Readers, our good friend Jack Heller is back with another guest post which will wrap up our many weeks on John Milton. This essay also offers a great segue into our next slow read: John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress. Jack Heller retired in 2023 after 21 years as an English professor at Huntington University in Huntington, IN. He specialized in English literature up to 1800, Shakespeare and Renaissance drama, and African American literature. He authored one book on the English dramatist Thomas Middleton, Penitent Brothellers, and a few articles on Shakespeare, including one on Dogberry in Much Ado about Nothing and one on the sacraments in Julius Caesar (not online). Heller has also done an online video interview with Jessica Hooten Wilson about Ernest Gaines and his novel A Lesson before Dying. If you would like a copy of the Caesar essay or otherwise want to contact Heller, you may reach him at jack.heller62@gmail.com.

And one more matter before we get to the essay: I will soon host a Zoom meeting for paid subscribers. I have posted and sent an email invitation with the details, so watch for that! I will send the invitation out again, so if you aren’t a paid subscriber yet, it’s not too late to become one and join us!

Now, without further ado, here’s Jack:

An answer to this question is probably more significant to Milton’s role in English political history than to his reputation among literature scholars. However, when writers are labeled Puritans, readers will bring to their works assumptions about their theology, politics, moral stances, and temperaments. Milton may be considered a Puritan, but we will want to set some parameters on the meaning of “Puritan” to see how well the label fits and how it may keep us from seeing and appreciating the fullness of his literature.

