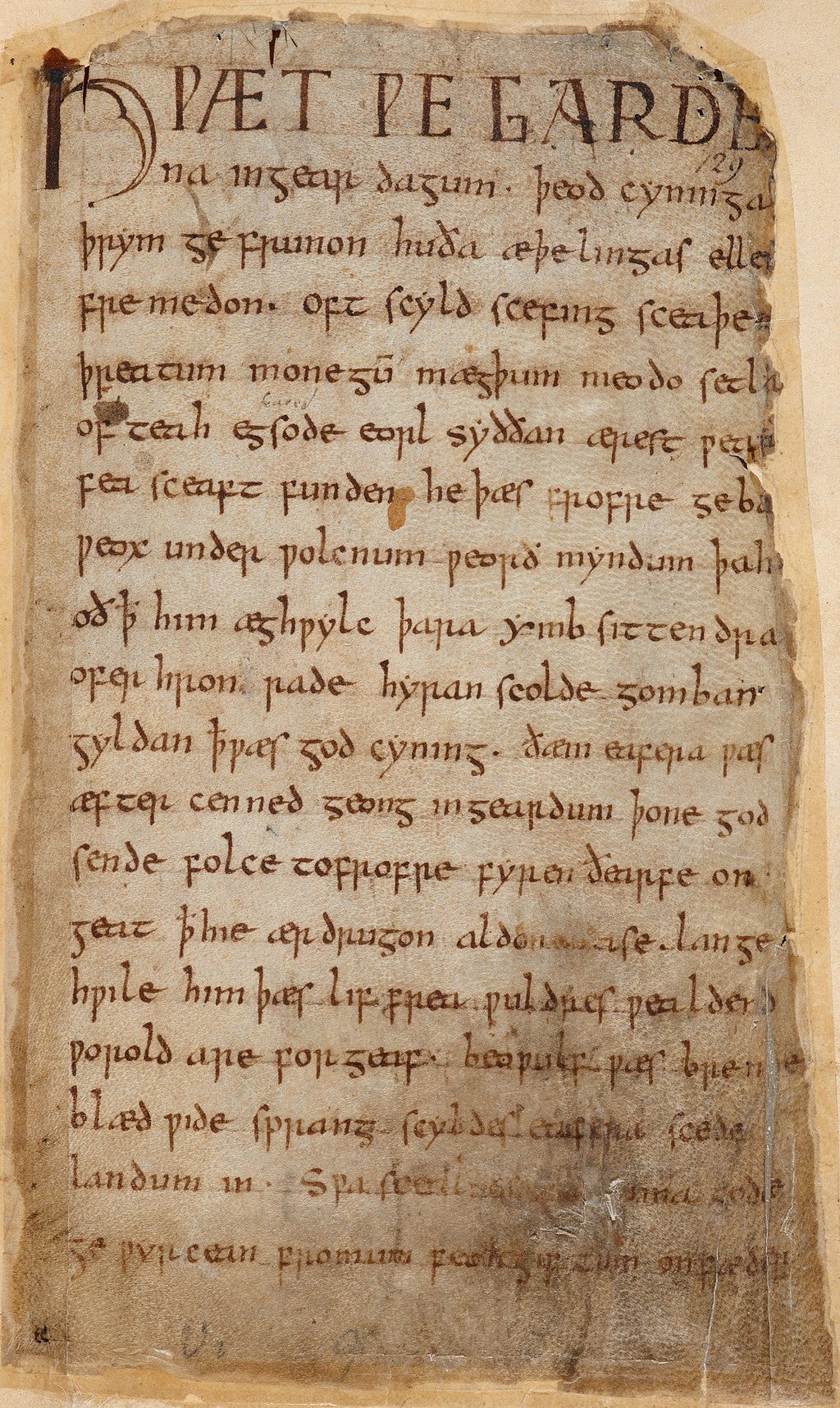

A lot of degree requirements have been changed or eliminated over recent years, but my undergraduate and my Ph.D. programs included foreign language requirements. That was fine by me since I didn’t just love English, I loved language. I studied French in high school and college (and was a French tutor during college), then studied Latin and Anglo-Saxon in my doctoral program. In fact, I spent one whole semester of my Ph.D. program translating Beowulf:

[One page of the translation I did of the entirety of Beowulf as part of my Ph.D. coursework.

