Readers, we are halfway through our slow read of Paradise Lost. What an accomplishment! This week we will take a collective breath (or perhaps catch up on the reading …) with an interlude in the form an an essay by Samuel Loncar, who (I’m proud to say) was a student of mine many years ago. Samuel was a treasured student then and is a treasured friend now. Here is some information about him. I hope you will explore more of his work after reading his essay!

The philosopher and religious studies scholar, Samuel Loncar, Ph.D. (Yale), is the Editor of the Marginalia Review of Books and Founder of the Becoming Human Project. Relevant recent or forthcoming work includes his co-authored chapter, "The Historical Critique of Heresiology in the Seventeenth Century and the Origins of John Milton’s Arianism"; his first series Origin: How Philosophy Remade Science and Religion; his current series, Apocalypse: A Philosophy of Angels; as well as his book, Becoming Human: Philosophy as Religion from Plato to Postuhumanism, appearing with Columbia University Press. Read more at his Substack, @Noussphere.

***

The Revolutionary Angels of John Milton

Milton! Thou shouldst be living now…

England hath need of thee…

Thy soul was like a Star, and dwelt apart:

Thou hadst a voice whose sound was like the sea:

Pure as the naked heavens, majestic, free.

William Wordsworth, “London, 1802”

I. A Protestant Star Rises

Milton’s Angelology is nothing less than a cultural revolution, a radical return to the mysterious world of ancient philosophy and spirituality from which the 1st century Jewish man, known as Joshua the Messiah (the biblical name of “Jesus Christ,” inexplicably elided and untranslated in Christianity), emerged to transform human history.

By the 17th century, Protestantism’s focus on the supreme authority of Scripture alone—sola Scriptura—combined with intense Catholic polemics, led to a century of enormous learning, erudition, and historical debate. The idea of Christian orthodoxy was contested and in many ways reborn in this period.

For John Milton, all theological claims had to have a biblical foundation if they were to compel belief. The only valid idea of heresy was a person who believed on the basis of authority, rather than their own understanding of Scripture—a precursor to the Enlightenment’s rationalism and inheritor of the philosophical Christianity of the early Greek fathers, especially Origen of Alexandria.

Milton’s approach was inclusive of practically all then-existing Christian groups, except Roman Catholics, precisely because they did not ground their authority on the Bible alone. (See my co-authored chapter with R. Bradley Holden, and Holden’s chapter in the Oxford Handbook of Calvin and Calvinism). This led Milton to the intensive lifelong study of all things necessary to understand the Bible.

Even in an age of great scholarly achievements like the 17th century, Milton became a luminary, distinguished not only as a poet and reformer but as a scholar of international fame.

From 1649-1659, he served as Oliver Cromwell’s Secretary of Foreign Tongues, and was at ease in Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Aramaic, Syriac (a later form of Aramaic in which many important traditions of the Bible are preserved), Spanish, Italian, and French, among others.

Milton’s republicanism, his defense of regicide, and his intellectual service to Cromwell’s Commonwealth make him a perfect example of what I call theopolitics, the seamless unity of theological and political ideas that baffles people today, yet was the norm throughout history.

Milton’s angels are thus no mere repetition of the angelic hierarchies of the Middle Ages, though he knows and respects these ideas. Nor are they the poetic but impractical musings of an academic, though Milton was both scholar and poet. They are the lifeblood of Milton’s own existential vision of human freedom, for which he risked his life.

II. A Cosmic History of Revolutions

Paradise Lost depicts history as the dramatic effect of a heavenly rebellion that can only be repaired through an earthly revolution, effected finally by the Son of God, and assisted by the free and unfallen angels, helping humans, Adam and Eve, understand and realize their destiny in the cosmic republic of creation.

The unity of Milton’s political republicanism with his poetic theology of freedom reflects his insight that tyranny is the inevitable logic of sin. The false and chaotic regime of sin, born from the misuse of freedom, threatens not only individuals, but societies, and even the very world itself.

Milton’s epic depiction of the tyrannical cosmic logic of sin and its undoing by the Son’s free sacrifice unified all of paganism into a biblical history of the cosmos, just as the church fathers sought to integrate the wisdom of the pagan world into its corrected fulfillment in God’s true Wisdom and Story, the Logos.

This darkly thrilling epic spanning Heaven and Hell by the power of poetry makes John Milton the John the Baptist of the Romantic movement in English literature. It is important to recall that it was the 19th century Romantics who gave us the canonical Milton and Shakespeare, seeing in both a sublime vision of human freedom and thus tragedy, and, in Milton, an affirmation of political freedom as a necessary consequence of our spiritual dignity and destiny.