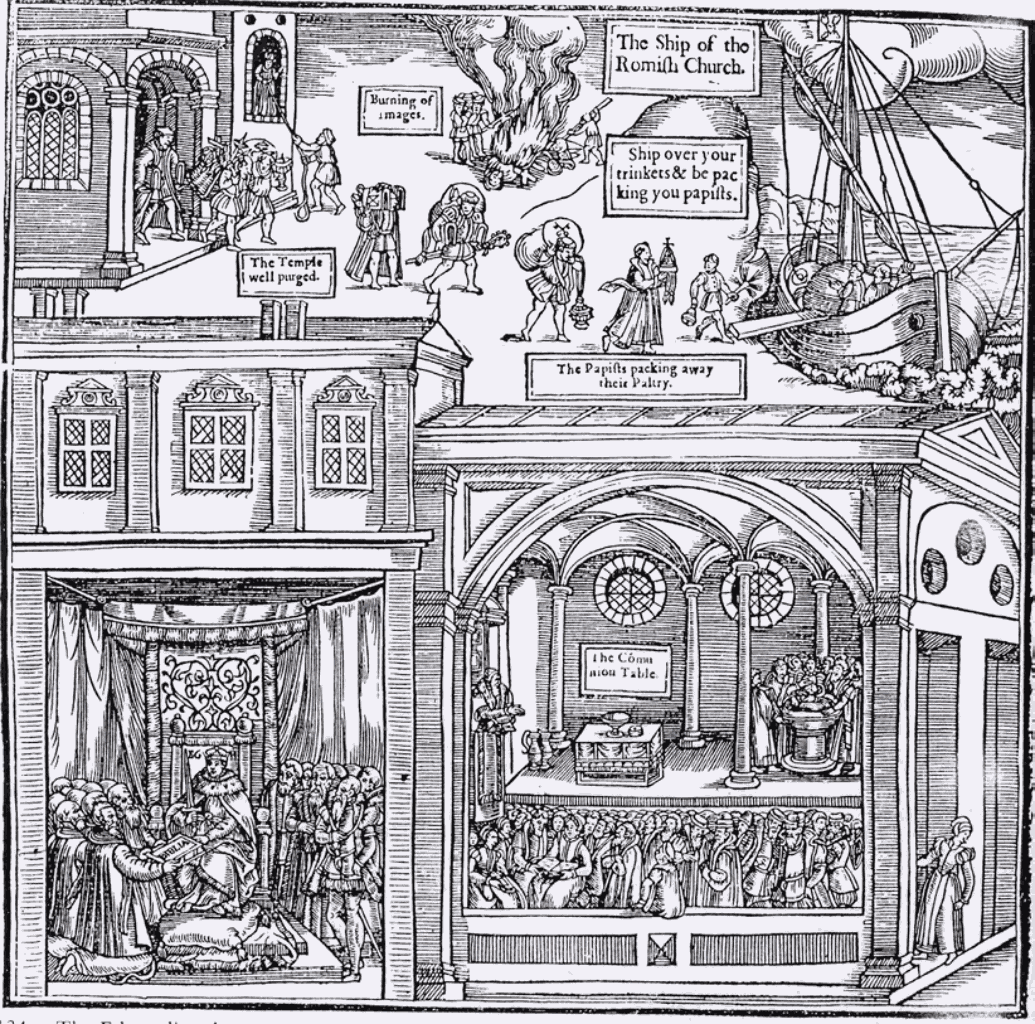

Puritans and Puritanism have always been vaguely defined, but the earliest uses of the terms, from the 1560s to the late 1580s, refer pejoratively to religious-political partisans. Puritans in these years usually held to Reformed Calvinist theology, but Reformed theology was also prominent in the Church of England. The first Puritans believed that once the English Church had separated from the Roman Catholic Church, it should reform church practices entirely from the last common practices that the English and Roman churches shared: no vestments, no clerical collars, no books of church order, no statuary, no stained glass windows, no ornamentation, no reverence for the saints, sacraments limited to baptism and the Eucharist (or Communion), and less liturgy and fewer scripted prayers. From the early years of the Church of England up through to 1580s, the destruction of religious ornamentation, called iconoclasm, was widespread and practiced within many of the local churches and chapels.[i] Writers such as John Foxe (of the Book of Martyrs) and Edmund Spenser (who wrote The Faerie Queene) favored iconoclasm, but they did so while affirming the authority of the Church of England, and thus they were not separatists. So far, the writers who were in church ministry that Karen Swallow Prior has featured on this Substack, John Donne and George Herbert, have been Church of England priests. They were in favor of church rituals and ornamentation, and therefore they were not Puritans.

In the early 1580s, a new strand of Puritanism developed: rather than reforming the Church of England, the adherents wanted to separate from it. The minister and writer who was an early leader of this Puritan strand was Robert Browne; he published his pamphlet A Treatise of Reformation without Tarrying for Anie in 1582. His initial followers were called Brownists, and though Browne’s theology was still Reformed, his argument appealed to English Anabaptists, Congregationalists, and Baptists. The Pilgrims who left England for the Netherlands and then eventually for North America were Brownists. While Browne himself eventually returned to ministry within the Church of England, much of the stereotypically starchy image of the Puritans comes from his followers.

Yet even that stereotype has important exceptions. King James regarded all separatists as Puritans, but he also claims,

[As] to the name of Puritans, I am not ignorant that the style thereof doth properly belong only to that vile sect amongst the Anabaptists, called the Family of Love; because they think themselves only pure, and in a manner without sin, the only true Church and only worthy to be participant of the Sacraments, and all the rest of the world to be but abomination in the sight of God. Of this special sect I principally mean, when I speak of Puritans; divers of them as Browne [et al], having at sundry times come into Scotland . . .” (my modernization from the text of King James’s Basilicon Doron).

The Family of Love sect was a subset of Anabaptists who, according to rumors and satires, believed that their sanctity was its own guard against the impurity of illicit sexual activity; in other words, they were believed to be a free love cult. Furthermore, the term “Puritan” was now also used to label theological Arminians. Whether the Family of Love were Puritans or not, “Puritan” is now stretched by King James and others to include every person of professed Christian religious faith who does not follow the Church of England or the Roman Catholic Church.[ii]

During the 1580s and into the 1590s, Puritans and Puritanism also become more associated with the reform of public morals. In particular, men who have been identified with Puritanism—such as Stephen Gosson, Philip Stubbes, John Rainolds, William Crashaw, and William Prynne—wrote against stage plays and theaters. Their arguments could be quite lively in their own way; here is Philip Stubbes from his Anatomy of Abuses (1583):

Mark the flocking and running to theaters and curtains, daily and hourly, night and day, time and tide to see plays and interludes, where such wanton gestures, such bawdy speeches, such laughing and fleering, such kissing and bussing, such clipping and culling, such winking and glancing of wanton eyes, and the like is used, as is wonderful to behold (my modernization of the text).