I had a gigantic bag of vocabulary flashcards I made when I was studying Old English. Those are long gone.]

Now, I understand that not everyone is a language person (just like I am not a math person). But I have never understood how those who want to study English or writing can not be interested in studying other languages—because to truly love one language is to at least appreciate all languages. If one loves English and the study of English language and literature, then the study of other languages will—at the very least—increase one’s understanding of English. (Many pastors and seminarians have told me that they never understood English until they studied Greek. Bingo!)

There are countless reasons one should study another language (or languages), and it is not my purpose to cover them all here. What I will do is simply to encourage—exhort—anyone who has any desire and ability to pursue further education in any discipline to seriously consider studying a foreign language—especially if your direction is related at all to literature, writing, communication, or ministry.2 Now, today, I probably couldn’t translate my way out of a bag in any of the languages I studied so long ago. (What they say is true: use it or lose it!) Nevertheless, the way I understand and use English, the structures of my thinking and writing, and the way I read and even think were forever changed—stretched, grown, and improved—by my study of three other languages. Language is simply how human beings work.

So.

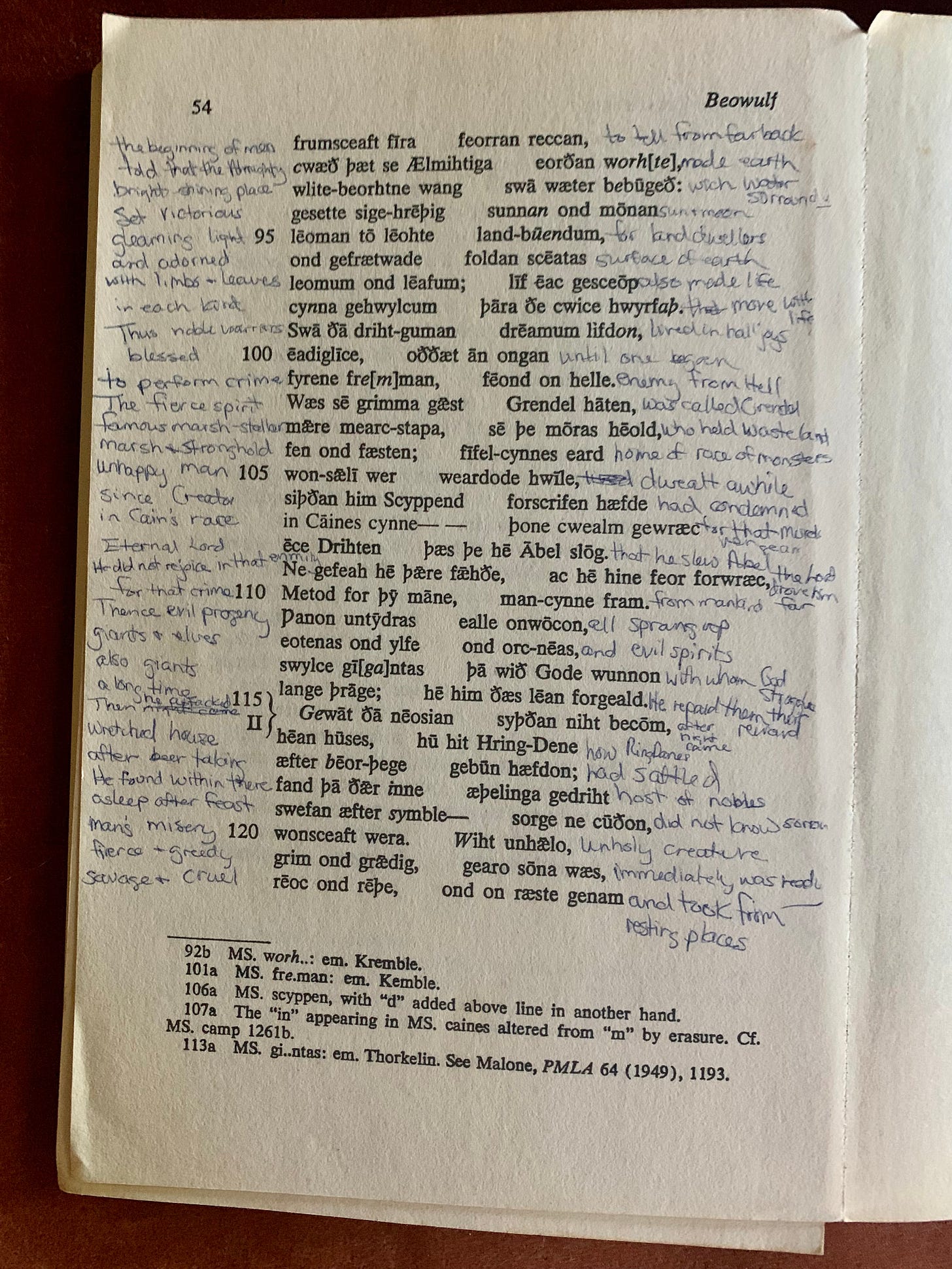

[My copies of Beowulf, not counting the versions in my Norton Anthologies]

Let us begin with Beowulf, the masterpiece of Anglo-Saxon literature, and let us begin with a little bit of history of English.

The English language has three separate periods: Old English (450-1150), Middle English (1150-1500), and Modern English (1500 to the present). I always tell my British literature survey students that if they learn one thing from my class, let it be that the works of Shakespeare and the King James Bible (first published in 1611) are not written in Old (or even Middle) English! As different as the language of those texts are from our English today, they are still written in Modern English. Old English (also called Anglo-Saxon) is so distinct from Modern English that it is utterly unrecognizable. It is another language altogether (which is why learning it fulfilled one of my two foreign language requirements for my Ph.D.).