What is this vision, simply put? That the God of Israel, who made the world good, graciously sets fallen humans free from the tyranny of their self-destructive rebellion against goodness.

What is this freedom for? What is its purpose? The rabbi and apostle Paul, beloved of Milton, puts it clearly: “For freedom you have been set free.”

III. Raphael’s Message: The Existential Revolution

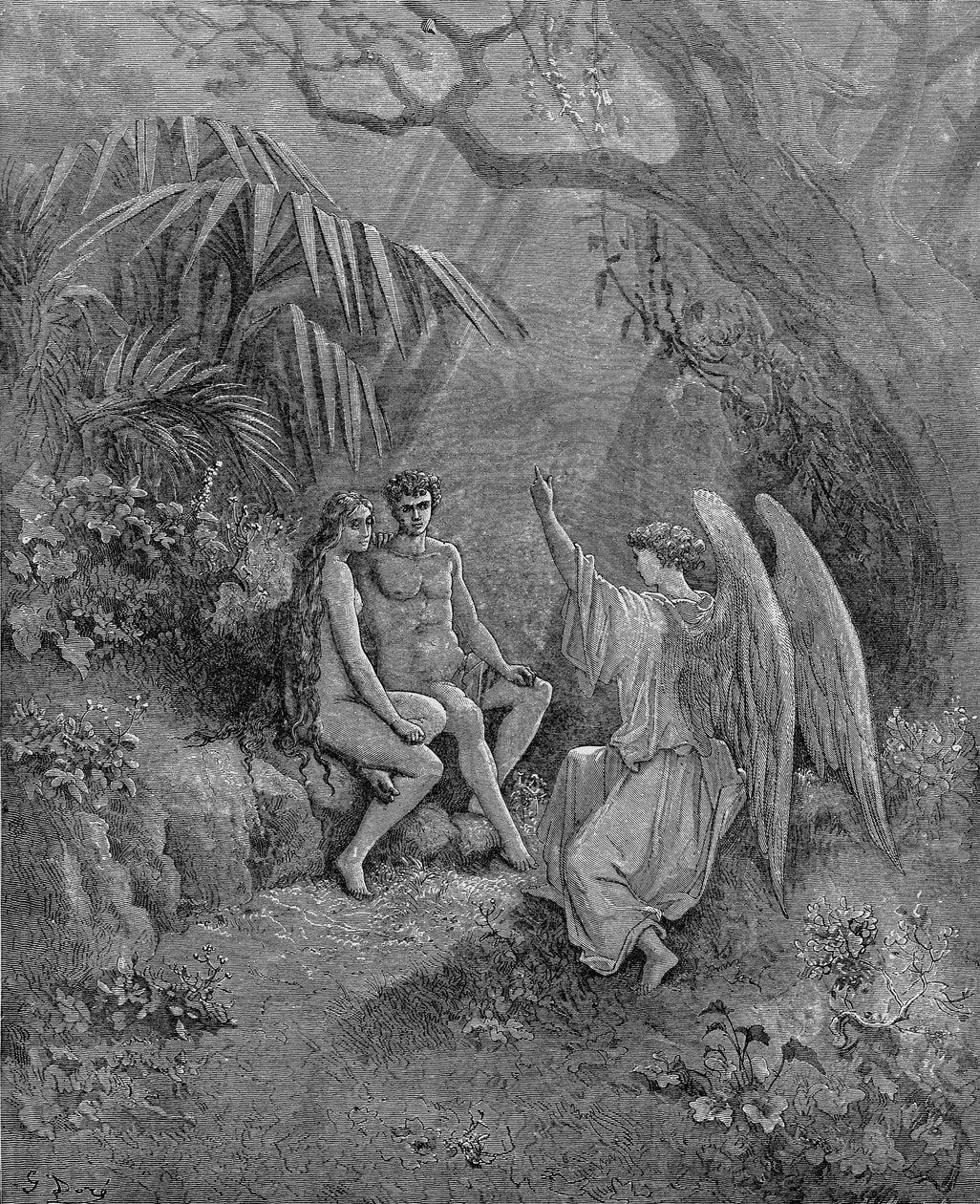

The keystone to Milton’s radical theology is the archangel Raphael’s stunning speech in Book 5 of Paradise Lost, a kind of summa of theology and the mission of humanity in creation. His approach is descried and beautifully described by Adam:

“Haste hither Eve, and worth thy sight behold

Eastward among those Trees, what glorious shape

Comes this way moving; seems another Morn” (5.308-10)

Raphael, like all true angels in Milton, can physically eat and commune with humans, and Raphael explains humans may eventually ascend to become like himself.