The stereotypical Puritan killjoy arises with these men’s opposition to plays, and they are satirized by William Shakespeare with Malvolio in Twelfth Night and Angelo in Measure for Measure, as well as by the characters Tribulation Wholesome, Ananias, and Zeal-of-the-Land Busy in the comedies of Ben Jonson.[iii] The Puritan Parliament of 1642 finally closed all of the English theaters; they did not reopen until 1660. Yet the Puritan opposition to the theaters is not the whole story of English Protestant engagement with theater in England between 1550 and 1660. John Foxe and Thomas Norton, the first English translator of John Calvin’s Institutes, both wrote plays; John Foxe wrote his comedies in Latin, and Norton wrote Gorboduc, a source for King Lear.

Generalizations about Puritanism become especially difficult after 1620, during the last years of James I’s reign, through his son and successor Charles I’s reign, and on through the commencement and conclusion of the English Civil War. If we take for granted that all Puritans opposed the theaters, we will run up against the reported favorable Puritan reaction to the 1624 play A Game at Chess.[iv] If supporting the government of the Puritan Oliver Cromwell is a sign of Puritanism, what are we to make of the poet Andrew Marvell, who supported Cromwell and wrote mostly in a secular vein? When I read now about John Bunyan, he is more commonly discussed as a Protestant dissident rather than as a Puritan. He and his fellow Baptists had so little power either within ecclesiastical structures or within British politics that they couldn’t hope to reform or purify anything. Their focus was more on the autonomy of the local congregation and on personal sanctity; Vanity Fair can only be fled, not rehabilitated.

John Milton was aligned with the political Puritans who came to dominate the British Parliament that eventually deposed and executed Charles I in 1649. Milton was Parliament’s best polemicist, with pamphlets arguing for the reform of civil government, for the reform of church government against both the structure of the Church of England and against civil government control generally, and perhaps most disturbingly, in defense of the execution of King Charles I. In his pamphlet Of Reformation, Milton argues that the Bishops Thomas Cranmer, Nicholas Ridley, and Hugh Latimer were “halting, time-serving prelates”; all three bishops are valorized in John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments as martyrs for the true faith against Rome.[v]

Milton himself uses the word “Puritan” and its cognates “Puritanism” and “Puritanical” at least sixteen times in his prose books and pamphlets.[vi] Most commonly, Milton identifies “Puritan” as a pejorative that England’s kings and bishops have used against faithful Christians. He uses “branded with the name of Puritans” in two pamphlets against monarchical authority in the English church (Of Reformation and The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates). What seems counterintuitive in the twenty-first century is that Milton aligns with the Puritans, not because he was especially predisposed to moral strictness, but because Puritanism as he portrays it is on the side of greater freedom. Anticipating Areopagitica, in one instance Milton complains of bishops “confining” pamphlets against themselves “to darkness, but licensing those against Puritans to be uttered openly.”

Milton moves away from the views that are stereotypically Puritan when the supposed Puritan view would limit his perspective on freedom. Milton wrote the first major argument in favor of divorce, and it had taken until the 20th century to have cultural approval. His theology of Christ as unequal to God the Father had no proponents (though it is now similar to idea of the eternal submission of the Son to the Father).

Perhaps most strikingly, Milton diverges from the Puritans who opposed theatrical performances. He does once complain about Sunday performances of plays in the court of King Charles I. But after his aforementioned complaint against the publication licensing powers of the bishops, Milton argues against all licensing power to the same Puritan Parliament he usually defends, and throughout Areopagitica, he refers to ancient Greek and Roman dramatists: Euripides, Menander, Plautus, and Aristophanes (about whom Milton notes his exceptional vulgarity). Elsewhere, Milton writes a sonnet praising Shakespeare to preface the third folio of his plays, and he quotes Richard III in Eikonoklastes to criticize Charles’s hypocrisy.

