How I met John Milton's Areopagitica

And the father who blacked out his daughter's college reading assignments

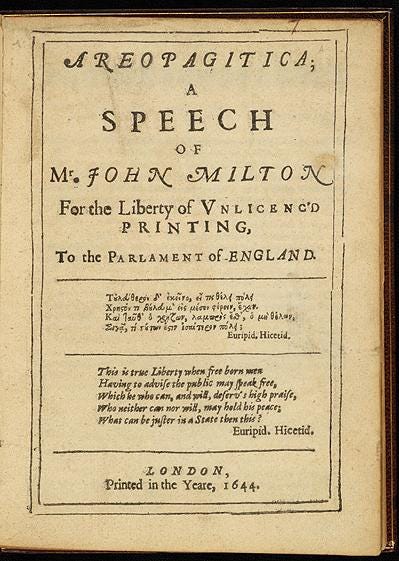

[http://smu.edu/bridwell_tools/specialcollections/Heresy&Error/Heresy.13.htm, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=79068707[

To begin our discussion of Areopagitica, I thought I would offer an excerpt from my chapter on it from my memoir, Booked: Literature in the Soul of Me (T. S. Poetry Press, 2012). I know that some of my readers here have read this memoir. I hope those who have enjoy re-visiting this story in this fresh context! Because my real hope is that by giving a bit of my own personal background with this work by Milton, it might tempt more of you to read Areopagitica. It’s much more engaging and compelling than the title suggests! At about 50 pages long, Areopagitica is short enough to read in one or two sittings. I hope you will do so (if you’ve not already) and chime in on the discussion.1 Over the next couple of weeks or so, I will highlight some passages from it.

***

Some years ago, when I was a college administrator and English professor, the parent of a freshman came to me to complain about a story being taught in his daughter’s literature class. The story was “Rape Fantasies” by Margaret Atwood. It’s a humorous story about a serious topic, and the gist of it is that in coping with the ever-present possibility of rape in our lives, women think about what they would do or how they would handle such a threat if it arose. The fact that the characters in the story don’t think about rape in very realistic terms only emphasizes just how unthinkable such a thing is.

Well, this father was having none of it. He feared the story might lead male students to think women want to be raped and that it was traumatic for female students (namely, his daughter) to read. He would not allow her to read it, and he thought the professors in my department shouldn’t be assigning it to students. He had read it himself, he explained to me, because he read all of his daughter’s assignments before she did and blacked out with a marker anything he thought she shouldn’t read. He thought this entire story needed to be blacked out; I wish I were making this up.

“But rape,” I tried to explain to him, “is a very real threat that women have to live with and think about.”

“Not my wife or daughter,” he shot back. “They don’t have to think about it.”

I could see that the conversation was going nowhere.

This man needed a reality check. “Well, I fantasize about rape every day,” I said.

He squirmed in his chair and looked down. “I don’t need to know about that,” he muttered.

“Why, yes, you do,” I answered, my voice growing firm.

“You see, I’m a runner, and I live out in the country where I have to decide every day whether or not I want to run on the main road, trafficked by logging trucks, or on a quiet, deserted dirt road.

Most days, I choose the dirt road. And on the rare occasion when a vehicle comes down that road, I pay attention. I know all the regulars by heart, and if an unfamiliar one approaches, I think about which way I’ll head through the woods if I need to, and I keep my phone at the ready. That’s what I fantasize about every day.”

He was quiet for a moment, but a very short one. “Well, my daughter doesn’t need to worry about that.”

“But someday when she’s out walking on the street at night, alone, she will,” I insisted.

“No, she won’t. Because she will never be out walking the street at night alone,” he said, shaking his head. “I’ll never let her do that.”

And to that there was nothing I could really say.

John Milton said it better than I ever could when he argued that books should be “promiscuously read.”

Milton made this argument in 1644, in an anti-censorship tract titled, Areopagitica. In the midst of the English Civil Wars, when the price for a wrongheaded idea might well be one’s head, Milton argued passionately in this treatise that the best way to counteract falsehood is not by suppressing it, but by countering it with truth. The essence of Milton’s argument is that truth is stronger than falsehood; falsehood prevails through the suppression of countering ideas, but truth triumphs in a free and open exchange that allows truth to shine.

I learned about John Milton and his most famous work, Paradise Lost, in college, but I wasn’t introduced to Areopagitica until graduate school. Oddly enough, even then it wasn’t in a class but through a remarkable series of events.

I had taken a couple of classes with a professor who seemed to me to be one of the most liberal, perverse, and intellectually intimidating people I had ever known. I read my first (and last) work of pornography as an assignment in his class (it was eighteenth-century pornography, but pornography nonetheless).2

It seemed as if this professor was always saying the wickedest things, and I could never tell if he was serious or if he just thought that being provocative was part of a professor’s job within one of the most liberal departments in a liberal state university.