A very short history of these three languages goes like this: Anglo-Saxon is a Germanic language. After the Norman invasion of 1066, Old English became so mixed with the French and other Romance languages that it evolved into an entirely different language, which we now call Middle English. (The English language today is so crazy and mixed-up because it is basically a mixture of German and French with Latin and Greek thrown in.) Words that come from Old English tend to be earthy, throaty, and short, while the words that derive from Latin or the Romance languages tend to be multi-syllabic but phonetically easier. Examples include think vs. ruminate, tough vs. impenetrable, teach vs. educate, light vs. illuminate, knight vs. cavalier, kinship vs. familiarity.

[Speaking of “weird” — that word comes from the Old English and Old Norse word “Wyrd” which means “fate.”]

A great way to hear how Old English sounds is to listen to this reading of The Lord’s Prayer found in The Exeter Book, a volume written in the 10th century.3

Beowulf was written down by an unknown author sometime between the 8th and 10th centuries about events set somewhere around the 6th century, a story that was likely passed down through oral tradition through the intervening years.

Before talking about the story itself, the content (we will save that for next week), let’s talk about the form of the work, for we can never understand any literary work (or any work of art) without attending to its form.

Beowulf is, first of all, a poem, and Old English poetry is characterized by a few features that are helpful to understand.

First, Old English poetry is written in half-lines: each line is composed of two short halves united by rhythm and sound. Not all translations will retain this feature visually, but often the structure and punctuation will try to express it naturally (as does Seamus Heaney’s).

Second, Old English poetry does not generally rhyme. Rhyme is simply one form of repetition. All forms of repetition are ways of achieving both emphasis and connection. Old English poetry achieves repetition within and between lines through alliteration (repetition of initial consonant sounds) as well as through assonance (repetition of vowel sounds), and consonance (repetition of consonant sounds anywhere). But alliteration is one of the chief literary devices found in Anglo-Saxon poetry and was revived later in Middle English. (We still like alliteration in Modern English. Just ask any Baptist preacher! Or stop in at any Dunkin’ Donuts or Krispy Kreme on your way to the Better Business Bureau.)

Nearly every line in Beowulf has alliteration, so there’s hardly any need to point it out. But one of my favorite examples in the Seamus Heaney translation is lines 710-11:

In off the moors, down through the mist-bands,

God-cursed Grendel came greedily loping.

Read that out loud.

The effect of these sounds—whether alliteration, assonance, or consonance—comes best through hearing rather than sight. Really, listen.