“Your bodies may at last turn all to spirit

Improved by tract of time, and winged ascend

Ethereal as we…” (5.497-499)

***

“Time may come when men

With angels may participate.” (5.493-494)

This is the awesome and still mysterious destiny Milton holds out for humanity, hints of which are found in the great scholar and lover of Milton, C.S. Lewis, whose space trilogy is a sequel to Paradise Lost for the space age. In his magnificent sermon, "The Weight of Glory,” he puts it plainly: “It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest and most uninteresting person you talk to may one day be a creature which, if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare. All day long we are, in some degree, helping each other to one or another of those destinations.”

A serious thing indeed, and the very reason we are captivated still by Milton’s Paradise Lost. For in it we find the same magnificent and solemnly celestial vision of Origen of Alexandria in the 3rd century, and of C.S Lewis in the 20th, who, different as they were, all came to regard space, the heavens and its inhabitants, as the essential backdrop, and even destiny, of the human species and its power of free will.

In this sublime ascension narrative of humanity, a time is coming when humans truly know who they are and choose to become themselves in the Truth. Then, the creator of the heavens promises to dwell with humanity on earth, and earth and its heavenly surroundings will know each other once again, yet anew, for the very first time. For the Truth makes all things New. “For the earth will be filled with the knowledge of the glory of the LORD, as the waters cover the sea.”

Acknowledgements: It’s a special honor and pleasure to write for my college English teacher again, so thank you, Karen, for inviting me to The Priory!

***

Next week: Book 7.

Also, I think we all have decided to read The Pilgrim’s Progress together! We will rest a bit after finishing Paradise Lost. But if you want to plan ahead, you might consider getting a good edition for yourself. As the second most published book in the world (after the Bible), there are many. One word of caution is that many of these are redacted, abridged, and modernized—so there are great variations. This is the old copy I use, from Oxford World Classics. I’d say you are safe with any unabridged edition with original marginalia (and editorial notes also help).

***

Thank you and welcome to new subscribers and supporters! You mean the world to me! A special thank you to those whose paid subscriptions support this work so that others who can’t pay can benefit. Your help not only supports my work here, but all of it out there in the world. (And it is surely a hard world out there sometimes!) Paid subscribers are able to comment (and I really love our discussions), so that’s one more way you can contribute to this little community. Another way you can support my work is to share these posts with others through social media or personal contacts. Thank you for being part of it in whatever way you can!

A linguistic side note on the opening aside: I don't think it is at all inexplicable that Jesus Christ is untranslated. After all, it is a transliteration of the kione Greek, Iesous* Christos, which is the language in which the New Testament is written. Koine was a common trade language in the Roman world - the earliest missionaries who introduced the name of Jesus to the pagans of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East would have spoken, and read, the koine form of his name to their hearers. I understood this better when I was learning the West African language of Wolof. There, the Wolof word for God, Yalla, is a transliteration of the Arabic word for God, Allah, introduced to the West Africans by North Africans - there just isn't another word to use for God in the language. After all, Joshua (or Yeshua) the Messiah is only a transliteration from Hebrew. A full translation of the name meaning into English would be Saviour the Anointed One, which is much less personal than the transliteration.

*The pronunciation shift from 'Iesous' to Jesus is due to differences in ability to pronounce vowels and consonants between languages - the shift from 'Ie' (a 'y' sound) to 'Je' seems to have happened as Latin split into regional pronunciations, as the Latin version, Jesu, may be pronounced with a 'y' or 'j' sound. Full translation of the name meaning might help with pronunciation, but it would also wipe out the familiar sound of the name to the person. For example, in my travels I found my name is nearly unpronounceable to Spanish and Portuguese speakers. Some of them with a little knowledge of English, tried to translate what they assumed was the meaning of my name into their language and call me Santa, because they thought Holly meant 'Holy'. I had to laugh and say, no, my name is untranslatable because I'm actually named after a plant - Old Germanic speakers called it 'Holegn', which morphed to 'Holi' in Middle English, and thus to 'Holly' in modern English. But had my name translated to Santa, it would have taken me a long time to associate the sound with myself, especially given the North American tradition of Santa Claus.

This was excellent, Samuel. Wow. I am one who has been captivated by this book. Your essay was spiritually encouraging as well. Thanks.