One evening, while conducting a make-up class in his home, the professor regaled the grad students with tales of shocking his undergraduates in a course he taught on the First Amendment. One of his favorite tactics was to show them the “homoerotic” photographs of the acclaimed and controversial photographer Robert Mapplethorpe. When the professor mockingly described the indignation of “some redneck born again” student, I called him out. In front of everyone. I didn’t think it likely that it was only the “born again” undergrads that were queasy about seeing photographs of men with various implements plunged into their bodily orifices.

“Surely, you’re not stereotyping?” I asked with as sophisticated a tone of sarcasm as I could muster. He was my professor, after all. I tried to sound cool and cynical and disinterested, but my insides were bubbling up. I had been in graduate school long enough to have sensed less-than-warm attitudes by many toward religious belief in general and Christianity in particular. I had not tried to hide my faith, but I had understood that it was best not to wear it on my sleeve either. I certainly had never confronted a professor about the bias I had seen both in and out of the classroom. Perhaps meeting in the professor’s home, in the relaxed comfort of the living room where we were casually circled, I felt a freedom I’m sure I’d have never felt in the classroom.

The room was dimly lit and I was grateful for this as I felt my face crimson. I don’t remember exactly my professor’s or my fellow students’ immediate reaction, but from the professor I think it was something along the lines of a terse admission and apology, followed by a quick change of subject.

What followed once the class was over is seared in my memory. On my way out, the professor stopped me at the door and offered a genuine, more profuse apology for what he acknowledged was a serious transgression against the liberal values he espoused. I had to respect him for both striving to be consistent with his own profession for tolerance and for admitting failure when he wasn’t. All the other students had left, and we spoke for about twenty minutes. A new understanding and mutual respect between us took root.

From this day on, my professor would often ask my view of topics in class, explaining to the others, respectfully, that he was particularly seeking my view as a Christian, thus paying more than lip service (unlike many of his peers) to the diversity and tolerance he valued. But many times my professor would talk to me more after class, sitting in the stifling space of his tiny office—it and hundreds others like it were part of the campus’s riot-proof architectural design, developed after the student protests of the sixties and epitomizing modernism’s cold, utilitarian, de-humanized aesthetics. We discussed Christianity and Christians, liberalism and liberals, conservatism and conservatives, free speech and John Milton—and the surprising role that a conservative, Puritan Christian had in developing one of the most cherished cornerstones of American freedom.

This was my introduction to Areopagitica.

(Adapted from Booked:Literature in the Soul of Me)

One additional thing I want to note in follow-up to this excerpt is that, as we will see, Milton was arguing for wide reading of theological, political, and doctrinal writings—the kinds of things that could get one imprisoned or burned at the stake in early Modern England. He wasn’t arguing for obscenity or age-inappropriate reading as we debate today. I don’t presume to say where Milton would land on these contemporary controversies. Nevertheless, his sound, biblical arguments formed the cornerstone of today’s freedom of speech in America.

"Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”3

***

BOOK NOTE:

The Mary We Forgot: What the Apostle to the Apostles Teaches the Church Today by Jennifer Powell McNutt is a newly released book that I was honored to endorse. The book is a scholarly but lively and accessible examination of the life of Mary Magdalene, told in the way only a historian and theologian who loves her material could. Jennifer brings to life not only the woman, but also the world in which she lived and the scriptures that record that world.

Thank you to reader Matt Franck for offering this note last week: Anyone seeking a hard copy of Areopagitica should consider the Liberty Fund edition, which also includes other political writings of Milton, and is a beautiful volume (sewn binding on a paperback!) at a great price: https://about.libertyfund.org/books/areopagitica-and-other-political-writings-of-john-milton/

You can access it online here.

It was John Cleland’s Fanny Hill: Or, Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, published in 1749.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. By Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002), 117.

I came across Areopagitica two days ago , at Blackwell’s, a bookshop I expect you know well dear Karen. It was one of the only sunny days Oxford had this autumn and I walked with my son across Magdalen bridge and right across town and I thought if you as I bought the book and how lovely it would be if you came and gave a talk there. (Areopagitica was hidden in the poetry section!!! Imagine!!!!)

As you know, I have read your memoir, and I especially appreciated this chapter. During my youth in a very controlling homeschool program, my father wouldn't have blacked out my assignments - he didn't appreciate Atwood, but he left my reading choices to me - but I knew parents in the same program who did black things out in books.

In a way, my parents giving me the freedom to choose for myself while the curriculum set impossibly high standards only increased the pressure for me. I would be in turmoil over whether I ought to read a book with a little swearing or look at a art book that probably had unclothed people. My struggles with religious scrupulosity didn't help. I am glad my parents gave me freedom, it is the program that was unnecessary torment.