Hwæt!

Poetry is, of course, generally mean to be read aloud.

Speaking of reading aloud, I want to put a word in here for the benefits of reading (and listening) slowly. Literary texts are meant to be read deeply and immersively, not skimmed (or listened to on 1.5 speed!). You wouldn’t go to a museum and view the paintings past them as quickly as you can! Likewise, we can’t read literarily by reading a literary text the way we skim a newspaper article. So whether you are reading or listening to Beowulf (or both), look for and listen to the way the sounds contribute to meaning through connecting words and emphasizing ideas.

Some other common Anglo-Saxon literary devices found in Beowulf are variation, litotes, and the kenning.

A variation is a close repetition of an image with a different word. Again, this is a way of emphasizing something (it’s a device often used in the Bible, too). These are so common in Beowulf that they are everywhere. For example, line 12 says that “a boy-child was born to Shield,” and the next line refers to that child as “a cub in the yard.” Another example of variation is in lines 189-91: “So that troubled time continued, woe / that never stopped, steady affliction / for Halfdane’s son …” Or, in line 229, the “watchman on the wall” is immediately also identified as “the Shiedlings’ lookout.”

A really fun literary device you can find throughout Beowulf is the kenning—essentially a miniature riddle. (The Anglo-Saxons loved riddles, and there is an entire body of extant Old English riddles.) Kennings are everywhere here: whale road or swan’s road (which means sea), word hoard (mouth), world candle (sun), life’s house or bone house (body) are just a few examples. Even the name Beowulf is believed to possibly a kenning. Translated "bee’s wolf” it would signify “bear” (whose prey is the bee’s honey).

Perhaps my favorite literary device is litotes, which is ironic understatement. Irony is delicious in its own right, but the way Beowulf uses this device conveys powerfully the fatalistic mood of the pagan heroic culture which (despite the Christian layers added to it, which we will get to next week) really was rooted in a dark, bleak outlook that matches the cold, bitter isolated life of the ancient northern climes. I just love the sardonic tone of litotes like this: “But the earl-troop’s leader was not inclined / to allow his caller [Grendel] to depart alive” (lines 790-791). And Grendel’s “fatal departure was regretted by no one” lines 840-41). (Another translation of this passage I like better is “His parting from life was no cause for grief.”) One that always makes me laugh is in lines 138-39 when Grendel is attacking: “It was easy then to meet with a man / shifting himself to a safer distance.” I bet it was!!!

Alongside these smaller devices looms the big picture about the form of Beowulf. In some ways it might be seen as an epic. It features a number of similarities to classical epic: a noble hero whose heroic deeds affect the fate of a nation, catalogues of people and treasures, supernatural feats, and divine intervention. Its meandering plot and syncretic mythology lead some to think of it more as a folk epic than one the follows the classical form.

J.R.R. Tolkien famously declared Beowulf was neither, saying, “It is an heroic-elegiac poem; and in a sense all its first 3,136 lines are the prelude to a dirge.”4

Next week, we’ll dig into the story.

Additional resources:

You can read Beowulf online here—and the same translation is available on Audible.

Lots and lots of resources are here at Beowulf Resources.

In the early twentieth century, a medieval ship was discovered at Sutton Hoo, the relics of which give life and detail to the Beowulf story.

The Dig is a film inspired by the discovery made at Sutton Hoo. I highly recommend it as a film in its own right.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

I also will add for anyone who has (or is) a high school student studying a language, continue that study in college! And do not start college coursework with 101 just to get easy credits. Begin at the level you have attained so that you can advance as far as you can in that language. This is the kind of thing that sets one college degree apart from another.

https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/exeter-book

J. R. R. Tolkien, Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics https://jenniferjsnow.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/11790039-jrr-tolkien-beowulf-the-monsters-and-the-critics.pdf

Breaking Beowulf news: https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/jeff-bridges-dave-bautista-beowulf-grendel-movie-1235896022/amp/

Thank you for this. I didn’t know I needed it. But as I began to read about the literary details it felt like sitting down to a gourmet meal. Suddenly it became clear that I’ve been used to a diet of Cheetos by comparison.