And Milton even tried his own hand at writing for theatrical performances. Two of his works, Arcades (date uncertain) and A Mask (1634), are musical pageants extolling the virtues of women of the Egerton family, an aristocratic family that also commissioned works from the dramatist Ben Jonson.[vii] A third work, Samson Agonistes (1671), is a closet drama—a play written to be read rather than to be performed—based upon the Old Testament character. These works are rarely performed today, and when they are, they are performed as readers theater, sometimes with a quartet accompaniment. Even though Milton did not focus on becoming a dramatist, his appreciation of theater certainly contrasts with the anti-theatrical prejudice we often associate with the Puritans.

As with “Puritan,” so with so many labels we use today: conservative, liberal, evangelical, mainstream, fundamentalist. John Milton was a Puritan, but let him modify how we use the term rather than letting the term box him into our preconceptions.

[i] If you have an opportunity to visit Stratford-upon-Avon, Shakespeare’s hometown, you should visit the Guildhall Chapel, the chapel of the school Shakespeare attended. Shakespeare’s father, John, was paid two shillings for “defasyng ymages in ye chapell.” Evidence of the destruction remains, and Shakespeare dramatizes an iconoclastic mob in Act 1, scene 1 of Julius Caesar.

[ii] If one wants to read good literature from the separatist Puritans, explore the poetry of Edward Taylor, a Massachusetts minister whose religious poetry is similar to John Donne’s, and Anne Bradstreet, who writes about her domestic life in Puritan New England.

[iii] Shakespeare also gives a brief jab at the Brownists in Twelfth Night in a line from Sir Andrew Aguecheek (3.2.30). The Jonson plays are The Alchemist and Bartholomew Fair. I have written at length about Puritanism and theater in my only book, Penitent Brothellers: Grace, Sexuality, and Genre in Thomas Middleton’s City Comedies (2000). I am quoting Stubbes from my own book.

[iv] A Game at Chess was written by Thomas Middleton. Judging only by what we today would call box office, it was the most successful play in Renaissance England. The history of its Puritan reception is too complicated to elaborate here, but this article from the Folger Library summarizes its political controversy and popularity. If you would like to know more, see my book, cited above. The play itself is hard to find in an easy-to-read format online, but it is readily available in print editions.

[v] For the reform of civil government, see for example Milton’s The Ready and Easy Way to Establish a Free Commonwealth (1660). Milton has several pamphlets on reforming church government, among them Of Reformation Touching Church Discipline in England (1641) and The Reason of Church Government Urged against Prelaty (1642). The arguments in defense of executing King Charles appear in The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates (1650) and Eikonoklastes (1650). The best website devoted to John Milton, The John Milton Reading Room, has all of Milton’s English poetry and most of his English prose, including every text I am mentioning: https://milton.host.dartmouth.edu/reading_room/contents/text.shtml#common

[vi] I reach the number 16 by counting the uses of “Puritan” in the prose works included in Dartmouth’s John Milton Reading Room, cited above. There are no uses of the word in Milton’s poetical works. To find the passages I am referencing, use a search engine to find the quoted words in the texts that I have linked

[vii] A Mask is sometimes titled Comus, after the villain of the work. Dynamic villains seem to be one of Milton’s artistic strengths.

If I can tell tales out of school (I don’t think Jack will mind), as is usual in writing most things, he didn’t know in the drafting process how this essay would end up. And I love the ending. Just love it. Ah, the magic of writing.

Also, I love, love, love the line: “Vanity Fair can only be fled, not rehabilitated.” What a punchy way of expressing an entire theological view in contrast to some others.

Glad to have your words here again, Jack!

It is ironic that Milton identified Puritanism with freedom. It was the Puritan government for whom Milton wrote that banned theatres and sports, regulated plain clothing, enforced strict Sunday observance, held monthly fast days instead of feast days, banned the celebration of Christmas, and disenfranchised Roman Catholics - the leader of that Puritan government, Cromwell, attempted a genocide of Irish Catholics, with his soldiers committing brutal massacres in Drogheda and Wexford in 1649. Yet Milton continued to support the Puritan faction, even when the rest of England, tired of Cromwellian strictures, invited Charles II to restore the monarchy to England in 1660. Milton may not personally have observed all those Puritanical strictures, but then again, neither apparently did Cromwell,who is said to have given himself more license to enjoy life than he granted the public.